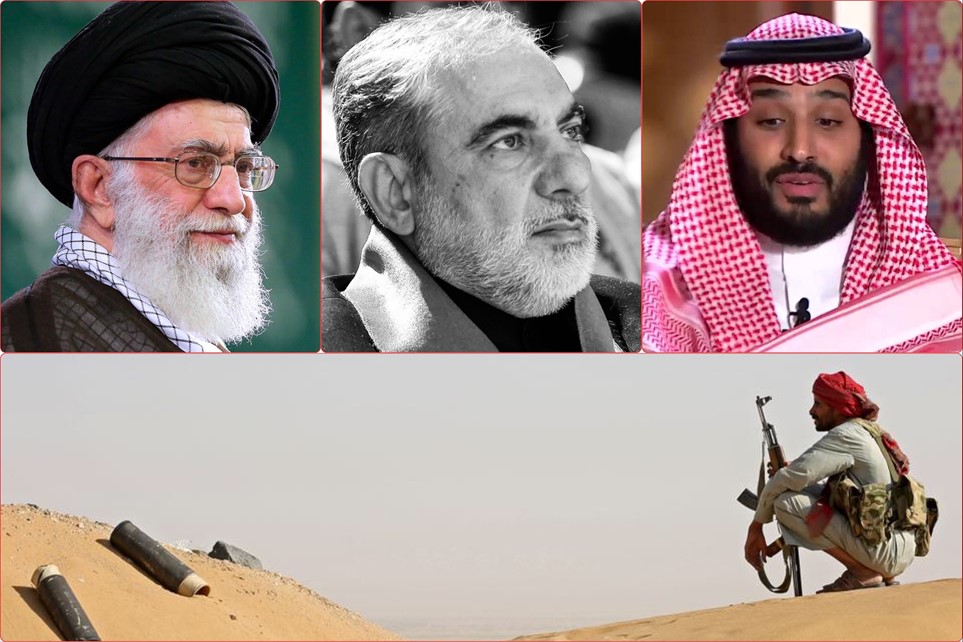

On 21 December 2021 Tehran announced that its ambassador to Sana’a Ḥasan Īrlū passed away. Two diagonally different versions came to light about the event. The official version given by Tehran stated that Īrlū passed away in Iran shortly after returning from Yemen, and that he was in a worrisome health condition following a Covid infection. The other version mostly raised by Saudi commentators suggests that in fact Īrlū died in a Saudi airstrike, or shortly after, which was carried out against the al-Ḥūtī troops at the frontlines.

The event itself, with the massive controversies and contradicting accounts surrounding it once again poisoned the recently warning relations between Tehran and Riyadh. This is, however, only the latest point, from where to Saudi-Iranian relations took a downturn.

In the same context the operations of Sanaa’s troops in Ma’rib which all seemed very promising at November came to a halt once again. The al-Ḥūtī troops diverted their operations to other parts of Yemen, mostly along the border with the Saudi Arabia and Šabwa, suggesting that the liberation of Ma’rib either became too complicated, or that the matter once again entered the realm of regional politics. And as both the leadership in Sanaa and its allies in Tehran see more benefit in pressuring Riyadh than a swift victory other pressure points were looked for.

However, the dire situation of the Saudi campaign in Yemen seems to meet its final agony. This forced the Saudi troops, especially after the other humiliating setback at al-Ḥudayda to also alter their tactics. This resulted in a massive bombing campaign against Sanaa and Yemeni civilian infrastructure all around Northern Yemen. Which Saudi commentators at this point don’t even deny to serve the sole purpose to pressure Sanaa for a settlement.

What does this setback mean for the prospects of the recently warming Saudi-Iranian relations? Where does the Yemeni conflict heading? And how much the death of Ḥasan Īrlū changes the equation?

The death of Ḥasan Īrlū

Ḥasan Īrlū was born in a suburb of Tehran in 1959 and studied foreign relations in the university of the Ministry. He received a doctorate in international relations and started to work in the ministry. Also during the war with Iraq in the ‘80s he joined the army, and as a devoted member of the revolutionary government he joined the ranks of the elite Revolutionary Guards. A path taken by many top members of the current Iranian political establishment. This does not necessarily mean a distinct military career, but shows the intimate relation of Īrlū to the administration overall. It is customary that many top and mid ranged officers of the Revolutionary Guards even after their military service either continue within this establishment as reliable administrators, or continue state administration administration or private businesses benefitting from their relations with former comrades within the Pāsdārān.

Not much is confirmed even by Iranian forces about Īrlū career within the Revolutionary Guards, except that he fought in the frontlines and at least in one occasion suffered Iranian gas attack in the ‘80s. However, this made him knowledgeable about Arab affairs and upon entering diplomatic service in the 2000s he was considered a reliable expert about the Arab world. His speciality was, however, Yemen, a then relatively dark spot in the Iranian strategic planning. Eventually he became the director of the Yemeni section in the Iranian Foreign Minister years before the current war in Yemen started in 2014. It is often cited that he was intimately involved in the Iranian operations in Lebanon during the ‘90s and early 2000s, yet little is confirmed about this. However, the relatively scarce information about him suggest that he was a somewhat high profile strategist either in the Ministry, or in the Revolutionary Guard. Though the two do not exclude each other.

His name became more famous after the Saudi campaign against Yemen started in 2014, as Īrlū was believed to be the top Iranian strategist about Yemen. And he is tough to be the mastermind of the nature of policies, political, economic and military help provided by Tehran to the forces in Sanaa. As a major step in the support Tehran provides to the al-Ḥūtī – officially by Tehran limited to diplomacy and humanitarian aid – in August 2019 Sanaa appointed its first ambassador to Tehran. This came at a time, when Sanaa’s international representation was virtually non-existent, as all former Yemeni diplomatic mission were either halted, or at least officially represented the exiled government in ‘Adan. Apart from Iran, the al-Ḥūtīs only had a de facto liaison mission with the U.N. mediation and humanitarian efforts. Logically, as they controlled a major part of the country. But this was far from international recognition. A thing Sanaa government still aims for, but almost entirely refused.

Appointing an ambassador to Tehran, especially that this was accepted by Iran was a turning point, which represented that the al-Ḥūtī Movement survived the Saudi campaign, consolidated its positions and the phase of expelling the Saudi-Emirati forces have begun. Though Iran returned the favor, for long it was not officially acknowledged who the new Iranian ambassador to Sanaa would be. Only in October 2020 it became official that Ḥasan Īrlū is this new ambassador, when he arrived to Sanaa. Tehran maintained that there is nothing extraordinary in the event, as it always maintained its diplomatic relations with Sanaa never recognizing the exiled government led by former President Hādī. However, there were contradicting accounts whether Riyadh knew about the ambassador’s arrival directly from Tehran, was he smuggled in aboard an Iranian humanitarian plane, or by the U.N. Either way, the step caused major uproar by the Saudi endorsed Yemeni government in the south, as this came at a time, when the al-Ḥūtī Movement at that time secured gains around Ma’rib and for the first time managed to carry out painful strikes against Saudi Arabia deep within the kingdom.

Upon Saudi and Yemeni pressures Washington condemned the alleged breach of international protocols. The Saudi-American claim was that Īrlū was an active member of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards, meaning direct military involvement by Tehran. And from that point on claims and alleged secret video leaks became regular portraying Īrlū as a de facto Iranian governor for Yemen, a sort of “handler” of the al-Ḥūtī Movement. Whatever was the true extent of his mission, it is undoubtable that with Īrlū one of the top Iranian experts took over Tehran’s activities in Yemen. And these proved to be successful eventually, firmly consolidating the government in Sanaa. It is highly doubtful whether he ever took part in military operations in any capacity, nonetheless his efforts were surely beyond a conventional ambassador. And even later Iranian accounts (Magyar) admitted that Tehran had by that time military experts on the ground.

He spent slightly more than a year in Yemen, when in late December it was suddenly announced that Īrlū had to return to Tehran, where he died following a Covid infection in Yemen. By all accounts the plane carrying him home came from Tehran to Sanaa airport and transferred him with the full knowledge of Riyadh. Officially this step came as a gesture in the recently warming Saudi-Iranian relations.

From this point, however, the accounts hugely differ. Tough officially Tehran refrained from blaming Riyadh, even the official statement indicated “delay by certain regional states”. Iranian and Yemeni accounts in Sanaa maintained that Riyadh was informed and requested to allow the humanitarian extraction of Īrlū, which was followed a two days bargaining, when the Saudis asked for compensation in the form of Tehran pressuring Sanaa to stop the operations against the Saudi and allied troops. Especially around Ma’rib. According to this version the delay largely contributed to Īrū returning to Tehran only in a fatal state of the sickness.

Riyadh, on the other hand only maintained that while Īrlū was an “unofficial” ambassador, nonetheless they approved his rescue and cooperated. Saudi commentators stated that Riyadh gave permission for the mission “within 48 hours”, which somewhat confirms the bargaining. Almost immediately, however, Saudi commentators and various videos showing alleged pictures of Īrlū flooding the social media platforms claimed that the Iranian official died in result of a Saudi airstrike.

Losing such a valued expert is a major loss for Tehran, and by this they lost their key liaison officer in Yemen. That is not an irreparable problem, but the later Saudi claims soured the tone between Riyadh and Tehran once again. Either they only delayed to provide help, or directly attacking the ambassador, the matter casts serious doubts about how far negotiations can go between the two sides. Which are further complicated by the sudden turn in Riyadh’s officials tone and the Saudi troops’ tactics on the ground.

The military deadlock

The military conditions by November 2021 fundamentally changed for the benefit of Sana’a, though an overall breakthrough is far from sight. The situation is, however, grave enough that prompted both political and tactical changes by Riyadh, which so far brought little result.

On the political front Saudi Crown Prince Muḥammad ibn Salmān took on a regional tour visiting all member states of the GCC, which aimed to rally at least political support for the Saudi position in the region, especially about Yemen, but also to provide an opportunity for mediation to Turkey and Iran. Two key elements were to gain support from Oman for mediation, and to settle the troubled relations with the Emirates, which might be able to rally Emirati support on the ground once again. Only the latter proved to be somewhat successful, as the Emirates once again lent support for the Saudi war efforts with drone strikes and via the Emirati supported militias. Though this is largely hidden from the headlines.

This Saudi activity was largely caused by the fact that by late November the initiative was firmly in the hands of the al-Ḥūtīs, who were once again in the offensive. Fightings concentrated to four key fields. Ma’rib and the fronts around it; the port of al-Ḥudaydā, from which the Saudi-Emirati troops in early November suddenly retreated in a still dubious move; the Saudi-Yemeni border region and the Province of Šabwa southeast of Ma’rib.

While news about the liberation of Ma’rib were a daily phenomenon in October and November, they practically disappeared since then and there are little reliable news about this front at this time. Which suggest that the frontlines once again froze down and both parties are looking for breakthrough somewhere else. The port of al-Ḥudaydā after years of fierce clashes and the regular breaches of the U.N. sponsored ceasefire here came firmly under control by Sana’a after the Saudi-Emirati troops withdrew. The port is extremely important, since this could finally be a reliable gateway for Sana’a to the outer world, regardless of the international blockade and the U.N. monitoring mission in the region. Riyadh is extremely upset from this development, but had little chance to launch yet another offensive to retake it, as its frontlines in many other fronts are crumbling. Therefore the Saudis chose to gain international support to increase the blockade on the port and close it down completely, but portraying it as a major missile and smuggling basis.

On 08 January 2022 Saudi Coalition spokesman Turkī al-Mālikī held a press conference about the Saudi war effort in Yemen. During this al-Mālikī showed a footage allegedly proving that in the port of al-Ḥudaydā there is a ballistic missile assembly and storage yard and also from here missiles are smuggled with Iranian help. The footage, however, proved to be false, taken from an American movie called Severe Clear made by American troops in Iraq.

Roughly at the same time when news about Ma’rib once again became scarce reports claimed the province of Šabwa flaring up once again, after the failed campaign by Sana’a here in 2015. Sana’a claimed that most of the northern part of the province came under its control. On the other hand Riyadh claimed that while there were battles, the al-Ḥūtī troops are once again beaten back. A press conference held on 11 January by Turkī al-Mālikī with the Saudi supported governor of the province aimed to prove this point. The truth is hard to check, but probably lied somewhere in the middle. Nonetheless, it shows that the al-Ḥūtīs try to break the tie around Ma’rib by cutting the region from the south and the east, which would bring the liberation of the city closer, or force Riyadh to concessions. An objective still hasn’t been reached.

There are also conflicting reports and analyses about Yemeni progress along the Saudi border. This, and the renewed Yemeni missile strikes against the kingdom shows that Sana’a, while for some reason not progressing at Ma’rib, still tries to break the tie and still haven’t lost the initiative.

The new Saudi military doctrine

After al-Ḥudaydā the Saudis were clearly on the back foot and urgently needed to change the equation. Also to prevent the loss of Ma’rib and minimize their losses. Riyadh was finally ready to negotiate, but that needed major concessions from Sana’a that it will accept Saudi and Emirati presence in the south in the long run.

For that a new strategy was adopted. A fierce bombardment campaign against Sana’a and the civilian infrastructure in the areas controlled by the al-Ḥūtīs. The first major step was the bombardment of the Sana’a airport on 20 December 2021 only hours after a U.N. mission left the airport. Riyadh held that the attack was just, as it was a military target, after the al-Ḥūtīs used it for military purposes. The attack was a clearly symbolic, though brutal gesterue, and not only for the Yemenis, as for years the airport was not in orderly use, only accepting diplomatic, U.N. and humanitarian aid carrying planes. It was followed by a large bombing campaign against Sana’a and other northern Yemeni cities, openly attacking civilian targets as well. This was acknowledged by Saudi commentators also.

The result is doubtful, as Yemen is already in a shocking humanitarian state. This shows that the Saudis have a hard time to block the military moves of Sana’a. But it might not be a coincidence that lately Sana’a once again stated that it is ready for major talks upon the previous Iranian initiative. And this could indicate that now Tehran is ready to step in as an arbiter, or encourages Sana’a to start the peace talks.

Changing friends?

The deadlock seems to be complete. The al-Ḥūtīs are advancing and clearly won in the north. There can be further victories in Ma’rib and along the Red Sea coast, while the airstrikes are showing impressive result for them. That could make them optimistic. However, the state is in catastrophic conditions and the latest Saudi strikes against the civilian infrastructure shocked them. Regardless of all their achievements, they have not means to stop these. But the problem is that even bigger. They practically reached the last regions, which they can firmly keep in control. Gaining Ma’rib full of oil and gas, and liberating the port of al-Ḥudaydā are useful economic gains, but these are the last probable gains. So there is the problem. Where to go next? Either they continue their war directly in Saudi areas, which would bring huge international opposition, or progress towards the south. Yet there they would not be facing the inferior Saudi forces, but the hugely motivated and equally fierce Southern Yemeni militias and tribes. There is no rational in this, as such wars never proved to be easy. All previously North-South Yemeni wars were long, brutal and usually ended up with a compromise, even if the North gained the upper hand. Sana’a should lobby for a settlement with the south, but that can hardly be achieved, as long as Abū Zabī and Riyadh have an overwhelming influence over any southern political formation.

As for Riyadh, it also reached a dead end. It wants to bring out their battles troops, not sending in more. It would welcome a settlement in Yemen, but not by relinquishing all influence in the south. The Saudis have no means to end the continuous Yemeni airstrikes, and it is clear that Washington will not protect them from this. So lately Saudi Arabia took a step formerly unimaginable. Launched a ballistic missile and air defense program in cooperation with China. A step that shows that finally Riyadh is also ready to reevaluate its partnership with the Americans. A very alarming development for Washington.

The result is two different ideas how to progress from here. Though ironically both sides are claiming further military gains, both are ready to end the war. Sana’a wants a settlement with the south, either without any foreign interference, or with wide international mediation. None of these seem to be likely. Riyadh also wants a settlement, even with recognizing the government in Sana’a, but in a face saving manner. Holding on to military positions in the south. Also not a likely scenario.

This suggests that once again a longer period come, where there is no progress, only the humanitarian conditions worsen. And from here the solution will either come renewed violence in a year, or less, or by international mediation. And here the most promising is if Iran and Saudi Arabia can reach an agreement.

The progress of the negotiations between Riyadh and Tehran, mostly with Iraqi mediation was promising in the last few months. This was clearly shown by the lack of Saudi objections to the nuclear negotiations in Vienna, unlike the time when the JCPOA was reached. However, the death of Ḥasan Īrlū and Riyadh’s behavior about it cast a dark shadow over the possible outcome of any future settlement.