The week we leave behind was undoubtedly a busy one in the Middle East. Big things are in motion. After almost a year former Lebanese Prime Minister Sa‘ad al-Ḥarīrī managed to climb back to power and seemingly end the crisis, which he himself started with his resignation.

Big things are in motion around Syria as well, as reports have claimed that Washington tried to reach out to Damascus only be rejected. Yet something is clearly going on, as not only the Turkish forces started to give up some of their so-called “observation” military posts – a thing they vowed never to do – but recently even Qatar reopened direct flights do Damascus. Even though Doha was one of the big orchestrators of the war on Syrian, which started in 2011. Clearly, the repositioning between the camps is in motion, while the block around the Emirates dedicates its full attention to the American elections and try to gain the most possible even before it.

In the midst of all these events came the sensational announcement by Trump on Monday, 19 of October that Sudan is about to pay $335 million compensation to Washington, for in exchange it will be removed from the list of countries supporting terrorism. That alone is a clear indication that Khartoum is finally ready to surrender to pressure and normalize relations with Israel. And Trump left no doubt about that. That was soon followed by the visit of an Israeli delegation into Sudan to discuss the details. Then on Friday blew the bomb, Trump announced that Sudan agreed to the normalization. Though certain detail leaves some doubt about that.

Things were heading this way steadily, ever since the infamous meeting between Netanyahu and Sudanese leader al-Burhān in Uganda this February. The pressure only grew since the famous normalization between Tel Aviv and Abū Zabī, to which the Emiratis try to enlist ever more Arab states.

The picture, however, is not that clear just yet. Sudanese officials still heavily deny that two matters, the removal from the terror list and the normalization are connected and we still don’t see any open statement from the Sudanese leaders themselves clarifying the matter. So far all news and evaluation are coming from Western and Israeli sources, so we don’t really see clear about the Sudanese position. While since Friday massive protests broke out in reaction to the announcement and the major parties started to pressure the government to retract from this decision.

So, is Sudan the next one to jump on the bandwagon? Or the leaders of Khartoum are playing a very dangerous gamble winning time, waiting for the new boss in the White House?

What happened since al-Bašīr left?

Ever since the former Sudanese leadership lead by ‘Umar al-Bašīr was overthrown in April 2019 the country is steadily drifting, though the Emirati-Saudi influence becomes ever more dominant. Soon after the coup both the Parliament and most major political institutions were dissolved and in their stead, the army took control by the Sudanese Transitional Sovereignty Council. This is lead by General ‘Abd al-Fattāḥ al-Burhān. Al-Burhān based his rule so far on the military and promised this transitional rule would not last longer than two years maximum, yet his position is very fragile for a number of reasons.

First of all, because al-Bašīr himself came to power decades ago in a similarly staged military coup, and he also vowed to step down after matters are resolved, yet managed stay for three full decades. This notion is only more alarming by the fact the firmest supporters of this new leadership after the Emirates – the state being really at the control – in Egypt. And here another ‘Abd al-Fattāḥ, President as-Sīsī made an almost identical carrier overthrowing a Muslim Brotherhood government as the Chief of Staff. He also promised to restore democracy and leave office after a short interim period, yet after more than seven years he is clearly about to stay for long. Therefore it is not a coincidence that the protests, which ultimately undermined al-Bašīr did not stop after the coup and grew only more fierce with the prospect that in the end, the army would still stay in power. That leads to violent clashes and a brutal crackdown in June 2019, less than two months after al-Bašīr’s ouster.

The second problem is that though al-Burhān has most of the military behind him with support from the Emirates and Egypt, he cannot be absolutely sure about the military. The officers corps, within which he was not the most senior member and had a relatively negative reputation being part of the Dārfūr and South Sudan wars, are very divided. Many would rather see either a member, who has a past less tied to al-Bašīr, or a more nationalist character. Which made him result to recruit strong allies.

And that is his third problem. Al-Burhān might be serious to hand over power eventually, or might not, that is hard to know, but whatever agenda he has to make things better, he heavily forced to compromise. On the one hand, on the internal front, and on the other by pressures of his foreign supporters, who see a very strong asset in Sudan.

To gain more reliable forces, but also to prevent a powerful rival from overthrowing him al-Burhān made a deal with one of the most infamous characters in Sudan, General Muḥammad Ḥamdān Daqalū, otherwise known by his nickname as Ḥamīdī. Daqalū, who is some 15 years younger than al-Burhān with a tribal ancestry and is much more in touch with the field soldiers gained a fierce reputation during the war in Dārfūr. Daqalū was born in Chad to a strong tribal federation and never had a real education dropping from school at the age of 13. With his family, he moved to Dārfūr and was engaged in a number of questionable trade businesses, mostly as a tough man, or arranging protection. Being a rough man as he is, under the directives of President al-Bašīr at that time he formed the infamous Ğanğawīd militia, which was primarily responsible for squashing the rebellion in the province and committing the most brutal offenses for the government. His unit was transformed into the Rapid Support Forces, in which his younger brother is his first deputy and which was a useful asset for the previous president. By his activities, he managed to significant interest in Sudan’s mines and became the richest man in the country.

Daqalū belonged to the more loyal echelons of the al-Bašīr’s rule, yet he as well switched sides and became the backbone al-Burhān’s rule, making him his deputy both in the army and the Transitional Sovereignty Council. He is of a much stronger character with a fearsome tribal paramilitary militia behind him, who enjoys an excellent connection with the Emirates. So much so that in August 2019, when the Emirates was desperately tried to force Egypt to lend more support to General Ḥaftar in Libya but reached no result it contacted Ḥamīdtī. He soon sent some 4000 members of the Rapid Support Force to Libya, where this unit became of the most effective strike forces of Ḥaftar. In light of this power and connection, Daqalū is a very strong asset, but also a liability for al-Burhān. In part because he is so powerful, but also because many in the army fear this unit and dissent might grow in time.

Ḥamīdtī is primarily interested in internal matters and his own influence, less about regional politics, which made him be an ideal candidate for the Emirates to become its tool in the quest to push Sudan for normalization. And with much success, as he recently became the most outspoken supporter for the normalization.

Partially as a counterweight, but also as a cover for this lightly covered military governmental-Burhān set up a new government and enlisted ‘Abd Allah Ḥamdūk to lead it. Ḥamdūk, a carrier diplomat and a capable economist finished his studies in Manchester and once worked for the Ministry Finance and Economic Planning. His reputation is one of the cleanest, as he is known to be progressive and during the last years al-Bašīr was abroad working as Deputy Executive Secretary of the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA). He was never a party member and a good diplomat, therefore in August 2019 al-Burhān appointed him to be the Prime

Minister in the transitional period.

Since then Ḥamdūk did serve as a counterweight to Daqalū trying to arrange a smooth transition to civilian control. In regional politics, however, he is one of the skeptics when it comes to relations with the Emirates and Egypt. It was mostly due to his efforts that the government until this Friday managed to evade the normalization process, yet his civilian power base in this primarily military lead government might have been insufficient. Allegedly during Pompeo’s visit to Sudan in August, it was Ḥamdūk, who managed to foil a deal, which would have forced Sudan to join the normalization, just like Bahrain did. At that time Khartoum said that this matter should be postponed to after the elections when the new government could decide on this. Which was a clear attempt to evade this path.

So it can be understood that when the matter of normalization is discussed al-Burhān is not in an enviable position. On one hand, the population is clearly against it, even resent much of the connections to the Gulf. Yet on the other hand his authority rests upon the little support he has and his much more compromising rival is ready to take his place if that is needed. That is one of the reasons why the government was practically incapacitated since the coup. Many of the economic problems could not even be tackled, sporadic unrest sometimes renders entire regions out of control and a few weeks ago the government was helpless when the worst floods in decades have crippled the country. Even more symptomatic that while the world struggles with the Corona pandemic in September Sudan experienced a polio epidemic as a result of the WHO’s vaccination campaign. Of course WHO deflected the claim on rare mutation and poor sanitation, nonetheless the campaign was stopped and suspicions arose about the vaccines used.

The price of Sudan

Though the conditions seem very grim today, Sudan is in fact far from being poor, or underdeveloped, as popular imagination holds it about most African countries. The country has excellent agricultural potential, rich in oil, gas, gold, and a number of other ores, and is situated in an ideal place along the Red Sea for international trade. So there seems to be a way out.

Yet the economy to be launched again and to be efficiently reconstructed, to find away to the growing spiral of economic crisis Sudan needs funds. Investment and trade possibilities, which are hard to obtain, as the country is under American sanctions being on the list of countries supporting terrorism. Ḥamdūk’s biggest aim, both politically to secure his government and economically was to achieve Sudan’s removal from the list. That is what has started this week, but regardless of all the efforts Washington – just like Riyadh and Abū Zabī – tie this to the normalization with Israel. A matter Khartoum desperately wanted to avoid.

Yet it is clear that in spite of all the pressures and tempting offers Sudan does not wish relations with Israel in any way. It is only yielding under pressure. So the question is fitting, what is the price of Sudan for those who push for normalization? Why does Sudan matter?

For all parties involved it we get a very different answer. For the US itself, Sudan is not overwhelmingly important. The most significant matter, which was suggested in the news that Washington wants control over the Sudanese Red Sea ports and prohibit Chinese companies investing in Sudan. Given the influence Beijing already has there, the Sudanese need for assets and the overall race for influence in Africa between China and the US Sudan can be an important piece in the puzzle. Yet this matter can be agreed upon if the need for funds is met. And this can be solved without any Israeli involvement. For Trump, Sudan has no specific importance at all, but so close to the elections he needs to secure favors for the lobby groups. So for him, whether it is Sudan, Saudi Arabia, or Mauritania that is not important, only that he can announce more gains. That is probably how the last-minute idea that Sudan has to pay indemnity to Washington came up, as Trumps needs to show that he brought money.

For Riyadh specifically, Sudan is important, though not indispensable. Sudan provides – and since the coup, this role even grew – troops to the war efforts in Yemen. Which is not going well for the kingdom. On 15 October a major prisoners exchange took place with Sana’a showing that Riyadh cannot disregard the al-Ḥūtī government anymore. In the south of Yemen, the Emirates is carving up its own possession, meaning soon the Saudis will be left alone in this war with no direct international, Gulf, or local support. In this regard the Sudanese presence is crucial, to keep Saudi casualties down, and to have some leverage against the Emiratis. But apart from that specific folder Sudan is not a specifically important target for the Saudi economy or strategic thinking. Much more so for Saudi Crown Prince Muḥammad ibn Salmān. The equation is very simple and resembles that of Trump. Given the still growing resistance to his takeover upon the possibly close death of his father, regardless of all the purges he made, he desperately needs American and Emirati support, no matter what. And to secure favor he does the most to help the normalization, as being a hero here might secure his succession. His efforts are perfectly shown in the fact that recently he has been chosen by one of the “Friends of Israel” award, by a Jerusalem-based pseudo-Christian group, and on the annual summit Netanyahu, the Israeli president, and the American ambassador were all present. Recently Israeli sources named him the biggest supporter of the normalization in the Saudi state, who was it up to him would have already made Riyadh join the process. He is so keen to show the result that he arranged for Saudi to pay the requested $335 million in Sudan’s stead to secure the deal. The Emirates count on Sudan in the very same way. A military asset in Yemen, Libya, and possibly other parts of the world if needed, and another trophy in the normalization to cement the strategic partnership with Israel.

But what does Sudan mean for Israel? According to Netanyahu and most Israeli officials practically nothing. Yet this is clearly wrong, given the attention, their media dedicates to the matter. Since the announcement of the normalization on Friday Israeli interests put articles everywhere explaining how immensely important this step is, even more, that with the Emirates. There is a very important moral segment to it, as Khartoum hosted the Arab League summit in 1967 accepting the principle of “Three No’s” forbidding peace, individual negotiations, and recognition for Israel in response to the war the Jewish state started that year. Having Khartoum to join a club breaking this principle is a moral victory. All other details are less clear, and even these celebrating articles admit that there is nothing clear about the settlement. If indeed there will be one. Nor embassy, not even diplomatic or economic relations. One reason for that is the lack of clarity and the fragile state of the deal in Sudan, but the other is that Sudan is part of a bigger plan of containment.

Regardless of the peace treaty Israel always holds Egypt as the most important Arab state, which has to be pinned down. This process started long ago, and as Sudan was important, thought hardy accessible country Tel Aviv supported militarily the insurgency in South Sudan until that state was created. That has become a bulwark of Israeli interests against Khartoum. Now, if Khartoum falls, it can be turned – with intensive Emirati help – into a major operation center, keeping Egypt in the bay even more. Sudan was an important transit port of support for Palestinians, and by now the Israeli openly admit that they committed several atrocities against Sudan for that. Now this transit route can also be sealed, and a direct way can be arranged to inner Africa, where Israeli economic interests are already very active. So the fall of Sudan is indeed a very big step for Israel. It means a big supporter for the Palestinians lost, and a major operation hub between Yemen and Egypt can be won.

At the end of a long process

Speculation about Sudan’s possible normalization actually predates the Emirati deal. The first open sign was al-Burhān’s meeting with Netanyahu in Uganda in 2020 February. After which Sudan did enough gesture to allow free passage for Israeli civilian planes. Talks, however, did not really progress until summer, by which time the major demands have become clear.

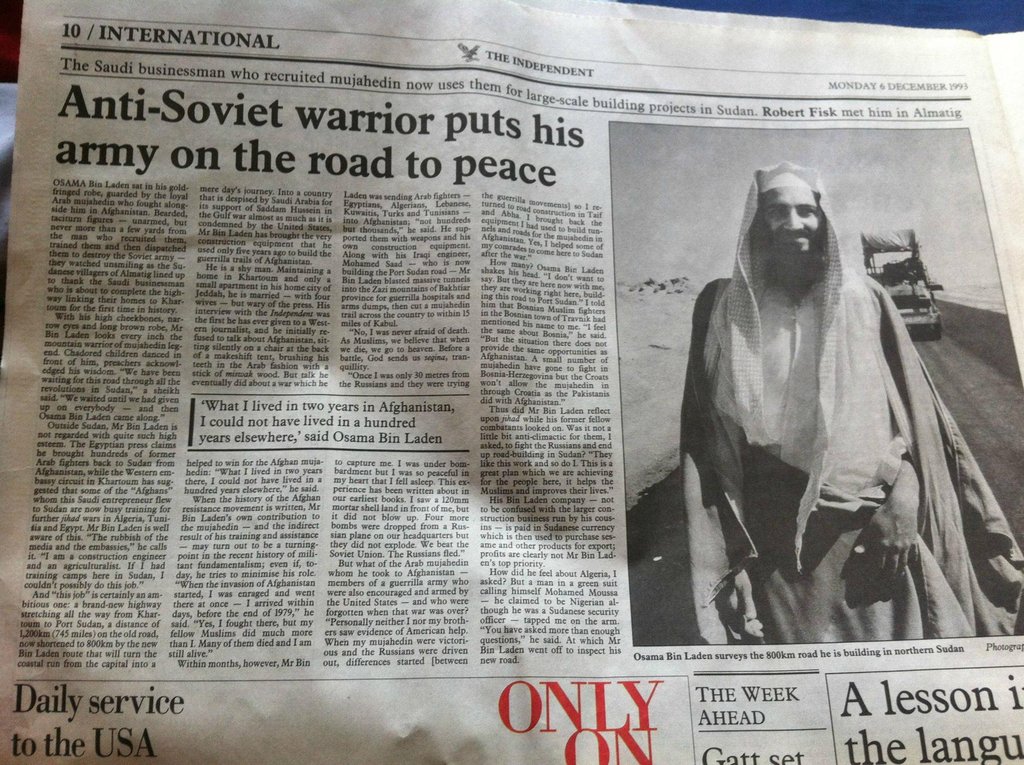

Sudan wanted to be taken off the list of terrorism-sponsoring countries and wanted the sanctions to be removed. It wanted access to IMF credit funds, to which getting off the terror list was a condition. And the government wanted immediate cash transfers. Though sources differ on the amount, it was somewhere between $3-10 billion. Even if that is toned down, clearly paying the $335 million to Washington would not have been a loss, even without Riyadh paying it. On the other hand, Washington wanted normalization as a precondition for anything. Above that, it wanted access to the Red Sea ports, military bases in the south, prohibiting Chinese companies to operate here. Only in the last minute, Trump came up with the $335 million compensation demand, for terrorist attacks in the ‘90 vaguely connected – a never proven – to Sudan, and for Usāma bin Lādin’s stay in the country, though at that time the Western press celebrated him for that.

Given all these matters aside from the normalization are not even talked about, we can either assume that these demands were all agreed to mutually, or were later dropped. Only time will tell.

Things really got into motion after the Emirati deal with Israel, when everyone was guessing which Arab state is the next. Just like now, presuming Sudan’s matter is done. But at that time Khartoum evaded the pressure with a good excuse. As an alternative, the US asked Sudan to send its – an American citizen – Minister of Justice to the Abraham Accords ceremony in Washington, but the Sudanese government, especially Ḥamdūk resisted. But there was no question that the matter of terror list and the normalization are inseparable, no matter what Ḥamdūk wants. Al-Burhān was the first one to buckle, as in late September he started negotiations directly. Then it was Ḥamīdtī’s turn, who in a television interview in early October claimed that the “people are over this” and practically gave a green light. With this Ḥamdūk was practically left alone.

Then came the announcement on 19 October by Trump that Sudan had agreed to pay the $335 million, for which it will be off the terror list and normalization will soon follow. Expectations were high, and the first groundbreaking step came on Wednesday 21 October, when an Israeli delegation accompanied by American officials arrived in Khartoum. Which was met with massive protests. Then on 23 October Sudan – from Saudi money – made the transfer, Trump signed the decree to remove Sudan from the list, and normalization was announced. Interesting only by American and Israeli sources, but claiming that both al-Burhān and Ḥamdūk took part in the conversation. Interestingly there is nothing signed yet, just strong and undenied statements.

What can be deducted from that is that both camps tried, and possibly still try to outmaneuver the other. Sudan wanted to get off the list, but not to normalize. Washington was willing to take Sudan off – thus showing the seriousness of such a list -, but only after Sudan normalized with Israel. That caused this confusing sequence when both parties made steps as guarantees. Because Sudan feared that Washington would not give concessions until further demands are met, while the American sensed that after the removal the Sudanese might backtrack. And that is still a possible scenario, as the Congress hasn’t approved the motion yet – might not even do before the elections -, while Sudan says that all that happened was only an agreement about normalization, which as to be approved by the parliament, which is not even elected yet. So the game is technically not over yet, and it can still change. Either by the American election or by reactions in Sudan.

Is it over?

The tone in which the Americans and the Israelis, both the media and Netanyahu himself talk now is very convincing. It seems very clear that the question is over. The Israeli delegation visiting Khartoum and the allegedly signed deal leaves little doubt. Thought this tone was constant for more than two months and so far only managed to force occupied Bahrain into the deal.

Several things are curious and might give insight that regardless of the official announcement there in fact a very fierce struggle within the Sudanese political forces. So the game might just not be over. It is true that Trump has announced that Sudan will agree to the normalization, but we haven’t heard anything clear and final from the Sudanese government. Netanyahu is celebrating, but he was wrong about the “series of Arab countries standing in line” too. And he was proved to be lying even by Washington when he said that the Emirates is not getting anything in exchange and there was no deal about selling F-35 jets to Abū Zabī.

The massive protests after the Israeli visit show that the population is against the decision and if the government agrees it plays with fire. Especially that it is very hard to know how many would oppose this path in the army. It is also very telling that after the visit the Israelis shared no details. On 23 October, even before the announcement the Party of the Sudanese Nation – one of the biggest parties – threatened to withdraw its support from the government in case it normalizes, and reminded that the government has no such prerogatives, given its interim nature. A day after the official announcement the Sudanese “Ba‘at” Parts did revoke its support, being just the first one. And in the meantime, there are massive protests in Khartoum for the second day.

Indeed there can be very little doubt that there is huge pressure on Sudan and that it is buckling. It is also clear that Sudan does want better relations with the West and is willing to make concessions, even in the expanse of its position about Palestine, but not to the level of making pacts with Israel. The resistance is clear. So it might just be that the current leadership with little concessions going the slowest possible to gain precious time until the American elections. If Biden wins he might not be aggressive about this project and let Sudan dodge the matter. But even if Trump wins, he might be less in need of such gestures and let the issue go. Either way, time is gold for Sudan now, especially for the civilian government.

The resistance, however, especially by the streets is a warning sign. The current government might not live long enough to fulfill these promises. Also, the case of Mauritania should be remembered, which once made a similar pact under pressure. Only to backtrack from it a decade later. Therefore whatever the following days bring, the game for Sudan is not over.