It is clear that the war in Ukraine is something which hasn’t been seen since probably the Cuban missile crisis. It has the potential to ignite a global war, which in many aspects could be argued that has started already, and with all its aspects it has fearsome prospects. So far the NATO backed off from directly get itself involved in the war, so the potential of an all out nuclear war is getting farther every day. However, because the crisis is not about to be resolved fast the economic consequences are growing, potentially ushering in an age of a new Cold War.

Because of this the world is getting polarized ever more. The Ukrainian crisis is only the catalyst in this process, as the divisions along the major economic interests for the next age were visible long ago. One living in the West, or having access to most just Western media outlets, which are now in the name of freedom blocking out all access to any news contrary to the mainstream narrative, could assume the Russia is isolated. However, the equation is far from being so clear globally, as a quite substantial number of globally impactful states, like China, India, Pakistan, Indonesia, Brazil, or even practically the whole Middle East refused to join the economic sanctions against Russia. Some even took a stance directly supporting Russia. This is an important question, because it reflects whether the so called Western is really isolating Russia, or itself on the global scale with its sanctions.

When assessing the global layout, the role of the Persian Gulf is particularly important. Both for the direct short-term, and the less direct long-term deliberations. On the direct level, the Gulf could be the immediate substitute for the Russian energy resources – primarily oil and gas -, which the the US aims to use as a leverage against Russia. But in the long term, their behavior now, in such a sensitive time when their bargaining potential has grown immensely, reflects their thinking for the future. Which is a crucial matter, as the American control over the Middle East is receding, while that of the rivals is growing. The overall sign that almost no Arab state took positions clearly with Washington, much more with Russia is a warning sign itself. But which way the Gulf is leaning now?

Why the Gulf is important?

First all of all we have to understand that the role of the Persian Gulf, both for this current standoff between Washington and Moscow, and both for the future of this now unrolling economic global war is immensely important. Indeed the Gulf states one by one, with the possible exception of Iran, have little weight on their own in this crisis. The six Arab states of the Gulf, the members of the GCC could mount more pressure either way, or could exploit the situation more for their own benefit, but this group is still deeply divided and hasn’t recuperated from the four years long economic war against Qatar. Having stated that, the Gulf is still extremely important now, because it has the potential to equal up the loss of Russian energy resources in the European, and overall in the global market.

Out of the top ten oil producers in the world, three are GCC members, and two are also in the close vicinity. In 2020 Saudi Arabia was the second, the Emirates the seventh, and Kuwait the tenth, while Iran also in the Gulf – and still heavily under sanctions – was the ninth, and Iraq the sixth. Together they produced 26% of the total global output that year, which hasn’t really changed since. Given the US is the biggest producer with some 20% and Russia alone – not counting such close allies as Azerbaijan, or Kazakhstan – 11%, it easy to see that it is not a secondary question where the Gulf stands on the current crisis.

As for the natural gas, at the same year the out of the top ten producers three were Gulf countries, and two from the GCC. Also interesting the tenth was Algeria, a country also intimately close to Moscow. While once again the US was the biggest by far, Russia was the second and Iran the third, while Qatar was the fifth and Saudi Arabia the eighth.

It should also be noted that the US is not only the biggest producer for both of these commodities, but also the biggest user. While the domestic needs of the Gulf countries, especially that of Iran move it toward using more nuclear energy, are far smaller than their output. Meaning their potential to influence the global markets are far superior to that of the Americans’.

Pouring in more energy resources to the global market they could potentially calm the situation and make the sanctions against Russia way more effective and feasible. Since even the American oil companies struggle to fulfill Biden’s dream sanctions, while a number of European states are now simply not in the situation to simply just block out the Russian supply. Given its potential and relative closeness to Europe, the Gulf states could play a significant role in this game. Given they want to. But do they?

Saudi Arabia and the Emirates

Traditionally these are closest American allies in the Gulf, and with the biggest potential. So it is only natural the Biden gambled on their complicity about the anti-Russian sanctions.

Now doubt, as the American oil and gas production is growing and needs to find markets, a major reason from the current crisis with Russia is an economic war, when Washington aims to squeeze out the Russian energy supplies from the European markets to make way for its own products. It is true that the American output even is insufficient even in the long to completely replace the Russian supply that is not Washington’s problem. While the contradiction is obvious, the White House could hope for putting pressure on it’s allies to fulfill the needs, and even until than increase the output to calm the markets and prevent a massive price spike. In that, especially after it became evident that even many close European allies are incapable to replacing Russian energy supplies and therefore reluctant to join the sanctions, Saudi Arabia and the Emirates were very obvious choices. But here came the surprise.

It was published first by the Wall Street Journal that both the de facto rulers of the Saudi Arabia and the Emirates, Crown Prince Muḥammad ibn Salmān and Crown Prince Muḥammad ibn Zāyid refused (Magyar) to hold a telephone conversation with Biden. Allegedly, because they knew full well that Biden wants to put pressure on them to increase oil production to compensate the loss of Russian oil in the markets.

The American newspaper reasoned that both counties have serious reasons to be on uneasy terms with Washington, and while they would be willing to join the sanctions regime, they have a list of demands first to be fulfilled. Meaning they have no problem with this project, only they increase the political price for it from Washington. One matter being an increased support in the war in Yemen and the other is stopping, or significantly toning down the level of the Iranian nuclear deal. Added to that, Saudi Crown Prince Muḥammad ibn Salmān also wants guarantees that he won’t be put on trial for a number of legal cases in the U.S. He also has a personal reason to dislike Biden, as after the excellent ties with Trump, Biden did all he could to downplay him and push for Ibn Salmān’s replacement with a more suitable next ruler of the kingdom.

However, we should not forget where these alleged informations are coming from. Surely there are a number of American circles dissatisfied with Biden and blame him for the worsening relations with all Gulf states in recent times. But this trend did not start with Biden at all.

The first major sign that something is drastically changing in the Gulf’s approach came out in November 2021, when it was uncovered that China while upgrading a port near Abū Zabī started building a secret naval base. It was halted after pressure from Washington. The Emirati leadership officially claimed that had no knowledge of such naval base being in preparation, it is highly unlikely. Thus suggesting that the Emirati-Chinese relations are already in a very developed stage.

It is true that both countries are dissatisfied with the Biden administration’s handling of the Yemeni war, as Biden took the al-Ḥūtīs off the list of terrorist entities, and scaled down – not completely cutting, as claimed – the support for the war effort here. It is fairly well understood that Washington is the key motivator for a number of reasons in the war in Yemen. Both of these states have huge dilemma how to end their involvement in Yemen, but both of them developed ways for that apart from the U.S. Both of them reached out to Iran to seek for mediation, and while it hasn’t yielded great results yet, these negotiations are promising. The visit by the most prominent security leader of the Emirates Ṭaḥnūn ibn Zāyid to Tehran in December 2021 was the first major step in this direction, while the latest remarks from Riyadh about the negotiations with Iran also underlines the importance of this trajectory. Also, the Emirates has already invited Israel to its future plans in Yemen, also securing that even in the worst case some of the spoils of war can be salvaged.

It is also true that Saudi Arabia and the Emirates in early 2022 increased their military activity with some level of success in Yemen, the backlash on Dubai and the number of Saudi airports by the Yemeni forces put a holt for the military approach, at least for a while. In short, while Washington could offer increased support in Yemen, its behavior in recent years and the failure to give sufficient aid to the Emirates after the Yemenis successfully hit Dubai proved that simply relying on the Americans is no longer a viable option. Simply put, the Biden administration has already lost this chance.

It is significant that while they refused to talk to Biden, a week before both Ibn Zāyid and Ibn Salmān talked with President Putin. And while both offered to mediate in the crisis with Ukraine, the most important part of their negotiations was that both states pledged to commit to the OPEC+ plan about the projected output. Meaning that even before Biden wanted to asked them, early on in the crisis both Saudi Arabia and the Emirates clearly stated that they will not increase oil production to balance the loss of Russian oil. Meaning they will not take part in the sanctions project. They took a stance with Russia. Which might be surprising, but there are reasons for that way beyond some personal deliberations. The fact that shortly after refusing Biden Ibn Salmān held a meeting with Egyptian President as-Sīsī in Riyadh, where once again energy cooperation was high on the agenda, it is clear that most Arab states, especially those which are important in the oil and gas supply are not willing to commit to the sanctions. And the leading Gulf states are even encouraging this approach.

Qatar

While Qatar is not a major oil supplier, its role might even overshadows that of Riyadh and and Abū Zabī. As we saw, Qatar is one of the largest natural gas producer and exporter in the world. And if the European states struggle to substitute the Russian oil, they, especially the Eastern Central European ones, otherwise key allies of Washington have an even harder time to give up Russian gas. Qatar is not only a major supplier, but a highly developed one, which in theory could substitute the loss of Russian gas even without existing pipelines with liquified gas. At least partially. The increased American supply added to that could mean at least partial solution, but for that Doha would have to increase its supply significantly.

But Qatar had an even firmer refusal for Washington. Only two days before the war in Ukraine began, on 22 February Qatar hosted the meeting of the top oil production countries (GECF), including Russia, which stated that nor Qatar, nor any other state can replace Russian gas with liquefied gas. Qatar was approached even before the war, in January, so the later remarks and the fact that Doha is still adamant about this position – regardless of the technical difficulties – shows that Qatar is also reluctant to team up with Washington against Russia.

Also interesting that to the very personal invitation of the Qatari Emir Iranian President Ra’īsī took part in this GECF meeting and on the side had extensive negotiations with his Qatari host. Beyond bilateral ties and other diplomatic niceties the two key issues were the nuclear negotiations and energy cooperation.

Qatar also has a number of reasons not to rush helping out Washington. The long years of the blockade against it by Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Egypt and the Emirate, which only ended a little more than a year ago put a very heavy burden on the American-Qatari relations. Because from the Qatari point of view Trump was clearly siding the blockade, or at least did nothing against it. And since Biden took office he did nothing to mend the wounds. Which rightly makes Doha feel neglected.

Once again we can find a very strange pattern that otherwise very harsh rivals are on the exactly same course about Russia and the energy related sanctions. The other strange constellation is that the otherwise less then friendly India and Pakistan are on the same page. Of course, Qatar could reason that it is way to small to replace all the massive Russian supplies alone. This is indeed the course the Qatari diplomacy took, which sound reasonable. But hosting the most significant gas forum at a time when war with Russia was well on the horizon suggests a very different explanation.

Oman

When it comes to Oman, we could easily disregard it as a major player in such deliberations. While Oman’s economy as also largely built on oil export, Muscat is not an overall major global player and almost half of its sales are heading to Japan.

The real reason why Oman is important in this assessment is because the Sultanate is the traditional mediator and diplomatic hub of the Gulf always trying to ease conflicts. So in theory could be an ideal launch point for the American diplomacy to convince the Gulf for a larger output.

Also, in recent years Oman had a number of diplomatic conflicts with the Emirates, and was deeply concern about the war in Yemen. So it could be counted to on to argue for a bigger Gulf role in the sanctions.

But we find nothing of this. The first official reaction to the crisis in Ukraine by Sultan Haytam only came on 3 March. In that the Omani ruler expressed his deepest concern, but nothing beyond that. Meaning he did not condemn any sides and had no intention to join the sanctions. And while Oman takes part in all international mediation efforts, it refrains from taking sides.

It is important to note that Oman struggles with a significant budget deficit for years, and as was assessed by Omani circles at the very beginning of the war, while the war is worrying, overall it has very positive affects on the Gulf economy. With skyrocketing oil prices the Gulf economy still ravaged by the Covid pandemic, will soon recover, without increasing the output. And that assessment is probably true to all Gulf states, somewhat explaining their motives.

It is also important to note that Omani Foreign Minister Badr ibn Ḥamad al-Būsa‘īdī payed a visit to Iran on 23 February, delivering a personal message from the Sultan to the Iranian President urging stronger bilateral ties.

Kuwait and Bahrain

Kuwait and Bahrain, while also significant oil producing countries, especially Kuwait, play very little role in the Gulf policy towards the Ukrainian crisis. Yet to make the picture clear, we have to assess them.

Kuwait has a significant internal problem, as the Emir Nawāf aṣ-Ṣabāḥ aged 84, who only took the throne in September 2020 is very ill and in November 2021 delegated most of his powers to his Crown Prince. Crown Prince Miš‘al aṣ-Ṣabāḥ is also in a late age of 81, and so far played a very limited role in the state’s administration. The small state also suffers from a permanent internal dispute, and recently key members of the government resigned. Under such conditions the decision makers in Kuwait are way more entangled with internal problems than to be able to conduct separate foreign policy. That is why Kuwait also refrained from taking any sides, while enjoys the benefits of the war’s economic results for its economy.

Bahrain is in a very similar position, though not caused by internal conflicts. It has recently became a testing ground for the developing Gulf-Israeli ties. Since these matters are way more crucial for Manama, it is on the one hand largely indifferent to the Ukrainian crisis, and on the other facing pressure for all its policies from Riyadh and Abū Zabī. Bahrain is truly one of the most significant American position in the Gulf and its now rapidly developing ties with Israel, which took a firm stance against Russia. This could suggest also taking sides against Moscow. But Bahrain is in no position to contradict its neighbors. Thus it would be the only Gulf states to join the sanctions, which is not even in its best interest.

Is Iran the biggest winner, or biggest loser?

Now many American analysts suggest that the biggest loser of the Ukrainian war in the Middle East is Iran. Not particularly for its clear stance with Russia blaming Washington for what happened. That fits well with the traditional political tone of Tehran. Much more because with the war the center of all diplomatic attention now turned away from the Vienna nuclear talks. Practically Iran was put on hold with this critical matter. And now even its traditional support by the Russia and China has little weight in these negotiations.

But is that really true? In fact, while Russia’s role in the possible nuclear deal has indeed fell back, China’s has not. On the other hand, as the West is pushing for sanctions against Russia it is in the verge of creating an alternative camp not seen since the Cold War. In that China and Russia are essential players, and many other key global states, like India, Pakistan, Brazil, Egypt and the Gulf are not against it. This gives Iran a bargaining chip that refusing a deal now will mean Iran turning permanently towards that camp, which is waiting for it with open arms. Iran rejoining the global energy supply on the large scale could be an alternative to Russia, at least in some levels.

So by now it is just as much a Western interest to lift most sanctions against Iran than it is for Tehran. Also, as the Gulf is also not joining the sanctions, it is now improving its relations with its neighbors. And there is a positive reception for it.

Though the nuclear negotiations indeed got out of the center of attention, it actually makes it easier for every party to disregard objection, practically by now only coming from Israel. The world is more concerned about Ukraine now, which plays to the Iranians hand. And masters of diplomacy as they are, they know how to exploit it.

And its not just about the Gulf

Assessing the Gulf is immensely important given its weight in the global economy, especially in the field of energy supply. Yet it should be noted that overall in the Middle East and in the Islamic world there is no great enthusiasm to side with America now and to join the sanctions. The Gulf is not acting out of context here, or going against some trend. Quite the opposite, in an unusual fashion, it joins and in some ways stimulates it. Practically the only Arabic state to support the American position was the crisis wrecked Lebanon, which already caused huge controversies.

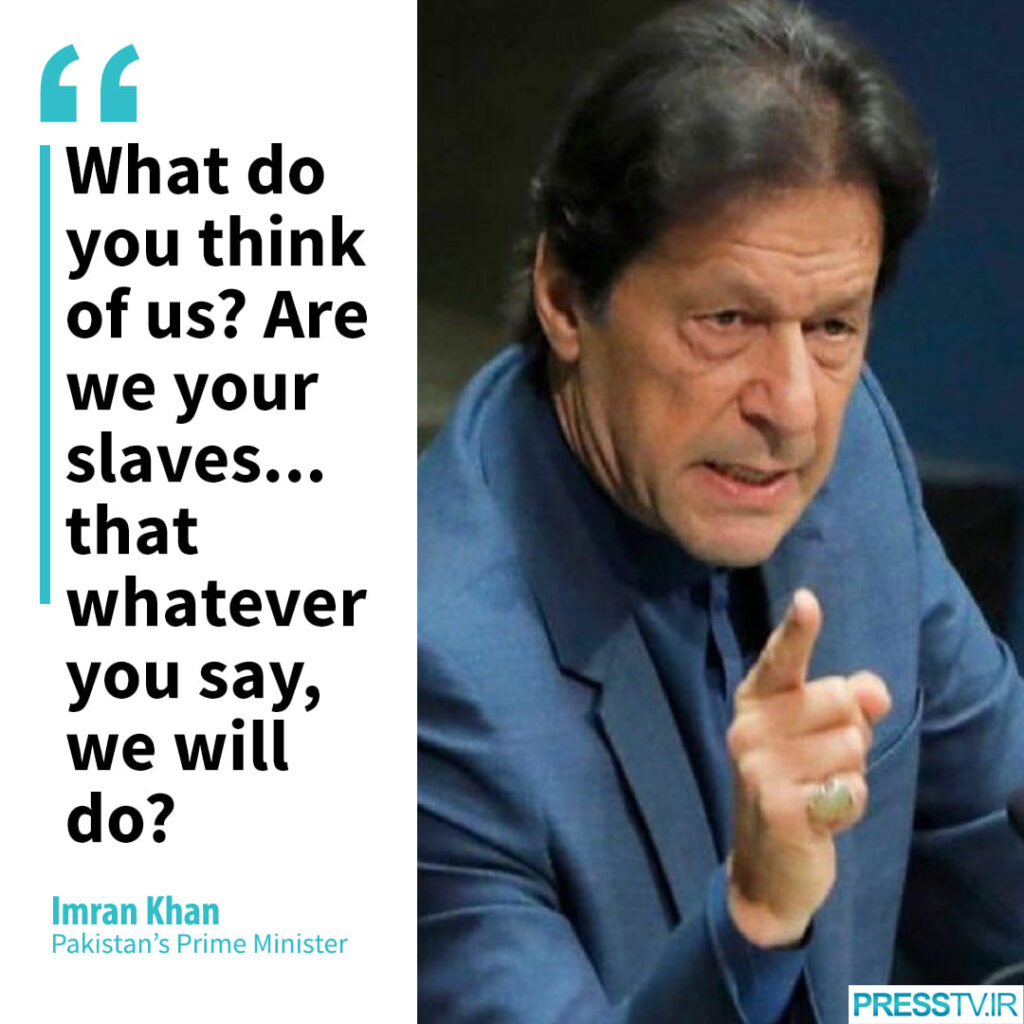

We have already discussed the position of some countries in the region, like Syria, Azerbaijan, or Algeria all taking sides with Russia on different levels. Pakistan, which is on less than favorable terms with Russia traditionally also on the eve of the current war held high level meetings in Moscow and aimed for more intense energy cooperation. Even more, when in the U.N. General Assembly Pakistan was pressured by America and a number of European state to condemn Russia and join the sanctions Pakistani Prime Minister ‘Imrān Hān lashed out in an unprecedented fashion.

But even more interesting that several states, which are just as deep in crisis as Lebanon and facing foreign pressures also chose not stay neutral, but to side with Russia. One interesting example is Sudan, where after the transitional government practically collapsed protests are going on almost daily. On the eve of the Ukrainian war, on 23 February Khartoum sent a high level delegation to Moscow asking for cooperation, practically Russian support against the massive American pressure. Even more, on 3 March the second man of the country General Muḥammad Ḥamdān Daqalū said that “there is no objection having a Russian military base along the Red Sea”, as this “poses no security threat to the security of Sudan”. Surely Washington would differ on this.

Meaning that even after the Russian operation in Ukraine started and still in progress a country still asks for Russian military presence. A country, which was forced into an agreement with Israel and under immense American pressures.

There is an overall trend all over the Middle East. Some are calculating that economic interests are simply not supporting the idea of joining the sanctions against Russia. But for many Russia is no longer viewed as an ideology driven and fearsome Soviet entity, but a viable alternative to America. Which in the last three decades at least had a huge destructive role in the region.

New winds are blowing

As for the Gulf, even if the opinion centers in the West try to obscure this, there are a number of reasons not to join the economic war on Russia. Financial interests are just one of them, as they have no incentive to increase production at the time of prices skyrocketing, only to limit their own income.

There are of course personal motivations for a form of payback, as we saw both with Saudi Arabia and the Emirates on the one hand, and Qatar on the other.

But there is an even bigger reason for that. These so far staunch American allies are testing the limits. How far they can go against Washington’s will. They surely don’t believe that they could break away from American guidance completely, nor that Russia, or China could replace it. At least not yet. But the world is moving in this trajectory.

That is why they are all looking for alternatives. With Israel before, which is still not a finished project, but also rapidly mending fences with Iran at the eve of a new nuclear deal. Noting that all major Gulf players had high level meeting, or contacts with Tehran since the current crisis started.

Time will tell how far they would go. But their refusal to the American demands, symbolic as it may seem, is showing that new winds are blowing in the Gulf.