On 22 July 2023 Algerian President ‘Abd al-Mağīd Tabbūn returned to Algeria after a long and truly impressive journey. First, in a seemingly unremarkable visit to Qatar hosted by Emīr Tamīm himself on 16 July, Tabbūn had an almost week-long journey to China between 17 and 21 July. Here, aside from a number of sensational factory visits and a very warm welcome by Chinese President Xi, the two sides agreed to renew and even enlarge the comprehensive strategic partnership, including the fields of military and security as well, and China announced to invest $36 billion in Algeria in the near future. This was tied to the renewed Algerian desire to join the BRICS group as soon as possible, and very obviously Algeria was treated almost as an equal – presented by the Algerian side -, but at least as a very central partner. Truly such treatment is seldom given to a country with the economic weight as Algeria has.

On the way home, Tabbūn stopped by Türkiye to be received for a day by President Erdoğan, a once again re-emerging partner of Algeria. Thus concluding a more than week-long journey taking Tabbūn to both ends of the Turkish-Qatari tandem, and having a very impressive – and even more successful – visit to China.

This trip comes shortly after a month of his presence at a major economic forum in Saint Petersburg in the presence of President Putin, who called Algeria a “key partner in the Arab world and in Africa”. This step, which was supplemented by signing a number of key partnership agreements, meant an obvious defiance of the previous Western warnings that Algeria should distance itself from Russia. Yet, despite these warnings, the mounting pressure on Russia for its war in Ukraine, and the still precarious economic conditions within Algeria and in its immediate neighborhood, Algiers is gaining influence, not losing. As this, last July trip clearly shows.

And then on 26 July something remarkable happened, a new military coup in Niger toppling an adamantly French-oriented president, while the new establishment demanded ousting all French presence and establishing strong ties with Russia. To which the Second Russian-African Summit recently held in Saint Petersburg Moscow responded by pleading $90 million in support of the African countries. The development in Niger, important as it is, might seem unconnected to Algeria, but behind the scenes, there are shifts in Northern and Central Africa, in which Niger is a key point. In these developments, Algeria is finding very influential and capable global allies and gaining a role that is way beyond its economic and military potential, but nonetheless shows its ambitions. A role that in the last two-three years yielded truly impressive results for Algeria.

The role of France as a catalyst

Algeria has a significant role now as a major source of natural gas in the closest possible vicinity of the EU that is not tied to Russia and has by its strategic position controls significant passageways for future supply lines between Central Africa and Europe. That role alone grants much leverage to Algeria and largely explains why such defiant warming with Russia and China attracts little attention and criticism. But is Algeria really just that? A massive oil and gas deposit vitally important now, at a time of global energy crisis, but otherwise unimpressive and almost insignificant?

To truly grasp the role Algeria started to take we must go back a little and clarify the region around it. Especially to its south.

Northern and Central Africa is a historically French-dominated part of the world, which used to be all part of the core French colonial empire. Though after World War II., like all colonial powers, had to accept the inevitable track of giving up colonial rule and granting independence to its former colonies, Paris was not about forfeiting its influence here. France not only managed to keep its economic interests in these newly independent states but with a series of military agreements maintained a dominant role in the political developments. And thus remained a key arbiter of internal and interstate developments. That is despite the growing influence of the Communist block and the Soviet help given to a large number of states in the region.

That Soviet-Communist rival, however, collapsed at the end of the ‘80s. Which brought about the collapse of a number of former allied, or pro-Soviet regimes. It was the natural order of things that such shifts created a vacuum of dominance, which France rushed to fill building upon its former military treaties and safeguarding its vital economic interests.

This French resurgence was already significant, when President Sarkozy took office in 2007. Yet under him, Paris sped up reestablishing its regional dominance. Not in small part due to the so-called Arab Spring, which once deeply undermined the former setup in Northern and Central Africa with the collapse of Libya and the security challenges it brought about.

This resurgence built upon the former military treaties, which allowed French military presence in a number of key Central African countries. At the France-Africa Summit in 2010 in Nice France underlined establishing a strategic partnership based on regional and subregional organizations, fighting against common threats – in which after 2012 terrorism became a key theme – and protecting common interests. To that end, France pledged €300 million between 2010 and 2012 to African states and organizations and agreed to train 12000 African troops. All the within U.N. endorsed regional “peacekeeping” organizations and with substantial British and American support. In that trend toppling the Libyan government, and a successful leading role in the anti-terrorist campaign in Mali after the December 2012 coup were vital steps.[1]

Following the coup in Mali, which was largely caused by the overspill effects of the chaos in Libya orchestrated by – among many other – France with many of its African allies – Mali at the top of the list – the new French president at that time, Hollande used this opportunity to present France once again as an active military force in the region a launched operation Serval. In an attempt very familiar to the U.S. as well, Paris sought to gain financial support for this operation from the Gulf states, officially fighting against terrorism but largely protecting its own influence and thus its own economic interests. In December 2012 the U.N. authorized the military operation of ECOWAS (Economic Community of the West African States) with massive French involvement, and thus Mali practically became a protectorate. A state, in which the former colonial power waged an anti-terrorist war, largely successfully, but never completely fulfilled its mandate, thus terrorism, though on a much smaller scale remained a permanent phenomenon. [2]

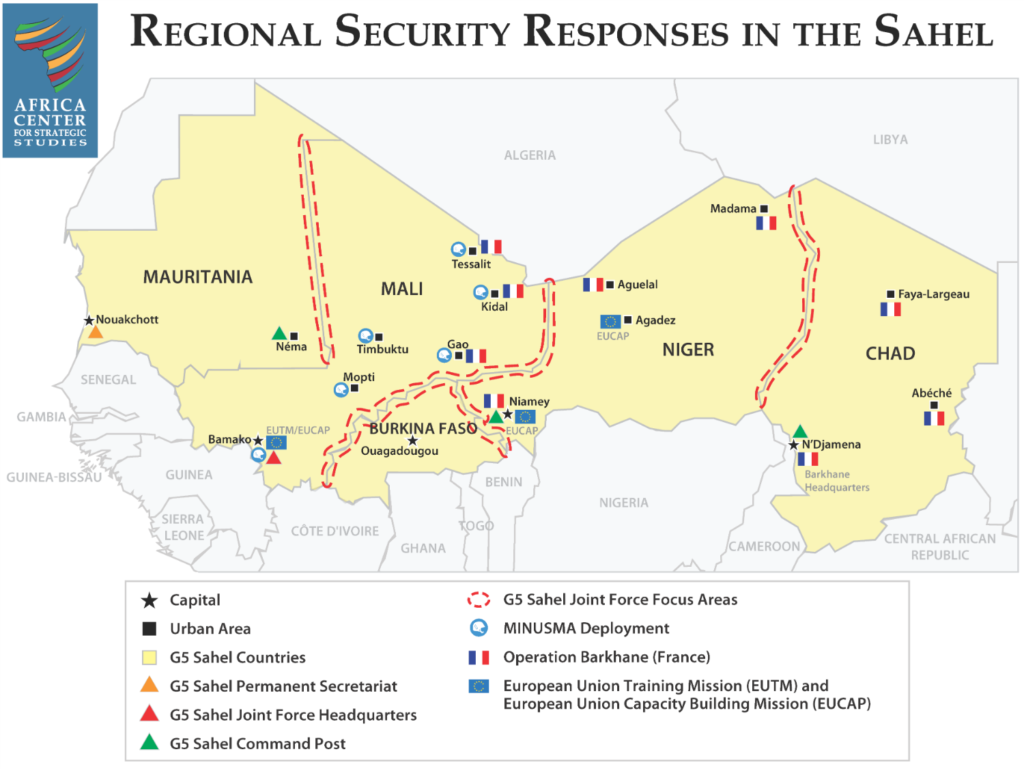

France, however, did not stop here, and using the pretext of growing Islamic terrorism in the Sahel region and the joint efforts to tackle it galvanized more regional organizations and obtained financial support from the Gulf. The most important amongst these – beyond ECOWAS – was the so-called G5 Sahel, a regional organization made up of Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso Niger, and Chad with France as its outer support partner. The G5 in 2017 launched its Joint Force, a largely French umbrella massively using African human power, which became a bridgehead for renewed French military activity.

It should be kept in mind that France has had, and still has vital economic interests in these countries, as Mali is a major oil, gas, and mineral source for France, the third biggest gold producer in Africa, and a potential transit country once the pipelines from Nigeria reach Europe via Algeria. Niger on the other hand provides 33% of France’s uranium, which is vital for its nuclear energy that is the source of 80% of its electricity. Mauritania, as a vast, but largely barren country is a key access point to these countries, and Chad has had the most essential military position for France with the most stable military bases. Therefore the G5 was a huge step forward for French ambitions.

Very few states dared to keep away from this French-led regional partnership, and even fewer dared to voice major concerns. Algeria was practically the only major critic of this development, where traditional paranoia about French intentions fused with rightful suspicions that these steps might lead to undermining its national security along its southern borders. That developments in Mali might eventually push the terrorist organizations over to their own territories, inviting foreign interference. And it also massively curtailed Algiers’ ambitions for a leading role in the Sahel region. But paralyzed with internal conflicts, unfavorable regional conditions, and the lack of capable and willing global allies there was little Algeria could do. It had to wait hoping that conditions would eventually shift to its advantage. Which they did.

In March 2019 after Algerian President Bū Taflīqa announced his candidacy for the fifth time, though being practically paralyzed for years, a popular unrest swept away the Algerian establishment. The unstable conditions took years for the military and political apparatus to regain control under the new president, Tabbūn. Eventually under him and new army chief of staff Šanqrīḥa and a wide range of military purges managed to do, yet the country – and the president himself very literally – was hit severely once again by the Covid pandemic. Nonetheless, the new policy was forming as the Algerian establishment gradually regained control.

That new policy largely built on the former excellent partnership with Russia but also started to attract the support of Türkiye and Qatar, and even more importantly started to give unprecedented concessions to China. The fruits of these attempts are very obvious by now. Benefitting from the once again surging energy prices on the global market and the desperate need for alternatives to Russian energy resources Algeria started to have more leverage and a tacit, but very significant partnership developed between Algiers and Moscow.

And the dominos started to fall

The situation in the region started to take a sudden shift in 2020. Following irregularities in the elections during that spring in June 2020 the military led by Assimi Goïta led a military coup arresting Malian President Keita and Prime Minister Cissé – both being part of the military junta since the 2013 coup inviting France – and though ECOWAS demanded their reinstatement, the new regime only agreed to short term transitional period to be followed by renewed elections. However, in yet another coup in May 2021, the military junta of Assimi Goïta stabilized its grip on power and severed ties with ECOWAS. On 4 February 2022, Mali expelled the French ambassador and demanded France withdraw all its military force from the country. By late February that in fact took place, on 2 May Mali broke all military agreements with France. The vacuum was rapidly filled by Russia, sending military aid and advisers. Many suspected the help of the Wagner Group as well, and indeed in February 2023 Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov visiting Bamako promised massive military support against terrorism, which signaled that Moscow is taking over what Paris leaves behind.

On 30 September a similar scenario played out in Burkina Faso, where the military toppled the government only taking power in a coup the year before, and thus the lower cadres of the army took power. The new junta here as well expelled the French ambassador and on 19 February French troops had to leave Burkina Faso, while named Russia as a “reasonable choice and a new partner” for foreign help against Islamic militancy. And only recently at the Second Russia-Africa Summit in Saint Petersburg, Russia agreed to reopen its embassy closed since 1992 in Burkina Faso. The loss of this relatively small country was particularly bitter for France, as it was the base of its special forces in the region, the most impactful piece of its military projects.

The last “domino” fell only recently with the military coup in Niger. With a stunning similarity to the events of Mali and Burkina Faso, on 26 July the army in Niger overthrew President Muḥammad Bāzūm. At the first step only a section of the Presidential Guards arrested him and announced the fall of his government, but very quickly mass protests broke out in the capital Niamey and the army initially hesitant soon joined the coup. So much so that by 8 August the new regime appointed a new President and Prime Minister, ‘Alī Maḥmān Lāmīn Zāyin. And despite all pressures, President Bāzūm is still under arrest.

Just like in Mali and Burkina, France and the United States immediately announced sanctions on the country and demanded the reinstatement of President Bāzūm, one of the most loyal allies of France in the region. There are regular protests in the capital expressing hatred towards France and demanding help from Russia, and the protesters from time to time practically took a military air base close to the capital under siege. The new leadership has already demanded France pull out all its forces from Niger, annulled all military agreements with Paris, and after heated debates has even broke ties with ECOWAS.

Until that point, the events played out almost exactly as in the first two examples, but with the significant difference that this time both Washington and Paris and the ECOWAS are openly threatening with a military intervention. The military leaders of the ECOWAS member states with the participation of some non-member regional states held a meeting in the Nigerian capital and laid out a plan for invasion with an ultimatum that President Bāzūm must be reinstated until 6 August. However, not only that the new regime did not back down, but even before the ultimatum, on 1 August Mali and Burkina Faso announced that any intervention in Niger will be considered a proclamation of war against them and they will retaliate. Even though there is no such military accord between Mali, Burkina, and Niger. On the other hand, equally interesting, Chad announced that it will be neutral in whatever comes, so will not take part in any military conflict. This is tacit support for the new rulers of Niamey, as the support of the Chadian army and the military bases there would be heavily needed for a swift successful operation. Mauritania has also announced that it will not intervene.

Thus a very stiff showdown came to practically ending the key French project, which was the G5. On the one hand, there is the new junta in Niger enjoying the open support of Mali and Burkina Faso, while on the other hand, France still has military forces in the country, and its allies are openly threatened with an invasion. There are three possible outcomes of the situation. One is that France, just like in the previous two cases accepts the situation and pulls out. Thus the anti-French camp grows even more, stimulating even more changes in the region, especially in Chad and Mauritania. The second is an attempt for swift military action by the ECOWAS with French – and most likely American – support trying to free President Bāzūm and take over the capital, to give legitimacy for an invasion and forcibly reimpose the former leadership in Niger. That, however, has the high risk of an open regional war if such a commando operation fails, the army in Niger retaliates on the French troops and Niamey’s allies fulfill their vows to come to its aid. The third is that Paris buys time with negotiations and sanctions and in the meantime gives clandestine support for separatist groups in Niger, hoping that eventually, the junta would collapse internally. The first signs of that are already visible, as on 9 August former Tuareg leader and opposition politician Rīsā Āġ Būlā announced forming a new regional movement struggling against the junta in Niamey and asking for its overthrow.

Where the picture gets much bigger

There are already wide-ranging speculations that once again Russia had a hand in the events via the Wagner Group mercenaries, though all sources claim that there is no clear evidence for that. And even though Wagner leader Prigozhin has allegedly welcomed the coup, even the American administration claims no direct Russian involvement in what happened in Niger. Nonetheless, it is more than interesting that right from the beginning, just like in Mali and Burkina before, from the very beginning protesters supporting the coup raised Russian flags and slogans supporting Russian and Putin.

Even more interesting is that in his first major television interview after his return from China, Algerian President Tabbūn himself said that the crisis in Niger directly threatens Algeria. Though he did not express support for the coup, it was a subtle signal that Algiers is welcoming the events and discouraged all parties from military intervention. This is an indication that Algeria, though not openly, not only supports the new junta in Niger but even the support it gets from its neighbors.

At that point, there are two major questions. How could Russia in the middle of its war in Ukraine – not going overwhelmingly successful – and with all the sanctions against it, could, or would be interested to create such shifts in Central Africa? Especially in Niger, a landlocked country. Why would Russia spend any resources at all on such a distant operation, which has very little possible payoff, as not only Niger, but also Mali and Burkina Faso have very little economic, or political benefit to offer to Moscow? The second question is if such Russian influence is there, which is probable by the constant asks for support in every protest in these states, and that happens via a third party, which is this third party, and why do we never hear about it?

Looking at the map it is clear that Algeria offers a perfect access route to both Mali and Niger and via Mali to Burkina. Algeria also has massive knowledge and good connections in these states, especially since certain tribal relations in the Sahel connect it to these states. It is probably not a coincidence that the Algerian press warm-heartedly reported and welcomed the changes in all three states, and almost instantly after the coup, on 1 August Algerian Chief of Staff Sānqrīha arrived in Moscow negotiating with Russian Defence Minister Shoygu, most importantly the cooperation in defense capabilities. There Shoygu not only said that Russia is ready to support the Algerian army development, but also that the two states are allies aiming to form foreign policy together and that Russia values Algeria’s leading role in North Africa.

It is also not a coincidence that after the military support Mali got from Russia, and very likely from Algeria, and the political support Burkina Faso got, these states almost instantly announced that they are ready to defend Niger in case of a military intervention. This indicates that these states had intel beforehand about something about to happen in Niger before that coup. This leads to the conclusion that there is a joint policy to form a group of states opposing France in the region, which is incidentally forming a barrier between Algeria and the French sphere of influence.

What seems very likely is that Algeria is the key player behind the changes in Mali, Burkina Faso, and now Niger, with some level of support, or at least positive encouragement by Moscow. Algiers tactically denies any involvement, but gives massive support for these changes and lets Russia appear as the expanding power in the region. The concession Algiers gave to China also points to this direction pulling in possible Chinese support. Thus gaining an image of regional power, much bigger than its actual economic, or military power. Russian, however, is not deeply interested in these three African states. But it is interested in good relations with the Arab world through an influential state, and a key player in Northern Africa. It has a serious interest to keep a potential alternative to its own energy supplies for Europe close.

Algeria currently cannot sell its huge gas and oil reserves on other markets than Europe, though in the last few years, it seriously downgraded its ties to Spain and turned towards Italy. But with Chinese investments and possibly joining BRICS this might change significantly, selling more and more in the Asian markets. But because of its now crucial role in the European energy supply, Algeria does not receive major criticism for turning toward Russia, and even more toward China.

The other card in Algeria’s hand is the matter of African migration. With its long borders in the Sahel, its influence over the current Tunisian leadership, and its involvement in Libya, Algiers can have a mitigating role in the African migration towards Europe, but can also open these routes wide open.

These are all considerations that must be kept in mind when pressure is about to be placed on Algeria. But time is precious now. The energy crisis makes the Algerian economy skyrocket once again, but eventually, the need for its supplies in the European markets will fall back. Algiers needs to use its resources now to create a much better regional equation now, when it has leverage, but also find alternatives. But with the role it takes now and with its apparent successes, it is becoming a valuable asset for many.

[1] Sıradağ, Abdurrahim: Understanding French Foreign and Security Policy towards Africa: Pragmatism or Altruism, In Afro Eurasian Studies Journal Vol 3. Issue 1, Spring 2014

[2] Abdurrahim: Understanding French Foreign and Security Policy towards Africa: Pragmatism or Altruism