With the last American soldier leaving Afghanistan on 31 August the US ended its longest military engagement. Though the world mocks him now and acts appalled President Joe Biden considers this withdrawal “an exceptional success”. Which is true, just not in a way most would be willing to admit. After 20 years of war, building up a military bridgehead on the doorsteps of the most direct rivals and putting together a government to facilitate this Washington left the country to its perceived enemies. An enemy which, as we saw last week, not that obvious, given the very same Ṭālebān leader, Mullā ‘Abd al-Ġanī Barādar was supposed to be the next Prime Minister, whom the the Americans pulled out from a Pakistani prison and propped up to be the next leader of Afghanistan. By eventually “only” becoming Deputy Prime Minister the prognoses did not really fail.

With this the Americans left Afghanistan in the hands of a terrorist organization they went to war against 20 years ago. But now it is strengthened by modern American arms and perfectly trained troops, and run by a leadership much more acceptable and inclusive than before. That is not just a bad omen for Afghanistan itself, but is a liability for all of its neighbors despite the enthusiasm to turn the Ṭālebān into a useful ally by all sides. Despite the international reactions strangely accepting this movement at the head of a country this still means chaos for Afghanistan and is not a very tempting scenario for the Americans’ withdrawal from any county.

This lesson is not just about Afghanistan. Or more accurately, not anymore. There are other countries as well, where there is American military presence on shaky grounds, all result of the so called “Arab Spring” and with it the Western meddling to change the face of the Middle East. On the top of the list there is Iraq, and even more so Syria.

Now all eyes in the region are on Iraq, which a year ago was in deep political turmoil. The situation seems to be under control since Prime Minister Muṣṭafā al-Kāẓimī took office. He managed to ease the internal pressure and for the time being American-Iranian proxy struggle eased. Nonetheless elections are coming up, in which the pivotal questions are the American withdrawal, the composition of the new government and where its loyalties will lie, and the future role of Iraq.

Muṣṭafā al-Kāẓimī recently held extensive talks in Washington about the withdrawal and the future nature of relations, which yielded a provisional deadline of 31 December 2021 for a full withdrawal. He also took efforts to gather allies with Jordan and Egypt on the one hand, and with the recent Baghdad Summit on the other. Which had a significant country missing.

Will Iraq be the next country the American troops leave behind? What will that mean for Iraq? Will the Afghan scenario repeat itself, or Iraq might finally see a reestablished position? And what would that mean to Syria and the number of Kurdish projects the Americans are still running? How does Iraq tries to prevent yet another chaotic pullout?

Deep internal divisions

Iraq is indeed fundamentally different from Afghanistan. Not just ethnically, in its religious and ideological composition, but in every sense of the word. It is very important, however, that while in Afghanistan there were practically only two political alternatives, an incapable, corrupt and failing government and the Ṭālebān, there are many political players in Iraq.

Most political groups seem to agree today that the Americans must leave, yet the speed of this is much debated. That is because the main question after the pullout is still not answered: What will happen the next day? Will Iraq become a full member of the “Axis of Resistance” with Iran, Syria and Lebanon, which certain sides consider falling under Iranian vassalage? What will happen, if the American pullout is followed by the reemergence of Dā‘iš following the Afghan-Ṭālebān script? Will the events of 2014 repeat themselves? How will that effect the Turkish military presence in the north, especially if they refuse to leave? Or might just the opposite happen by Baghdad falling under the influence of the Turkish-Qatari axis? Can there be a counterweight to this other than Iran?

In light of these questions there are forces within Iraq which view the American pullout still premature, and might be more advantageous to be postponed until Dā‘iš is more crushed and the future of Iraq’s role in the region is more clear. But than again, there are just as many forces, which view the guarantee of the victory over Dā‘iš in the American pullout, as the American will stop meddling in internal affairs.

The matter is even more complicated that whatever Baghdad decides the fate of Iraq is not solely in its hands. Because the Kurdish authority in the north has considerable international support, as it was an independent entity. The American pullout would undoubtedly shift the balance between Irbil and Baghdad for the latter. But the Kurds have significant influence in the central government, meaning they also try to slow down the American withdrawal, or stop that completely. So answering these pressing questions is not easy, even if the political factions in Baghdad could come to accords with each other. Yet their squabbling never seems to end.

Apart from the – otherwise relatively united – Kurds there are four major political centers ruling Iraqi matters now. Yet to estimate their political support is rather difficult, since the last elections in May 2018 seemed clear enough, yet resulted in a deadlock and an ongoing political turmoil, after which stabile government never really formed. Still that is the best indicator to asses the possibilities.

The relative winner of the last elections was the formation led by Muqtadā aṣ-Ṣadr, the second most prominent Shiī cleric of the country. His power is based on his family’s reputation and the loyalty for it, as his father and uncle were also prominent clerics struggling against the Ṣaddām government before. Muqtadā aṣ-Ṣadr and the paramilitary troops under his influence opposed the Americans and fought a series of battles against them in the 2000s all ending with ceasefire settlements. Though his primary support base is Shiī, he is not a particular favorite of Iran perceived as self-centered and unreliable, and he also suffers from the uneasy relations with Iraq’s top Shiī cleric, the only Iraqi Grand Ayatollah ‘Alī as-Sīstānī. Muqtadā aṣ-Ṣadr is formally only the leader of the Ṣadrist Movement, but that is the leading force in the Sā’irūn Alliance, otherwise known the Alliance Marching Towards Reform. The Sā’irūn contains several other parties, even the Communist Party and has its own paramilitary muscle, but it is not the result of the war against Dā‘iš and not a main component of the Popular Mobilization, the al-Ḥašd aš-Ša‘abī. Muqtadā aṣ-Ṣadr himself is a cunning and experienced politician ready to change camps of the situation calls for it, and though after the last elections he practically lost the race to form a government at the end he managed to secure his interests with the election of Prime Minister Muṣṭafā al-Kāẓimī in May 2020. Al-Kāẓimī is officially a non-partisan, but allegedly closest to Muqtadā aṣ-Ṣadr. In July 2021 aṣ-Ṣadr announced not to participate in the upcoming elections and even had suspicious statements possible not being alive for long, but on 27 August he retracted and returned to the campaign. It is unlikely that the Sā’irūn could win the next elections alone, but by becoming once again the biggest force in the Parliament they become impossible to circumvent. And if aṣ-Ṣadr becomes the practical leader Iraq will became an unpredictable player in the region, not necessarily a close Iranian ally.

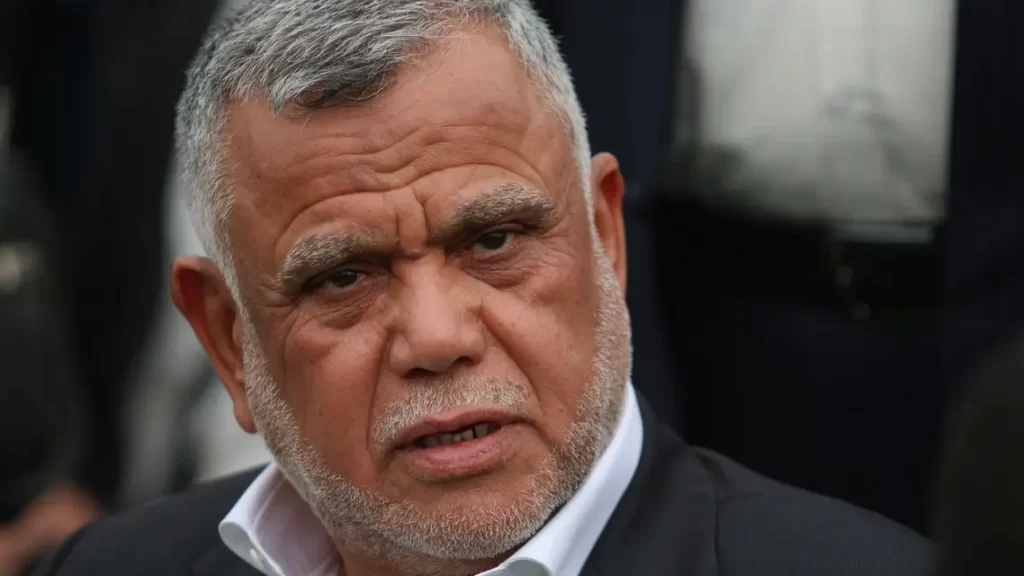

The second biggest block is the al-Fatḥ (Conquest) Alliance under the leadership of Hādī al-‘Āmirī. That formation is the political manifestation of the al-Ḥašd aš-Ša‘abī (Popular Mobilization), a loose network of paramilitary forces formed after the Iraqi forces met defeat by Dā‘iš in 2014. Since most of these groups were armed by Iranian support and are led by commanders like al-‘Āmirī, fighting on the side of Iran in the ‘80s this formation is the closest ally of Tehran and the strongest support for the idea of Iraq joining the Axis of Resistance. The al-Fatḥ came out second in the last elections, though with more tactical coordination could have won, but since then much have changed. The real leader of this formation was Abū Mahdī al-Muhandis, but he was assassinated by the Americans along with Iranian General Qāsem Soleymānī. That created huge moral support for them and shifted sentiment against the American presence, but eventually the loss of such a tactical politician really started to show. Al-‘Āmirī is a skilled military leader, but far from being a skillful politician and the al-Fatḥ still struggles to find a characteristic leading politician.

In the last year, or so factions of al-Ḥašd aš-Ša‘abī loyal to al-‘Āmirī boosted military actions against the American military presence even shelling the American embassy in Baghdad. The American withdrawal from several bases since then is largely attributed to their actions, but there was no breakthrough and the government of al-Kāẓimī managed to limit their actions shifting support for a settlement with Washington. The support for the al-Fatḥ is not what is was directly after the biggest victories against Dā‘iš, but it is still the most competent anti-terrorist force. Therefore the biggest guarantee against the resurgence of Dā‘iš after the Americans. However, they have a very limited vision for the country’s internal policies and regional relations. Their overwhelming victory is unlikely, but if they managed to come out first that would push Iraq strongly towards Tehran.

The third strongest group in the last elections was the an-Naṣr (Victory) Alliance, a partial reminiscent of the once biggest Shiī party the ad-Da‘wa Party. It is led by Ḥaydar al-‘Abādī, who was the Prime Minister of Iraq during the war against Dā‘iš being appointed after the fall of Mosul. The an-Naṣr also had great support amongst the al-Ḥašd aš-Ša‘abī factions, but it is viewed as the more conciliatory and compromising face of the movement. Al-‘Abādī was a hero of the war against Dā‘iš and much of his support emanated from the victory over the terrorist group. Yet in recent years he became viewed as a pro-American figure and his party became his personal project. His influence largely eroded in recent years and the general feelings are not for his favor. Yet his possible involvement in the next government would mean a more neutral Iraq after the American pullout.

The last power block today in Iraq is not a political party, but Prime Minister Muṣṭafā al-Kāẓimī himself. As mentioned he is closest to the Sā’irūn, but he is a non-partisan. That would make him a relatively low profile player in the next elections, however, two key features make him a real kingmaker now. First he was the head of the Iraqi intelligence for four years before becoming the Prime Minister. He managed to put the intelligence service in order after the collapse against Dā‘iš and built up most of the foreign links of the services. Therefore he has excellent international connections, better then most Iraqi politicians now, especially in the West. That is why he had the sufficient American support to lead Iraq and since he took office he managed to control the situation. The contrast is especially shocking to the two years before him, when there was no real stabile government, only squabbling. It should also not be forgotten that he negotiated the withdrawal agreement with the Americans and initiated a number of regional summits building the future foreign relations. Secondly, he is in charge of the elections. Since he proved to be possibly the most capable Prime Minister since 2001 in such a short and troubled times, it should not be surprising if he managed to stay in power even after the elections. Especially with the Sā’irūn behind him. Which is not necessarily a bad thing, as he is a conciliatory force between the political camps, and struggling for a more independent Iraq. Him staying in power would also not antagonize Iraq’s western relations, unlike the victory of the al-Ḥašd aš-Ša‘abī.

There are indications that after a good election performance by the Sā’irūn and the al-Ḥašd aš-Ša‘abī the current Prime Minister would stay in power as a compromise caretaker, but also the best possible alternative for Washington as well.

There are also formidable Sunni and Kurdish parties in central Parliament. They have way too little influence in Baghdad to win elections, still play significant role shifting balance from one power block to the other. Most of them, however, still favor American presence as a guarantee against a possible Iranian orientation.

The future of the al-Ḥašd aš-Ša‘abī

With Mosul falling to the hands of Dā‘iš and the virtual collapse of the Iraqi army with striking parallels with the collapse of the Afghan army recently, massive mobilization started within Iraq to create a force capable of pushing back the terrorist onslaught. That was the Popular Mobilization, the al-Ḥašd aš-Ša‘abī, which was largely armed and trained by Iran and led by Iranian trained war veterans. Thought the Iraqi army eventually regained its integrity the al-Ḥašd aš-Ša‘abī has a huge role in defeating Dā‘iš.

Since then, officially, the whole al-Ḥašd aš-Ša‘abī network became incorporated into the official Iraqi army. What should be pointed out, however, is that al-Ḥašd aš-Ša‘abī is big term meaning some 60 separate armed factions. Most of them are Shiī, but some are Christians, Armenians, Turkmens, or other. After the “official” incorporation some of these handed weapons over to the army and joined army units, meaning in practical terms ceased to exist. The biggest Shiī ones, however, kept their formal structure, so “incorporation” meant rebranding, official recognition that they are not entities outside of the law.

For the 2018 elections the al-Ḥašd aš-Ša‘abī – at least its most formidable component – already became a direct political entity as well. Yet because of their affiliation close to Iran and their independent actions against the Americans presence they are still labeled as a paramilitary group, or directly as Iranian mercenaries. Since there have political forces within the Parliament, the dispute around them has a significant political edge as well, both internally and internationally.

For the sake of the state integrity in the long run it would be beneficial to truly dissolve the al-Ḥašd aš-Ša‘abī within the army. That is unrealistic for now. However, with an election victory for the pro-Iranian forces and after an American pullout there would be space for that. Yet that is also why they are indispensable now.

Whatever happens, the fate of the al-Ḥašd aš-Ša‘abī is a key question, but can only be seriously addressed not to become a state within the state in the long run after a successful election. By the moderation of the still volatile Iraqi politics.

A new emerging axis?

Prime Minister Muṣṭafā al-Kāẓimī proved to be an excellent power broker within the chaotic Iraqi politics. That is largely due to his previous role as director of the intelligence, as he knows the weeks spots of most Iraqi politicians and political groups. That made him the excellent choice to negotiate the pullout with the Americans as well.

However, al-Kāẓimī is very capable on the international field too, not betting solely on either the Iranians, nor the Americans. Rather he tries to create a separate and somewhat independent role for Iraq, which policy is largely supported by the Sā’irūn behind him.

Being caught in the middle of three separate fault lines, namely the American-Iranian antagonism, the Qatari-Emirati rivalry and the Iranian-Syrian block, it is not an easy task to do. One possible way out is the slowly forming Egyptian-Jordanian-Iraqi alliance.

Such a block has historical depth. Back at the days Iraq and Jordan were both ruled by the two branches of the same royal family, and in the late ‘80s the same block facilitated Egypt’s return to the inter-Arab politics after being ostracized in 1981. There are political realities for this now as well. Egypt was a strong pillar in the Saudi-Emirati power block, but was left alone by Saudi Arabia in the al-‘Ulā Summit. Thought there has been significant steps to mend fences between Cairo and its main regional adversary Ankara, Egypt is still in a precarious situation. It is between two crisis areas, Ethiopia and Libya, and currently has few allies. Gaining partners with Jordan and Iraq, Egypt could play a significant role both in the reconciliation with Syria, and in Iraq’s future, and both cases present opportunity to find grasp on Turkey. Consequently gain bargaining chips in Libya, which is a central issue for Egypt.

Jordan right after a failed coup attempt highly tied to Saudi Arabia could see benefits in an alternative camp, which could ease the pressure from the Gulf. And in this regard the ties going strong between some Gulf countries and Israel is also a menacing security threat. Iraq and Egypt could mean potential substitute for the currently overwhelming Saudi orientation. Especially Egypt could mean a vital supporter both in investments and as an energy provider.

Finally Iraq could gain a stronger regional role apart from Iran and the Gulf. Jordan could be the bridge for Egypt to which it still has sufficiently good ties. Egypt could present a strong supporter against Turkey to end its military presence, and that could be achieved without Iranian support.

So far the groundwork for such an emerging new block is very weak and it lack ideological depth. There is no underlying common ideology. It would be only an opportunistic formation against the common threats and pressures. However, the Iraqi dependency on both the Americans and the Iranian, and the Jordanian on Saudi Arabia is at the moment so strong that there seems to be little future for this block. That does not mean, however, that they are not trying.

There has been two major tripartite summits between these states, all right before significant regional changes. The first one was held in Cairo in March 2019, which was a breakthrough, but at that time Iraq was still in a volatile internal state. This was repeated on 27 June 2021 in Baghdad, when Egyptian President as-Sīsī and Jordanian King II. ‘Abd Allah met with Prime Minister al-Kāẓimī and this was labeled at that time as the beginning of a new 30 years partnership. Apart from regional issues the agenda focused on economic, security and military cooperation, and the results are already developing fast, currently around Syria and Lebanon. The most significant result was, however, that it was only a month before the biggest international achievement for Muṣṭafā al-Kāẓimī, the Baghdad Summit, where Egypt and Jordan proved to be the strongest supporters of Iraq.

The Baghdad Summit

On 28 August 2021 the Baghdad Summit was held in the Iraqi capital. This was to serve as a major reconciliation attempt for a number of regional matters and truly managed to raise Iraq’s regional role as a strong arbiter.

A number of international agreements were signed on the conference, including long anticipated Egyptian-Qatari reconciliation, a theoretical understanding of non-interference in domestic matters, and an agreement on reopening ties with Syria. There were even rumors about a possible Syrian-Turkish meeting between the two states intelligence directors also leading toward reconciliation.

Apart the formalities not much is know about the exact agreement made behind closed doors, but right after the summit Iraqi-Jordanian-Egyptian cooperation started to help Lebanon. Yet, because it is facilitated through Syria with Iranian cooperation and tacit American approval we can assume a silent, but major breakthrough.

It is important, however, which states took part in the conference, and which leaders took part personally. The participating states and organizations were: Iraq as host, Iran, Turkey, Kuwait, Qatar, the Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Jordan and neighbors, Egypt and France as guests, the Arab League, the GCC and the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC). Iraq was represented by both the president and the Prime Minister, France by Macron, Egypt by as-Sīsī, Jordan by King II. ‘Abd Allah, Qatar by Emir Tamīm, while all others by their Foreign Ministers. This shows which were the leading states in the process, and which are those, who only “accepted” the invitation.

The two curious details were the presence of Macron, which was widely held to be a curtesy mission representing the American interests, and the absence of Syria, which was wished for by Iraq, but opposed by “a number of states”. The decision most contradicting the anticipations was Syria’s absence, but given the result it is clear that Syria was high on the agenda and by supposed Iraqi – and Iranian (?) – arbitration we can see that the path for Damascus’ re-emerge is finally agreed upon.

It shall be seen how much the Baghdad Summit truly achieved. Nonetheless it is a major achievement for Iraq proving it a strong player once again as a center of diplomacy, and for Prime Minister Muṣṭafā al-Kāẓimī himself, just ahead of the elections.

What would a pullout mean?

The answer to this question largely depends on the details of this pullout. Will the Americans leave the whole Iraq, or they stay behind in Kurdistan? Do they leave in reality, or it will be rebranded as training operations, still keeping influence? Will that be followed by a pullout from Syria as well?

The scenario most presented today is that the American combat troops will leave completely. If that means the handover of all military bases as well, the American presence in Syria will be unsustainable, as even now Northern Iraq is the logistical hub for the Americans in Eastern Syria. If the Americans would leave from both countries before Joe Biden leaves office that would mean the end of the war on Syria. Regardless of the affiliation of the next Iraqi government, such a scenario would pull Iraq closer to the Axis of Resistance, but as a minimum would improve Syrian-Iraqi economic ties. Which would be a benefit for both countries.

Iraq would, either with Syria, with Iranian support, or within a possible – and unlikely – emergence of a new Egyptian-Jordanian-Iraqi alliance regain much of its formal weight in the region. It is not only natural, but would be a stabilizing factor in the short run.

Even more importantly, with the disappearance of the American military presence the Iraqi politics still largely ruled by paramilitary groups would head towards moderation. Rebuilding could finally start.

There are, however, significant obstacles, which are so far more hidden. Tension between Baghdad and Ankara would grow. That is what al-Kāẓimī tried to prevent with the Baghdad Summit. It is unlikely that the Turkish forces would also be in a hurry to leave Northern Iraq, but if so that would be yet another factor urging Ankara to leave Syria as well.

Turkish withdrawal, however, would need certain Turkish demands to be met against the Kurds in the north. Kurdistan now is under strong American influence, thus untouchable, but complication would re-emerge between Irbil and Baghdad. So the whole Turkish presence would come within the complexities of the Turkish-Kurdish-Iraqi realities, which are now artificially suppressed by the American presence. That left unsolved could serve as fertile ground once again for militant activity.

So overall the American pullout would be beneficial for both Iraq and the region there are numerous questions to be addressed. And there are many fears that the Americans might leave behind troubles, just like in Afghanistan. Only to make ground for their return, as it happened in 2014.

That is not a distant scenario. The pullout of the combat troops might just very much mean that under the pretext of training and support operations that Americans will stay present in some Iraqi military bases, from where they keep influencing the Iraqi and regional events. And if that happens, the pullout from Syria might not happen, and the Iraqi politics will not head toward moderation, but again the confrontation will go stronger.

The significance of the next elections

After such a complex picture it is easy to understand the significance of the next elections in Iraq. If a strongly pro-Iranian government comes to power the pullout will be troubled, or might not even happen. And in such a case Iraq might return to the brink of a civil war.

If a pro-Western government came to power the pullout probably come smother, but might not be complete. Which also leads to serious troubles.

However, for two reasons the future of Iraq is not primarily determined by the elections. First, it is highly unlikely that any one political block could gain absolute majority in the Parliament. Meaning the main parties would start negotiations once again to share positions and choose a government. This leads to the second point. Most power blocks have clear foreign affiliations, meaning both all the US, Iran and regional Arab states have strong influence. So the composition of the next Iraqi government is largely influenced by the relations between Washington and Tehran. Which for the time being is easing.

For sure after the elections in October yet another set of political squabbling will start. Much of the result will depend on the regional reconciliation already started. Nonetheless, all should hope for a peaceful and calm election process with the as little turmoil as possible.