Yemen is in turmoil since the so-called “Arab Spring”. After the long reign of President ‘Alī ‘Abd Allah Ṣāliḥ ended following massive protests and huge pressure from the neighbors and a few years of fragile peace came to rule the state, which eventually broke down in 2014.

Because of the weak central government discontent grew, which gave way to all decentralizing forces. The south was closing on to open revolt, while in the north the Shiī al-Ḥūtī Movement steadily increased its influence and eventually took over the capital Sana’a. Thus for a brief moment, the al-Ḥūtī Movement became the legal government, though heavily disputed. But did not last long, as neither the internal conditions were ready, nor the regional powers with Saudi Arabia at the forefront would not allow this movement to take hold in their neighborhood. Especially since in the past they waged devastating – though unsuccessful – wars against it.

In February 2015 the whole constellations blew up, and the confusing chain of events, later on, led to the formation of a war coalition led by Saudi Arabia. Though soon enough the coalition narrowed down to practically Riyadh and Abū Zabī, the war, which in the beginning seemed to be only a brief and easy operation dragged on and started to put a heavy toll on the intervening states.

Despite all odds, Sana’a managed to hold on and in the last few years managed to hit back severely at Saudi Arabia and the Emirates. The al-Ḥūtī troops managed to liberate most of former North Yemen reaching the gates of the strategic city of Ma’rib. A city that during the last two years came close to liberation two times, yet for some reason reasons never fell.

While steadily sinking into one of the biggest humanitarian crises on the globe, the war between the al-Ḥūtīs and their tribal allies, the Saudi-Emirati forces, and their mercenaries went on fighting without any major breakthrough insight. With the failed attempt to liberate Ma’rib at the end of last year the initiative once again passed to the Saudis and the Emiratis returning to the war. Yet once again Sana’a caused inflicted heavy losses on both the Emirates and recently the Saudis.

And in the last few weeks, it seems that the sides finally accepted the inevitable necessity to reach a comprise. Riyadh offered a peace conference, which was initially rejected by Sana’a, but it is still not final. Then Sana’a after another series of strikes upon the Saudis offered a ceasefire, which was eventually followed by a Saudi proposed one.

The fight is not over, but calmed down significantly, finally opening the way for a settlement. Considering the global and regional constellation is ideal, this might be the time to put an end to the war. But will it prevail?

The frontlines

The events of the current Yemeni crisis and how it broke out are confusing but have dealt with these before. Just like with the changes at the end of the last year, when the equation between Riyadh and Tehran started to change on the Yemeni frontiers.

In a very brief overview, the situation is complicated. The north is steadily in the hands of the Anṣār Allah Movement and their allies, led by the al-Ḥūtīs. However, they reached the end of the area they can secure with tribal alliances and military advancements, as beyond this sphere the movement has very limited support. Two key points remained. The port of al-Ḥudayda, was under control by Sana’a for years, but the Saudi forces in the area kept a tight siege, and the fragile ceasefire around the city was regularly breached. This is a vital point for Sana’a, as this major and fairly developed port could provide the necessary lifeline for Yemen’s economy. The other major point is the city of Ma’rib, the capital and the main control point of the province with the same name. This province with substantial gas and oil reserves and facilities to process them could make the north self-sufficient for the most essential fuel and industrial commodities.

During 2021 the al-Ḥūtīs launched two major offensives to take Ma’rib. Though they practically cut the city from all outer supplies by December 2021, the battle eventually reached a deadlock and the Saudi forces slightly managed to push them back. Both times the forces of Sana’a became close to finally taking the city, for reasons still largely obscure the clashes subsided. It was clear that the Ma’rib became a matter of bargaining between Riyadh and Sana’a on the one hand, and between Riyadh and Tehran on the other. Thus the city became a final part of a possible solution to closing the deal. A deal that hasn’t manifested yet.

As for al-Ḥudayda, this matter is also extremely important for Sana’a, and it had no chance to break the siege around the city. But then, for reasons still unclear in November the Emirati forces and their affiliates suddenly retreated from the area, prompting the Saudis to follow suit. It is still unclear what really happened and despite all expectations, no details have been revealed. It might have been part of the intensive negotiations at that time between the Emirates and Iran, or might have been other reasons, but the whole Yemeni west coast was likely to fall under Sana’a’s control. That, however, never came to be, as Saudi Arabia imposed a tight maritime blockade around the port. Especially after al-Ḥūtī troops detained an Emirati cargo vessel, which was delivering weapons. Though by January Sana’a was very close to reaching the very minimum of its objectives and creating a safe and sustainable area for any future negotiations, it failed to reach its final goal.

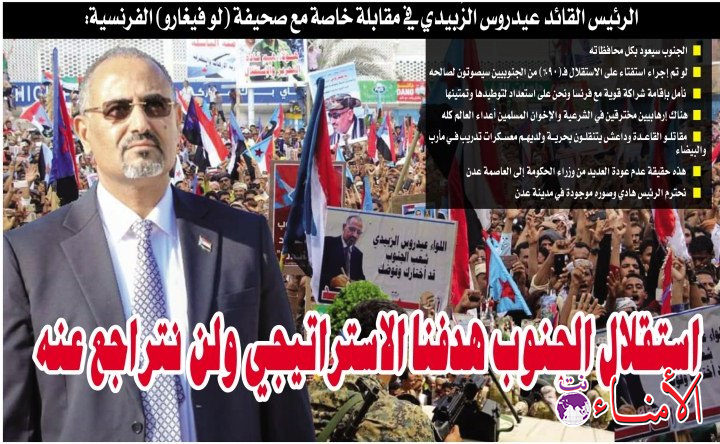

With these two key cities secured the al-Ḥūtīs would probably be ready for comprehensive peace talks for two main reasons. First, they have no hope to overrun the southern regions, where local resistance is much stronger. Second, they don’t even need to, as the areas run by ‘Adan is deeply divided between the so-called “Unity Government” led by resigned president Hādī and supported by the Saudis, and the Southern Transitional Council supported by the Emirates and led by ‘Aydarūs az-Zubaydī. Clashes and open battles are frequent between the two sides, just like within the various semi-independent armed factions nominally under the banner of the Southern Transitional Council. The fights between them also manifest the disputes between Riyadh and Abū Zabī, as they have fundamentally different ideas about Yemen. Riyadh initially imagined a united Yemen under its own influence under President Hādī, which by now has no real chances. The Emirates, working even against Riyadh, soon took on to support the Southern Transitional Council, the loose umbrella of the southern separatist forces, to carve out a new South Yemen under its influence.

By now Riyadh is only looking for a face-keeping solution to end its military presence and salvage some of its interests, while the Emirates is not ready to let its possessions go. But as it has doubts about how much could it protect its southern vassal alone, it needs the Saudis to stay, at least a comprehensive solution is reached.

The web of politics

The war in Yemen in essence is three major wars in one. One within the state between the north led by the al-Ḥūtīs, and the south being torn apart between the separatist aiming for a sovereign state and the unionists hoping for a reunited Yemen.

Behind them, there are strong regional interests, as Iran would welcome a capable ally right on the Saudi doorsteps, while the Saudis – and many Gulf parties as well – want to prevent this by creating a weak and exploitable vassal. Between the two, however, there is a fierce rivalry between Saudi Arabia and the Emirates both pushing their own allies and agendas.

So while a short-term local peace deal in Yemen is possible, the overall solution is still very far. Because it requires a number of conditions in the region, which are way above the Yemeni sides.

How did it reach this point?

The most important theme on the battlefield in 2021 was the siege of Ma’rib, which came close to total liberation on two occasions, but eventually, neither attempt succeeded. The main reasons behind the relative success of the Sana’a troops were that a number of local tribes were won over by Sana’a, the opposing side was deeply divided and the Southern Transitional Council gave little assistance to the crumbling forces of Hādī, and the Emirates did not intervene. Though the Emirates officially ended its mission in Yemen in August 2019, in reality, it was more of a policy statement and never pulled its troops completely out. It also kept financing the still involved Sudanese troops in Yemen and also kept on its financial support to the Southern Transitional Council and a number of other radical militias. However, it was true that the Emirates largely toned down its direct involvement.

That is until December 2021, when the Abū Zabī relaunched its large-scale activities, especially around Ma’rib. It also mobilized the infamous al-‘Amāliqa militia under its influence, which showed the biggest success around Ma’rib. That move was largely due to the ongoing troubles in the Saudi-Emirati relations and Riyadh drifting farther from its partnership with Abū Zabī at the time, which prompted the Emirati leadership to help the Saudi forces pinned down at Ma’rib a helping hand. With this renewed Emirati help from December 2021, the al-Ḥūtī advance was halted, but the step somewhat surprised Sana’a. Especially after successful high-level security meetings between Iran and the Emirates, it was believed that the Emirates will not interfere in the matter.

The result was a devastating and shocking hit by the al-Ḥūtī forces on 17 January 2022 against the Emirates. The airport of Dubai was hit by two airstrikes, completely bypassing all air defenses. At the same time, Emirati forces were hit within Yemen as well. These attacks and the precise hit in Dubai on the next arms shipment to Yemen indicated alarming Yemeni intelligence capabilities. The hit was repeated two other times, last on 25 January and these three Hurricanes of Yemen Operations put together showed that while Sana’a cannot break the stalemate around Ma’rib, it has devastating methods to hit back. The Saudi response was a massive barrage of airstrikes in Yemen vowing to destroy all Yemeni drone and missile facilities. However, beyond the destruction, it was clear that the Saudi intelligence cannot pinpoint all these facilities and cannot prevent further retaliation from Sana’a. Also by this point, the Saudi air forces ran out of sensible military targets and resorted to hitting random facilities in Northern Yemen.

Around the same time as the first attacks on Dubai Sana’a hinted that it is ready for negotiations, embracing the formerly proposed Iranian peace initiative. The indication was clear that Sana’a cannot take Ma’rib, nor can it show the success on other fronts, and thus the initial fell back to the Saudis. This, however, did not open the path for negotiations just yet, as the Saudi leadership made a last attempt to gain success by renewed military operations and massive airstrikes.

In early March 2022, Riyadh announced hosting comprehensive peace talks with all Yemeni parties to end the war. This initiative was supported by the GCC willing to give political backing to the process, urging all sides, even the al-Ḥūtīs to join, who so far gave mixed signals, but chose to stay away. The talks have indeed started in Riyadh on 30 March, so far without Sana’a and without tangible results.

In this political deadlock, the al-Ḥūtīs showed once again how much they can hit back at the Saudis and that any attempt at a peace agreement without them will be doomed to fail. On 24 March they carried out yet another set of devastating hits against the Saudi kingdom, paralyzing the Saudi oil facilities for days. Which is in the middle of the Ukrainian crisis is a huge problem, and not only for Riyadh. But with this the futility for both parties to end the conflict with a solely military solution became evident. And finally, the path for a dialogue opened up.

The ceasefire and its details

After the so far last major salvo launched on late 24 March by Sana’a giving a sobering reminder to Riyadh that it cannot overcome the Yemeni forces and cannot put an end to their devastating retaliation, it came as somewhat a surprise that on 26 March Sana’a offered a 3 days unilateral ceasefire. Especially that upon the last attack the Yemeni forces announced further strikes on specific targets. It was not accepted by the Saudi leadership and on 27 heavily bombarded Sana’a and several Northern territories in a futile attempt to seem resolute and destroy the Yemeni armaments capable of further missile strikes.

This is a recurring theme, as Riyadh had tried on many occasions to uncover and destroy all Yemeni missile and drone capabilities, but these attacks were never successful, regardless of their massive scale. It was probably obvious at the Saudi military command as well that this retaliation might have been face-saving, but could not be successful, and on 29 March Riyadh also announced a unilateral ceasefire, with the announced cessation of all military operations in Yemen.

Given the scale of animosity and distrust between Sana’a and Riyadh, it is not surprising that neither sides were ready to take on the other’s offer for a ceasefire, but nonetheless, there were two unilateral ceasefires at hand. At least officially both sides halted major operations. Though so far there have been reports of Saudi airstrikes from the very early days of the ceasefire, the operations cooled down significantly. This was the opportune moment for the U.N. to intervene, with significant Iranian and Oman mediation, as we came to know later on. Though neither sides like to share details, what seems to be likely that Oman reached out to the Saudis, while Iran to the al-Ḥūtīs and pressured them to accept at least a temporal ceasefire. Which could be developed towards a political process in the Riyadh talks. On the other hand, Oman and Iran engaged the U.N. Special Envoy to offer a U.N. supervised ceasefire, which could be accepted by both parties, as neither was willing to directly negotiate with the other. This U.N. offer was proposed before for the length of Ramadan to facilitate negotiations, but on 31 March it became accepted and came to immediate effect. But what does this ceasefire deal contain?

The most important thing is that while being a U.N. ceasefire, no U.N. or international agencies are monitoring it. It is based solely on the goodwill of the two sides. While this might seem surprising, it is actually a promising formula, as before all internationally mediated ceasefires were both broken a played around, only to give a further argument for international unbiasedness and to continue the fighting. Also, no international agency has the capacity to fully monitor the agreement and act as a neutral supervisor. The solution was to grant major concessions to both parties, under significant security guarantees.

The most essential agreement is that all military operations must halt and all fronts freeze as they are. Though not specifically mentioned, in reality, it means that Sana’a agrees not to carry out further airstrikes against Saudi Arabia, or the Emirates, and will not try to liberate Ma’rib. On the other hand, the Saudis also should stop all airstrikes, and not use the ceasefire to break the siege around Ma’rib. That gives ground for smooth negotiations in Riyadh, where the Saudi government could unroll its newest offer, and finally start to end its military mission in Yemen.

For that, in exchange, the al-Ḥūtīs also reached many of their most essential demands. 18 ships could enter the port of al-Ḥudayda and unload unhindered. These ships could only carry oil, which is much needed in the North now. This shipment will let the economy in the North survive and somewhat ease the humanitarian burden. Also, the airport of Sana’a would open up, though under very limited circumstances. Only two flights per week are allowed, and only to Egypt and Jordan. But it is nonetheless significant, as certain goods could be transported and some level of movement is granted. Yet because it is only operated via Egypt and Jordan, the Saudis are guaranteed that this way no military equipment, or any form of direct Iranian support is not flowing through.

Apart from that, all movement within Yemen, especially around Ta‘izz must be allowed by both parties, which finally gives a chance for humanitarian corridors to be opened, goods and materials can flow and international aid can reach both sides. Though it is less public, it was also accepted that both sides use these opportunities for prisoners exchange, which has happened already.

What is specifically interesting is that while the port of al-Ḥudayda and the city of Ta‘izz – around which there has also been fierce fighting in the last few months – were mentioned in detail, there was no word about Ma’rib. There is no signal about the fate of the city, which is probably still the most crucial element of bargaining between the sides. Yet, this also signals that this ceasefire is only a temporal solution.

At the current state, this is not much. But it is a breakthrough, nonetheless. Such statewide ceasefire hasn’t been reached since the war started in 2015, only fragile local agreements. Goodwill was shown for and by both parties, which could signal that the futility of the war was finally understood and accepted. The ground for further negotiations was established and it is further promising that the ceasefire has no deadline, it is automatically renewed if no sides object to it.

Can it finally bring peace?

The answer to this question largely depends on two key factors. What do the individual sides try to achieve in both the short and the long run, and what do we mean by peace.

While there is a good chance for peace on the international level, meaning the war between Sana’a on one side and Riyadh and Abū Zabī on the other, this is probably just a prelude to a new internal war in the south. In case this can be avoided in any format, most likely by removing Hādī and his government, the most likely scenario to come is the de facto reinstallation of two separate Yemen. And from that position, all parties can settle their ranks and hope for better conditions later on.

Here we should understand the motivations of all parties, and by this, we can understand that this is the most logical and realistic settlement for all. Saudi Arabia is desperately in need to end this war and fighting draining its military forces and budget with a war promising no benefits. Now a settlement with Iran seems viable enough for Riyadh to hope that North Yemen will not be a direct threat, only an inconvenience, which can be economically pressured later on.

To achieve this they have to accept a separate South Yemen, which will be under Emirati influence. Here the Saudis have no hope to establish control, and since Iran will be equally alarmed by possible Emirati-Israeli cooperation here, Riyadh can gamble on the Iranians to check this development. On the other hand, they finally have to remove Hādī, who is much more of a complication than a solution at this point. That process has already started by the offered comprehensive peace negotiations under GCC supervision. Also, taking advantage of the current relative calm, under Saudi pressure President Hādī on 7 March transferred all of its theoretical powers and prerogatives to a Presidential Council. With this Hādī effectively gave up his powers, as he will not be a member of the council. Also, the main official task of this council will be to directly engage the Anṣār Allah Movement for a political settlement. It is interesting to note that with the same step Hādī sacked all his deputies and chief advisors. Out of 7 members of the new Presidential Council, three were military men.

They are ‘Aydarūs az-Zubaydī the President of the Southern Transitional Council; Ṭāriq Ṣāliḥ nephew of former President ‘Alī ‘Abd Allah Ṣāliḥ and commander of his elite Presidential Guards unit, who at one point was allied to the al-Ḥūtīs, but eventually turned on them and rallied the forces once formed the backbone of the Yemeni army; and ‘Abd ar-Raḥmān Abū Zar‘a, a shady fundamentalist, who which substantial Emirati support managed to form the infamous al-‘Amāliqa Battalion uniting the most radical Sunni fundamentalist elements.

The other four members are more political figures with much less influence. They are Sulṭān al-‘Arāda, the mayor of Ma’rib who is from the city and was the most essential link with some of the local tribes; ‘Abd Allah al-‘Amalī, the director of Hādī’s office; ‘Utmān al-Mağlī, an Emirati supported businessman and former Agricultural Minister, the only member from the north, as he is the Sheikh of a major tribe in Ṣa‘ada Province; and Farağ al-Baḥasnī, the governor and military commander of Ḥaḍramawt Province. Power was practically handed over to the southern separatist strongmen, who can fend off Sana’a together, and the concept of a united Yemen is thereby abandoned.

The indication is that all militia’s leadership, both the Saudi and the Emirati supported ones would unite with equal theoretical rights in one governing body, only to travel to Riyadh – or any other negotiating location – and sign a peace deal. So far Sana’a has rejected this move and shows no interest in directly engaging this new governing body, but that might change soon.

As for Iran, this scenario is acceptable, as this would give space for future peace negotiations with the Gulf states. Which are all going relatively well, despite the recurring complications. Now Iran is also stimulating negotiations with the Emirates and here a temporal solution can also be reached. If the Emirates agree not to allow a major Israeli presence in Southern Yemen and in the Gulf, Tehran can turn a blind eye to its presence there. Which is a huge asset for Abū Zabī. Part of this process is that Iran is varied about Abū Zabī’s recent mediation between the Arab states and Israel, especially around Syria. So both parties can settle for such a deal.

On the local level, as mentioned before, Sana’a in the long run can hope to eventually take over the south, but only if the separatist forces are divided. Now, this is not the case. The current state of Yemen, especially the north is an appalling economic and humanitarian situation. It has to settle its ranks before any hopes for unification. But with a successful deal with access to international trade, even if this includes a ban on any military cooperation with any state, with Iranian help the economy can be relaunched. Sana’a is much more likely to achieve order and some resemblance of normality than the south, where eventually the militia leaders might turn on each other.

As for the southern separatist, they have no interest in Sana’a. They are closer to achieving de facto control over an internationally recognized South Yemen – under any official format – than ever before since so far this was not only objected to by Sana’a, but also by Riyadh and Tehran. With such a deal they can hope to create their own state and with Emirati support and some level of Israeli backing, this might be sustainable.

The conditions are all set for settlement. Not for a solution, as all parties might just hope that in time conditions will turn to their favor, but a temporary acceptable deal giving them the minimum of their needs.

The path for two Yemens once again starts to be clear. That seems to be in the best interest of everyone now. But how it will play out shall be seen by the success of the current ceasefire and the future negotiations in Riyadh. Which later will probably fail, but will likely pave the way for another round of talks at another, more neutral location.