The regional race for positions is still going on. Two weeks ago we saw one end of the Middle East, the complex repositioning around Syria, which might get more complicated after the American presidential elections are over. While the race for the White House drags on for a while, the last major project Trump pushed for in the Middle East, the normalization process still goes on.

Many Gulf states watch the events with worry, in case there is a shift in Washington, but that does not stop the forces behind the normalization to continue their quest. After Sudan seems to be secured, and still held in checkmate, the Emirates pulled a very clever trick. It managed to make a favor for Morocco, which is also mentioned as one of the next possible normalizing states. And this favor might just prove big enough, as it seems to solve one of the biggest and most chronic problems of Morocco, the question of the Sahara. Or as others like to call it, the matter of Western Sahara. But will that be enough to convince Rabat to join ranks with the Emirates and normalize relations with Israel? Does the matter of the Sahara worth that much, and can actually these possible partners do enough to effectively change the equation?

This matter is not only that of Morocco, because such a change has huge implications on Algeria as well, which has been involved in the conflict for decades. Under normal circumstances Algeria would flex all its muscles to prevent such a development. But these days are hardly normal times for Algeria.

The protests, which toppled President Bū Taflīqa and his personal entourage after two-decade are still going on. President Tabbūn did his best to secure a transition to a new era, and the lead project was the amendment of the constitution with a popular referendum. This referendum was also held recently and brought less than reassuring results. More problematic that President Tabbūn was not even in the country to see out to the end, as on 28 October he was taken to Germany for medical treatment. And news are scarce from him ever since. Under such circumstances, Algeria is in a less than enviable situation, both domestically and regionally.

While there are some, who would be happy to see turmoil in Algiers that has very terrifying implications. Because if the biggest African and Arab country with the second biggest army is trouble, while Libya is still far from stabile then all neighbors have a reason to worry. And that, this is only natural by now, has much bigger connections to the whole region, as the ties reach as far as Turkey.

How did the Emirates managed to pull a brilliant tactical maneuver? And how big of a trouble is Algeria now?

The master trick

In yet another attempt to pull new Arab counties on board, after Sudan was forced into normalization the Emirates made a good diplomatic maneuver. It looked after the next possible candidate to join, and offered what it seemed to need.

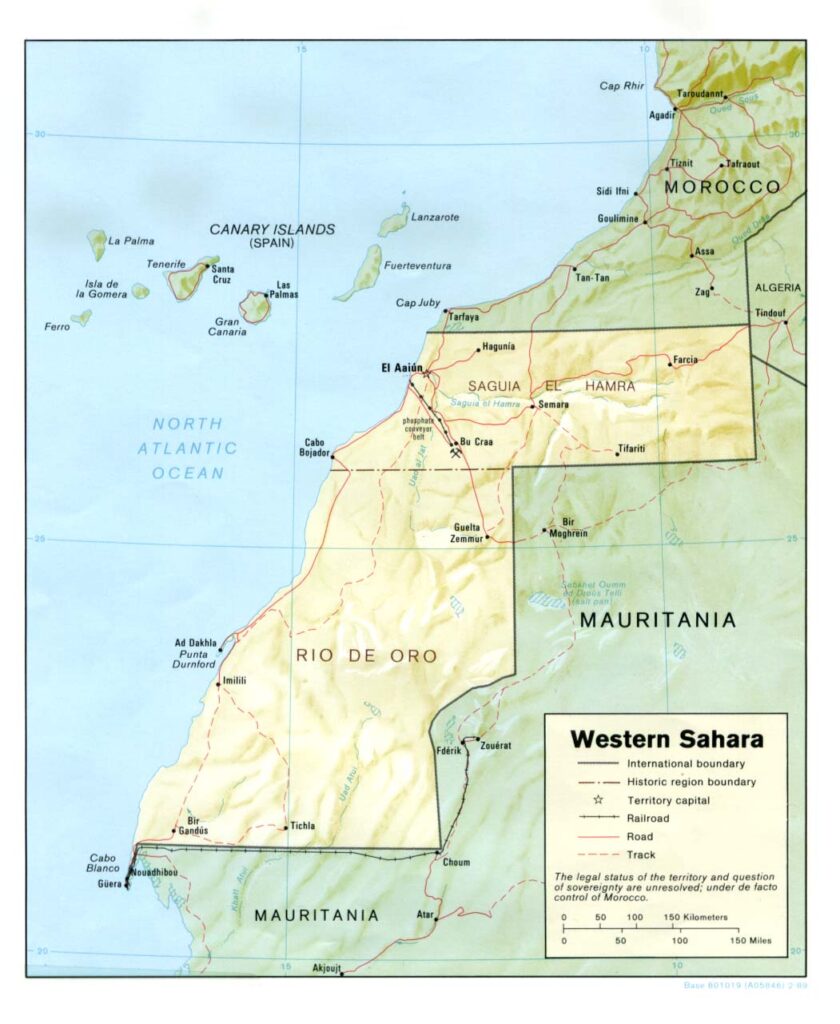

On Wednesday 4 November the UAE opened a new consulate general in the city of al-‘Ayūn in Morocco. At first, glance that is anything but remarkable, as the city with its estimated 200-250 thousand inhabitants in a very scarcely populated region seems to have little relevance. Even though al-‘Ayūn is the capital of the al-‘Ayūn – as-Sāqiya l-Ḥamrā Province – one of the 14 Moroccan provinces – the region is far from the economic heartland of Morocco with no significant Emirati interest. But al-‘Ayūn is the practical capital of the whole region that came to be known as Western Sahara. Though strictly by Moroccan point of view there is no such thing, only Sahara. The question of Western Sahara is of a long dispute and a vital issue for Morocco, as we shall see. Morocco claims the whole region as its own territory and has effective control over it, but it is a disputed matter in a number of international forums – including the U.N. – and there is a group of countries which do recognize the so-called Saḥrāwī Arabic Republic there.

The question of the Sahara is around fifty years old and even though Morocco was able to gain control over it, it never completely managed to secure legal recognition for its sovereignty over the region. The issue stayed pending, though in recent years Morocco made some efforts to reconcile and had some diplomatic success. Nonetheless, the situation is somewhat unstable, which is why the region is largely non-accessible for foreigners, and in the last year or so sporadic clashes have intensified.

And exactly this is where the UAE jumped in and opened a consulate in the region’s practical capital in full cooperation with Rabat, thus openly acknowledging Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara. Which is a clear offer that if Morocco is to join the normalization process – and Trump stays president – than in exchange Israel will support Morocco. There are reports indications that Israel is already present in this scene and pushes Washington towards this direction. And probably full American recognition can be achieved too. Just like Trump did similarly and totally illegally with Jerusalem and the Ğūlān Heights giving them as a present to Israel. That would still not mean that all legal battles are over, but Morocco practically could close the matter and exercise full military power with no fear from international reactions. At the same time its main adversary in the struggle, the Polisario organization would loose ground and probably even gain a terrorist organization label by the Americans. If that would to happen the Polisario’s main supporter, Algeria, which is already in the crosshairs for Israel for opposing the normalization would have very few choices and would have to give up this support. Thus losing a long feud between Rabat and Algiers going on for decades.

It is hard to know whether Morocco would take the offer. There are many things for it and against it. But in any case so far it appreciates the gesture and will undoubtedly exploit it if the time calls for it. So far not much happened, but the possible consequences are huge.

This is not new by Abū Zabī, as in December 2018 a similar approach was tested with Syria. At that time the Emirates reopened its embassy in Damascus as a clear sign for rapprochement and offered support against Turkey. We still don’t know what Abū Zabī asked for in return, but it did not work relations rapidly cooled. So there is a recent example that such a trick does not always work.

What is Western Sahara?

Western Sahara in large terms is the former Spanish Morocco, or the Spanish colony in Western Africa until 1975. Morocco already claimed the territory before the Spanish withdrawal in 1975 and it became a disputed area between Mauritania and Morocco after it. But even before that another organization, Polisario (Frente Polisario – Frente Popular de Liberación de Saguía el Hamra y Río de Oro) raised claim for the region and pursued the idea of an independent state. It was formed by Moroccan student with Saharan upbringing, who initially gained little support and started a sporadic guerrilla war against the Spanish. By 1973 it has become organized and started to gain territory, as the Spanish forces disintegrated and the local militia gradually deserted the Spanish for the Polisario.

In the 1975 U.N. fact finding mission it seemed clear the local population want the Spanish out and the Polisario seemed to be the most supported side on the ground. Though at that time it was still not officially recognized, it managed to gain Algerian support by 1975 – largely against Morocco – at set up headquarters in the Algerian city of Tindūf. From where after more than four decades it still operates.

In 1975 while Franco was dying and it was seriously considered that Morocco might start a war for the territory Spain decided to pull out. For that end the Madrid Accords were signed on 14 November 1975 between Spain, Morocco, and Mauritania, leaving the territory to the latter two states in a 2/3-1/3 ratio. Soon after both Moroccan and Mauritanian forces moved in, but the Polisario refused the situation. It claimed a government in exile in Tindūf and started a new guerrilla war, this time against the Moroccans and the Mauritanians. Which was not without success. In 1976 even Mauritanian capital Nouakchott was attacked, in which the Polisario’s leader and the Sahrawi Republic’s first president al-Wālī Muṣṭafā as-Sayyid got killed. The war took an especially heavy toll on Mauritania and in 1978 a coup replaced the previous leadership. The new military junta wanted to end the engagement and in August 1979 signed a peace agreement with the Polisario. In that Mauritania gave up all its claims to the region, recognized Sahrawi control over it, and that later led Nouakchott to recognize the Sahrawi Republic.

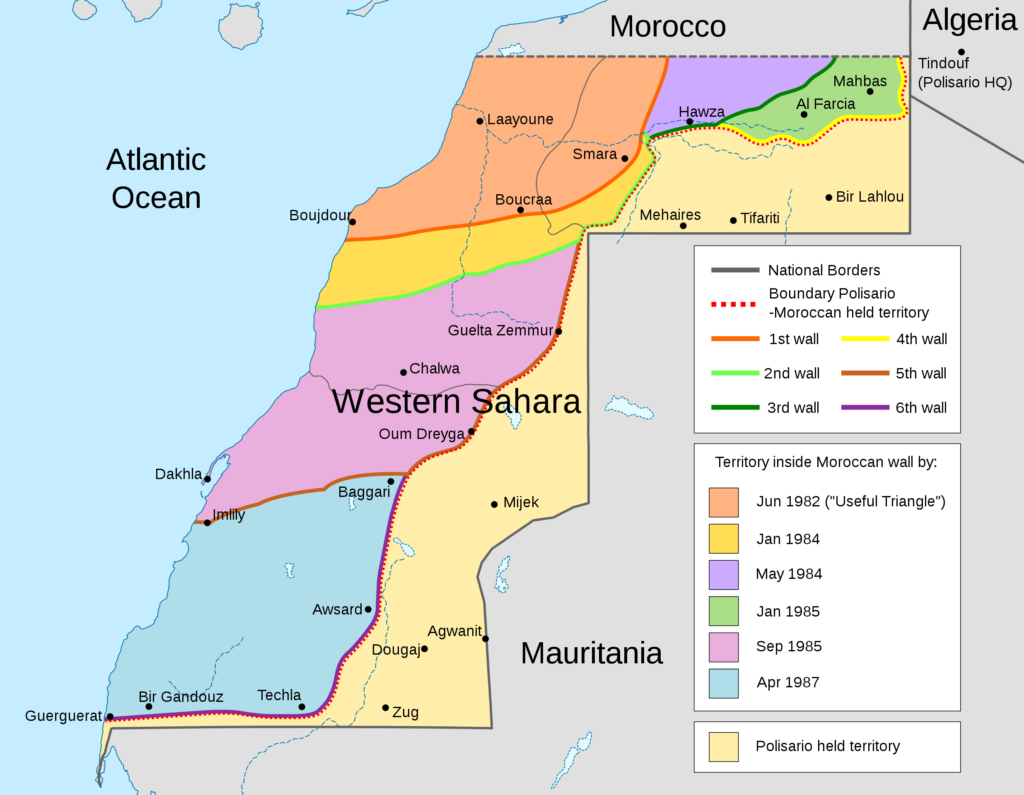

Morocco, while it had recognized Mauritanian rule as legitimate thus far, it did not recognize the Mauritania-Polisario peace deal and unilaterally occupied the territory. The war went on and was especially intense during the early ‘80s. Morocco’s response, knowing that the whole border in the middle of the desert cannot be properly defended, was to build the Moroccan Wall. A berm, a massive land structure now dividing the area with the more populated and economically useful parts within the wall under Moroccan control and the scarcely populated vast areas out under practical Polisario control. Though this did not end the war, but its intensity decreased rapidly and by the late ‘80s cracks started to appear within Polisario ranks. Many, even leading members started to leave the movement and returned to Morocco, while some by now openly support Morocco’s claim.

The stalemate and the end of the Cold War brought the sides to the negotiating table and in 1991 the Moroccan government and the Polisario under U.N. supervision signed a ceasefire and a peace deal. According to this, the ceasefire would last until a popular referendum would be held on the question of independence. In this people could decide whether they want to be part of Morocco, or want to form the independent Sahrawi Republic. While that sounds good, the U.N. left two critical points unresolved, which made the future failure predictable from the beginning. First of all the management of the elections and effective control in the region it happens was handed over to Morocco. Which was first scheduled for 1992, but was postponed many times since then. In theory, this way Morocco could stall the referendum forever. The other major problem was the status of the voters. Who could take part in the referendum?

Not much after the Moroccan and Mauritanian takeover from the Spanish large columns of local population loyal to the Polisario moved out to Tindūf, and later people from the Moroccan heartland moved in as new settlers. And that is the core of every major dispute ever since. Morocco held that the local population should vote. That does include people, who moved there in the last decades, but Rabat holds that they are originally Sahrawi people. Which is indeed very hard to deny, or prove in large numbers. The Polisario holds that only those, who were living in the region before 1975 and their descendants could vote, thus discounting many current inhabitants. That would practically mean that only the residents of the refugee camps around Tindūf could vote, but here as well it is very hard to prove origin. So both parties presented lists, which is a hotbed of manipulation and this also contributed to the current stalemate.

Since 2007 both parties offered some concessions. The Polisario offered to give guarantees to the people in the area with Moroccan citizenship to stay and keep possessions in case after the referendum an independent state would come to be. On the other hand, Morocco offered to grant autonomy to the region and refugees could return. Thus achieving the aspirations of both parties to a certain limit, which would be a healthy compromise. A year ago Moroccan king VI. Muḥammad openly suggested this solution thus making it official policy.

Though the war in the ‘70s and the ‘80s as many times fierce, since the late ‘80s it largely toned down. Clashes do happen occasionally, in recent months more than before, but it slows, as it is continued on international forums, including the U.N. That is possible largely to the fact that tough Polisario never had any major direct supporter behind it beyond Algeria and Libya, some 45 countries recognize the Sahrawi Republic. It has an elected legislature in Tindūf, 5 representatives in the Pan-African Parliament as an African Union member state, and even a legal representative in the U.N.

But it never had major military and financial supporters other than Libya and Algeria. Which made it completely dependent on Algeria, for which it just one reason that practically the whole Polisario organization is on Algerian soil. As result, Polisario is seen by many as a pawn in Algier’s hands and indeed the two are hardly separable.

Algeria has a curious relation with the whole Western Sahara matter. Officially it refuses to be part of the dispute, only supports Polisario as the legal representative of the people. But the thing is that Algeria and Morocco have a very troubled relationship from the very beginning of their independence. This lead to an early war in the ‘60s, and a still ongoing rivalry, which was only exacerbated during the Cold War, as the two countries chose opposing sides. It is probable that the matter of Western Sahara was initially a bargaining chip for Algerian President Bū Madyān when it started, but have become a deadlock and a matter of pride for the Algerian establishment. In troubled times it served on many occasions as an ideal tool to vent some steam while losing it would be somewhat shameful.

That is exactly why this is a big development. If Morocco takes the Emirati offer – whatever that is in full details – could finally enforce a settlement and put an end to the matter. Which by now would be a great achievement. After all the sacrifices made Morocco cannot let the Sahara go, as such a step would shake the foundations of the monarchy. Letting the matter go for Algeria would not be a problem officially, but very much so practically, as something would have to be done with the Polisario. And after all the decades of efforts, which costed Algeria as well very much, would end up nothing. It is especially worrisome that this would be made in the price of a Moroccan-Israeli rapprochement, which in theory could mean the appearance of Israel on the Algerian borders. Now in concept, that blow could be absorbed if there was a slightly acceptable settlement and stable leadership in Algiers. Sadly, there seems to be no offer, and the current situation in Algiers is very precarious. That is why many in Algeria worry now, and possibly that is why both skirmishes and rhetoric recently heated up again.

In road to a new Algeria.

Ever since President Bū Taflīqa tried to run for a fifth term in office in March 2019 a massive wave of protests shook the country. The protests, the by now called Ḥirāk (Mobilization) not only prevented Bū Taflīqa to run again but expressed such discontent about the whole system that toppled the leadership. Bū Taflīqa had to leave office, most of his close advisors were put into jail and the upper layer of the entire military-security-entrepreneur structure was removed. Through this process, the reshuffling of the army leaders has started before that.

With the last leadership gone and the security apparatus partially reshuffled army chief of staff Aḥmad Qā’id Ṣāliḥ became the practical leader of the country. His last major deed was, however, that he kept the country together just as long as the new elections could be held in November 2019. The elections attracted heavy criticism, as practically all presidential candidates were from the same poll of the previous party elite, but at the end ‘Abd al-Mağīd Tabbūn was elected and – though bitterly – accepted. Only a month after the elections, however, Algeria’s strong man Aḥmad Qā’id Ṣāliḥ died on 23 December 2019. His successor is Sa‘īd Šanqrīḥa, an equally strong and determined army man, though already 75 years old. Soon enough, while the new order of things was not even established, a mild but escalating rivalry started between President Tabbūn – age 74 -, his Prime Minister ‘Abd al-‘Azīz Ğarrād – age 64 – and Army Chief Šanqrīḥa, which led not only to the expulsion of the former leading members of the state but also to massive purges in the armed forces. Which was already going on before the fall of Bū Taflīqa. So while the new leaders are establishing themselves they lead a campaign that temporarily weakens the most coherent force in the country, the armed forces.

In such a situation, especially if the president is an old party politician, the strategy for consolidation was threefold. First the removal of the whole previous president’s staff and entourage. Which happened. Secondly playing every possible well-known theme of the country and of national sensitivities to derail attention. The coronavirus certainly worked in favor of the government, though Algeria’s statistics in this regard are generally very good. Returning the fallen heroes resisting the French colonialism and strong rhetoric against France certainly worked in this way. Trying to reassert a strong regional role was also attempted. First strongly backing Syria’s return to the Arab League than playing a mediator role in the Libyan crisis. Both attempts largely failed, as about Syria Algeria – or the whole Arab world at this point – has very little power, while the Libyan mediation was snatched by rival Morocco. And of course, amongst these topics, Western Sahara could not have been left out, and Tabbūn picket that up as well. And thirdly there was the rewriting of the constitution to make a legal basis for the transition. That was one of the main vows of Tabbūn in his campaign. To propose major changes in the constitution directly in response to the protests, hold a referendum on it, and arrange new presidential elections based on it.

The final version aims to limit the powers of the president by sharing his powers largely with the Prime Minister and limiting his terms to two. Including a number of executive and parliamentary changes it is a relatively large basket, but largely the same system.

On 10 September the Algerian Parliament accepted the amendment, which could then go to referendum. The representatives had only days to see the final version, it was not discussed in an open session, which caused heavy criticism by the opposition parties. Needless to say that it made little impression on the protests, but at least within the conditions created by the Corona pandemic that could have been largely disregarded. But the smooth acceptance was still a victory of Prime Minister Ğarrād. Even more so than for Tabbūn, as it was to consolidate the president’s position, it was largely Ğarrād’s script, and in the power-sharing, his influence could grow.

The final referendum was scheduled for 1 November and was indeed started on 31 October in the distant southern provinces. The first day brought only 11% participation, and overall it arrived at barely 24%. And it got almost 67% approval. On 3 November the Parliament accepted the result and considered it a success. All criticism about the low turnout was rejected, as such a thing happens in many countries and the law does not put a limit of acceptance to the referendum.

But that was a clear sign of trouble, even before rumors started to spread about massive fraud even highly increasing the numbers. Even if that is not the case, the message is clear that there was no major enthusiasm for the new draft. And what is worse, it hardly matters at his point. Because problems might have grown much bigger, as the president could not even attend the referendum campaign nor the celebration after it.

Is Tabbūn in danger?

On 28 October President Abd al-Mağid Tabbūn was taken to the hospital in Germany, officially for a deep examination. His status was reported stabile and completely fine, but it took days, after widespread speculation, to be officially acknowledged that President Tabbūn got infected by the Coronavirus. Officially Tabbūn did return on 4 November but have not appeared in public ever since he fell ill in late October.

Tabbūn at the age of 74 and being a chain smoker all his life is particularly in danger, and there are fears that even if he did survive and can recover, he will be practically incapacitated. Which is indeed a very bad omen for Algeria at this time. Right at the doorstep of his lead project, the constitutional reform, with the weak results it had anyways, Algiers might have returned to before the protests. It looks as once again the state would have a paralyzed president with all power in the hands of an equally aging arm chief and the power-hungry Prime Minister racing for influence.

It was already hard to keep the integrity of the state apparatus together with Tabbūn, but if he dies now the whole process has started again. Yet if he stays alive, but incapacitated is even worse, because that paralyzes the state. Right at the time, when the normalization, a possible change in the White House and a possible Morocco-Emirates(-Israel?) alliance all prompt swift responses.

The stakes are high, because the army is divided by the recent purges, and activity along the border, just like that of the Polisario increases. If there was to be a meltdown in Algeria after Tabbūn the country could fell back to the dark state of the ‘90s. With that and Libya still not being stable militancy could spread very fast to Tunisia – for which there are signs already – and to the Sahara.

Of course on one hand the Emirates and Israel would be happy to see chaos in Algeria. A major opposer of the normalization would fall, and Turkey would loose a strong ally in the North African scene. In addition, they could get Morocco behind them, which after occupied Bahrain and the cornered Sudan would be the first considerable diplomatic victory. But Morocco is understandably cautious for the time being. Putting an end to the conflict would be a major achievement, but if that triggers chaos in Algeria that can spread to the Sahara, or even directly to Morocco. In that sense, the stability of Algeria is Moroccan national interest.

Much of the deliberations on the Emirati deal, however, rests upon the final result of the American elections. If Trump manages to stay in power then the normalization will go on under Jared Kushner will full force, and with all likelihood Morocco will take the offer, wherever it leads it. If Biden wins, then all bets are off, and there will be some time until the new policy becomes clear.

And it already flared up

Barely a week has passed by since the Emirates opened its consulate in al-‘Ayūn and the situation already became tense. After sporadic incidents along the transport route between Morocco and Mauritania, last week clashes broke out at the al-Gargarāt (by the French speeding Guerguerat) border crossing.

Al-Gargarāt is deep within the area Morocco controls in the Sahara and theoretically should be a safe zone, but both skirmishes and activists managed to close the border crossing for some 20 days and the Polisario vowed to keep it closed. This caused an already a huge surge in commodity prices in Mauritania, which led Nouakchott to send new army detachments to the border.

On 11 November the Moroccan army also sent reinforcements and launched a limited military operation. Days later it was declared by Rabat that the border crossing is open and safe. For the moment the situation is under control, but the indications are clear that something is coming. The situation might flare up once again, which is a particularly bad sign if Algeria feels itself surrounded. Which is the case in many ways.