The last time we had the chance to focus on the Libyan crisis in July the situation was on the brink of open war. After the significant help, Turkey gave to its Libyan vassals in Tripoli the areas of control greatly shifted and Egypt seriously considered direct military intervention on official capacity. Cairo made all the necessary steps both politically and militarily to take a radical step and “solve” the crisis by its own likings with brute force.

Though we still hold that war was imminent, for a number of reasons that did not happen. Both Egypt and Turkey, the two key players behind the fighting groups had even bigger matters to attend to, and the local forces as well reached an equilibrium, a sort of practical ceasefire behind the mutual threats. And while the matter was precarious the Emirati-Israeli deal reshuffled all regional deliberations. Both parties had the chance, but also the task to rethink their strategies, and that created an opportune ground for an internal Libyan agreement, at least for the time being.

The main problem at this stage was not even the willingness, but the formula were to hold talks. While many partners, regional, European, Russian, and even Americans were ready to host negotiations, all these possibilities either failed before, like the Berlin conference less than a year ago, or the regional partners were all leaning towards one side.

And after Tunisia, Russia, and Algeria all failed to gain enough confidence, Morocco stepped in, and as it seems now, rather successfully. On 6 and 7 September in the peaceful outskirts of the Moroccan capital Rabat, in the quite town of Būznīqa a Libyan Dialogue conference was held, which on the 10th reached a surprising, but promising agreement. Just like 5 years ago, Morocco managed to break the ice. Moroccan Foreign Minister Nāṣir Būrīṭa deserved the celebration he got. But hopefully this time the result will be more lasting than the previous agreement.

What does this new deal contain and what does it promise for the Libyans? How did the situation get here from being only steps away from war? Is that the first major step for the long-awaited solution, or just it’s just a temporal halt in the war? This week Panorama focuses on the Būznīqa Agreement.

The Būznīqa Agreement

As mentioned before, many parties tried to host a dialogue between the Libyan parties, both in the region and internationally. No European mediation could be agreed upon for many reasons. Any European meeting naturally means a grand international conference with all parties involved, but this formula failed bitterly last year in Berlin. With too many parties involved emphasis naturally shifts from the internal parties to grand international and big power deals. However, this time these international positions are way too far from each other. The other reason why no European state could host such a dialogue was that Europe, the EU itself is utterly divided on the Libyan matter. Of course, all parties want some form of stability to make Libya a buffer and hold off the waves of mass migration, but while some, like Italy, want to achieve this via a deal with Turkey, other, especially France is deeply at odds with Ankara and want to limit Turkish activity in the Southern Mediterranean. France also has a much bigger fight with Turkey to which many other EU states don’t wish to join. This pattern showed that Europe is way too divided to be an effective host.

Russia also offered to host talks on the Syrian model, but since Moscow is part of the equation and by many parts of the problem that was also not feasible. Algeria also took great efforts to mediate. Algiers was especially aggravated by the prospect of Egypt arming and using the Libyan tribes in the war, knowing well that such a trajectory has enormous consequences to the Algerian security. But Algeria is also relatively close to Turkey now, and an active player in the scene, which led to its rejection. And finally Tunisia, more precisely the Tunisian President was keen to host a conference. It is Tunisia’s vital security interest to end the war in Libya, and especially to prevent a full-blown war, as it already took the biggest burden of the crisis. But Tunisia is also deeply divided internally, and the Libyan crisis manifests in the Tunisian inner politics.

In such a situation, while there was very profound Libyan need from both sides for at least a temporal solution, Morocco jumped in and organized a dialogue conference, being sufficiently distant from all parties. Yet at the same time, Morocco has the needed political and diplomatic weight for such mediation, unlike Tunisia.

The conference started on 6 September, and just like 5 years ago, in one of the peaceful and secluded summer residences of the Moroccan royal house in Būznīqa. Interestingly this was a very different model than the one used in al-Ṣuhayrāt five years ago, or the one held in Berlin last year, as it was not focusing on meetings between such major leaders, like Ḥaftar, as-Sarrāğ, or Aqīla Ṣāliḥ. There is a reason for that, which we will discuss here. But this time quantity ruled, or in other words a big number, but rather a low level participants were present from both sides, while the major outside players, like Turkey, Egypt, or France were kept away. They were not entirely closed out, as Morocco is politically close to France, while at the same time a similar meeting was held in Cairo as well, but the focus was on the “ordinary” representatives of both camps.

Though officially the meeting was supposed to go on for only two days, final agreement was only reached on the 10th. But at least it was not all futile. The main aim for both parties was to prevent the state completely being ripped into two between two rival camps and not to allow the creation of practically two Libya. Not everything is entirely clear from the final statement, but it seems that while upholding the unity, in reality, it just managed to reach the division of the state. All, however, what we discuss here, is not the final resolution, as discussions on 25 September will continue, and all parties also wish to Turkey and Egypt to accept the deal officially. So the match is not over, but at least there is a very promising result that the Libyan camps want unity and want to work for that.

What was announced is that all major ports in the state will be united to prevent rival ministries and ministers, and these along with the oil revenues will be shared based on the population under their respective control. The state will be led by the Presidential Council, in which, just like the al-Ṣuhayrāt format, participation will be shared between Tripoli and Ṭubruq. The Libyan Federal Bank was also agreed to be held united as the only financial authority in the state, but its final place will be agreed upon later. What is significantly different from the agreement signed in al-Ṣuhayrāt is that this time the long and troublesome matter of legality or choosing between the two camps was no touched. In short, the idea is that Libya will be kept together, positions will be filled by both camps, and there will be a process from the very basic levels to unite the institutions of the state. After long debates and a practical war, in which both sides tried to liquidate the other, this is indeed a breakthrough. Especially that it happened without the former main leaders. But that might just be the weak spot of the agreement.

Where it can go very wrong

It should be understood that the Būznīqa Agreement is not a solution, but the first step in a process promising solution. It is more of a general understanding on the principles, rather than comprehensive peace accords. But there is a huge amount of pending questions, which are not addressed. And if on 25 September they will not be solved, this might collapse faster than the deal cut in al-Ṣuhayrāt. There is no word on uniting the military institutions. While in theory both political camps can stay functioning, being a practical authority in given parts of the country, and they should in time unite, there is no mention of elections. No agreement was reached on the foreign interference either by Egypt, or Turkey or about the international agreements these rival camps signed in the name of the whole country. And most importantly, not only the political, but even the military leaders were not part of the process, and they seem to disagree with the deal.

If they are not forced to this deal than noting practical will come out of it. But only the supporting powers behind them can enforce an agreement upon them, while Turkey and Egypt don’t seem to be able to agree. So the main deadlock is still not broken. But the positive side of it that the lower political ranks started to directly negotiate, possibly even in the expense of their own respective leaders.

The weakest point of all is that no timeline was set. So all these agreements are not known how long will take. That, however, hopefully, can still be solved in the next round.

Why the deadlock?

Looking at the picture from where we left off in July, it seems almost surprising why this dialogue both in Būznīqa and in Cairo was held at all, and how could Egypt and Turkey allow this to happen. There are very serious internal and regional reasons for that.

The deadlock was reached in late July when after the Egyptian warnings and war preparations the al-Wifāq’s army practically stopped at the outskirts of Sirt, the very city Egypt outlined as the “red line”. At this very point, both Turkey and Egypt had other matters to attend to.

As for Turkey, the quarrel with Greece and France is still not over and Ankara is engaged in a bitter race for the maritime territories in the Eastern Mediterranean around Cyprus and some Greek islands. Though the EU did not put all its weight behind Greece warnings were sent to Turkey that if it does not stop its activities serious sanctions will come. Erdoğan seems to defy these threats, but simply the Turkish economy is not in a state it could afford such an economic war. Turkey also increased its activities both in Syria and Iraq, moving in troops and conducting areal strikes in Iraq. The latter is specifically serious, as on 11 August a Turkish drone attack in Erbil province strikes a meeting between Kurdish military leaders and Iraqi border guards, which killed two high ranking Iraqi army officers. And in Syria, another operation is on the horizon in Idlib, which the Russians seem not to keen to prevent. Suddenly it seemed the Turkish capacities were desperately overstretched when the Emirati-Israeli deal was cut. Which needs reconsideration in Ankara. The Emirati-Israeli deal, which soon will be finalized, means that the Emirati-Saudi-Egyptian camp, its main rival now acquires direct Israeli support, at least to some degree. That already prompted serious negotiations with Iran, the other main target of the Emirati-Israeli deal.

In light of the ongoing struggle with France and Greece on one hand, and the regional shift on the other, Libya suddenly became of secondary importance. Especially that the prime objectives, the stabilization of the al-Wifāq and some oil resources were sufficiently reached.

As for Egypt, similar considerations shifted priorities. Even before the dispute with Ethiopia was important, and negotiations seem to favor Cairo now. But here as well, the Emirati-Israeli deal needed attention. As we saw, Egypt is very interested to include more Arab states in the deal, especially Sudan. Such a shift will increase the Emirati and American support and can be a winning card against Turkey in the long run. Also, the main objective was reached, as the forces of the al-Wifāq government and the Turkish support troops did not cross the mentioned “red line”.

So both parties “agreed” to reach a practical ceasefire, until they can considerably change the equation for their own favor.

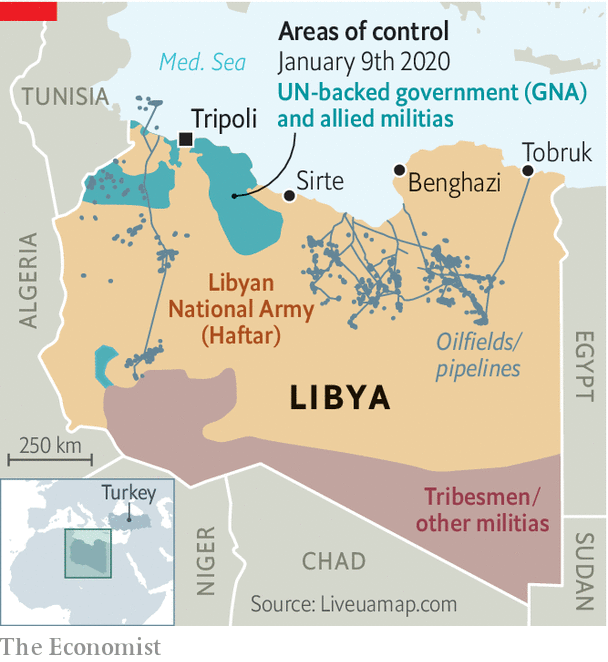

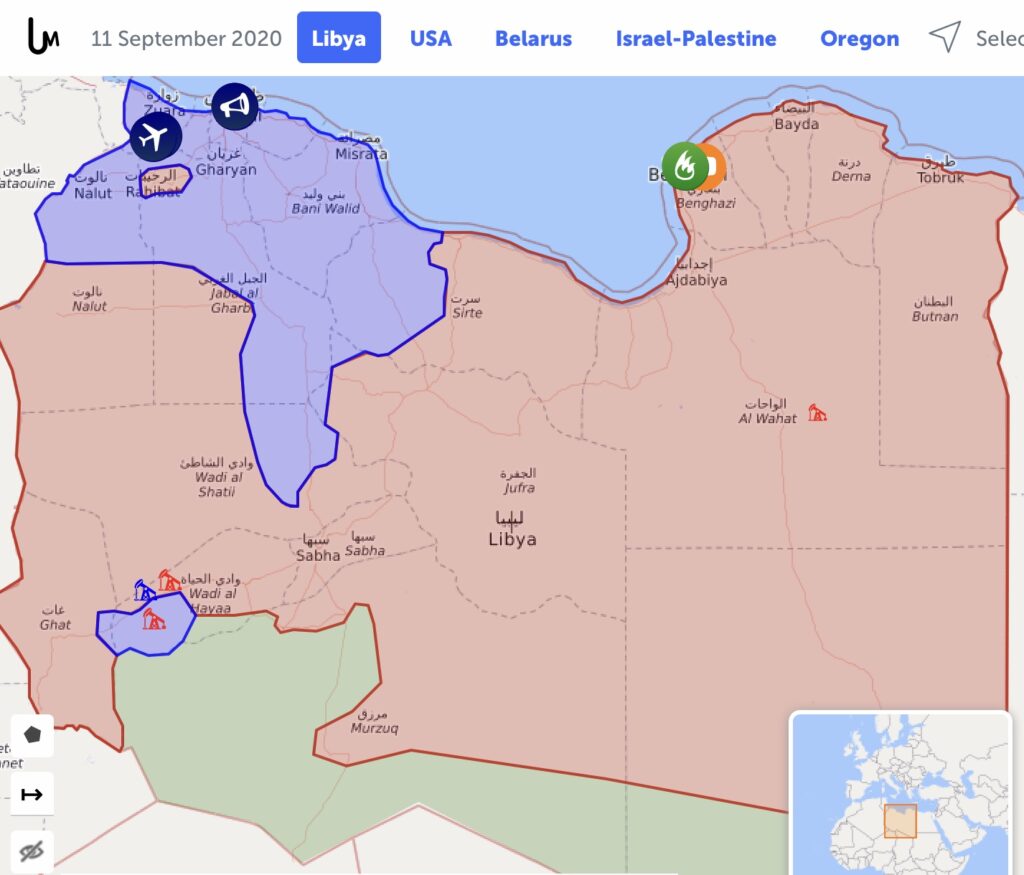

Internally, however, realities prompted negotiations. If we look at the map where the military fronts were at the beginning of the year and where they stood after the Turkish intervention, it is clear that Ḥaftar and the government behind him suffered a serious defeat.

Their collapse was only prevented with Russian arms, and by Egyptian threats of war. The futility of the struggle showed that they cannot take Tripoli against Turkish support.

After the al-Wifāq reached most of its direct military targets in July and Turkey was ready to give even more support it could have celebrated victory. But on 23 August massive protest broke out in Tripoli against the al-Wifāq government, and the protestors specifically demanded the ouster of al-Sarrāğ. These reached a level that on 28 August as-Sarrāğ had to sack his Minister of Interior Fatḥī Bāšāġā for excesses against the protestors. The al-Wifāq claimed that third party elements and conspirators opened fire, not the forces of the government, which might be true, but it was clear that regardless of the military achievement the unity government has a very fragile control over its own territories.

Both camps, especially the lower ranks came to realize that they cannot overcome the other, but their reliance on their foreign supporters is suffocating. Deals are cut by their own leaders on their own expenses, which seem only to grow. That is the very likely reason why they started open discussions behind the back of their leaders. And it is very noticeable that though the Būznīqa Agreement lack specifics, it very openly condemns corruption in several points. This signals a very serious dissatisfaction by the Libyan political class on both sides of the country with their own leadership.

Towards peace or war?

In theory, the Būznīqa Agreement, specifically the process behind it may usher in the collapse of the current Libyan political class and pave the way from unity from the bottom up. However, any final solution demands consensus between the three biggest rivals in the Libyan front, Turkey, Egypt, and France.

The Libyan dialogue is very promising, but it is also very fragile, as most specifics are not yet agreed upon. As long as the main foreign powers are engaged with other matters this move for unity can proceed. But if they solve their problems, or to the contrary, their confrontation in other fronts reaches a deadlock, they might start their bid once again in Libya.

It is clear that Libyans do want to end the war and despite many assessments contrary there is still hope for unity. Libya as a whole is still not dead. But there is just utterly little power left in the hands of the Libyans in this overwhelming regional wrestle. And unlike the Syrian state, the Libyans have way little power to control their own fate.