By mid January there were already some 40 registered candidates for this year’s Algerian presidential election. Most of them are independents, or at least announced as such, but the big question still stayed open. Whom would the ruling parties, the four party coalition lead by former state-party FLN run for the presidency? Have they finally found the suitable next leader of the country, or would they risk even a fifth term for the aging president, ’Abd al-‘Azīz Bū Taflīqa? The answer came on 03 February 2019, when the president was announced to be a candidate as a “man of consent”. And right away the state-run media, or those close to the government started vitriolic attacks on the opponents. This decision, to run Bū Taflīqa for another five years, seems to be ridiculous. Regardless of his undeniable deeds as former Minister of Foreign Affairs, president since 1999 and one of the last active figures of the war of independence, even in 2014 he was in an extremely bad physical state. So poor was his condition, that many guessed he would not live to see the end of his fourth term, and he was only supported by the almighty army, so they could decide among themselves who would come after him. Now it seems five years gone and no decision was made. So far that would be embarrassing internally. But last week, Friday 22 February, after almost three decades the Algerian streets came to life once again filled with politics as major protests erupted renouncing a possible fifth term.

So far the sycophants of the government responded skillfully saying that the protests and their peaceful nature prove, that Algeria is a democratic country. The army promised to stay neutral, and government reaffirmed the president’s candidacy, and even though the protests are still ongoing, there is considerable restraint from both sides. Which is very fortunate as no one with good intentions wish to see another “Arab Spring”. What will happen until April is still hard to know. But why Algeria is in this state? Why does this specific election means so much to Algeria? Why is that so important for the whole region now, and even possible to Europe?

The mission of Panorama is to point out regional dynamics, far beyond internal events of a given country. This time, however, Algeria’s problem reflects a regional threat that might just shake the Middle East, and a systematic problem in the Arab world, which is not peculiar at all to Algeria.

An army state?

Algeria is usually described as a military state or a police state, where the armed forces has a thought grip on the government, even by Middle Eastern standards. These simplistic descriptions usually ignore to say, that the Algeria since 1991, but most definitely since 1999 is not that of 1978, when President Bū Madyān passed away. While more then 40 parties represented themselves in the last elections, presidential elections usually see five to ten candidates and the press is relatively free, in the last elections women gained 118 seats out of 462 in the Parliament. These numbers in fact put many European states to shame. That does not mean, that the armed forces, the so called deep state does not have immense power, but one should be careful to oversimplify social dynamics. Especially now, since these protests and the governmental response to them in fact reveal a very different story, which we would get from simplistic depictions.

The overpower of the army is unfortunately common not only in the Middle East, but in many parts of the third world. As with Algeria, the opposite would be surprising. Since this state, which was until 1962 not a dominion, but and integral part of France gained its independence in an eight years bloody war, and internal disputes at that time were settled by force, not by negotiations. The army, which practically carved the new state out of France, stood behind all major changes until 1999. Behind the takeover of Bin Balla in 1963, the putsch of Bū Madyān in 1965 and his presidency until 1978, the election and the deposition of President Šadlī ibn Ğadīd, and the war against Islamic militancy until 1999, there was always a decision by the leading army and secret service generals. The “country of a million and a half martyrs”, is so much built on the legendary war of independence, that the army has a special place in the whole political thinking. For instance, the constitution specifically stipulates, that if a presidential candidate was born before 1942 has to prove that he took part in the war of independence, and if he was born later, that his parents did nothing against the revolution.[1] And since than, the country waged border war Morocco, has a proxy war with it Western Sahara for decades, has a – not at all unfounded – paranoia from French positions from the south, and since 2011 has a full blown terrorist war in neighboring Libya. Under these circumstances it is easy to see, that the army not only had to found the country, but was never really under pressure to leave power to the civilians. Gradually a tacit partnership came to exist between the armed forces, the political circles in the ruling party, itself created by the army, the small entrepreneur class emanating from it. Since Algeria was and in many ways still is a socialist country, where the state was the economy’s driving force, consequently the real governing power was even more fused together.[2]

Bū Taflīqa, born in 1937, fits this pattern perfectly. He joined the Algerian Liberation Army in 1956 against the French, where he served until independence was achieved. He met his later mentor Bū Madyān during these years in the army and the two stayed close. Since 1962, after a little interval, he served as Minister of Foreign Affairs until 1978, making him Bū Madyān’s top diplomat and one of his closest aids. When Bū Madyān died, he was already the top candidate to fill his place, but by compromise the generals voted for another officer, a weaker character, Šadlī ibn Ğadīd. He slowly faded into obscurity until the mid ‘90’s, when after 1991 Algeria was hit by Islamist insurrection.

The main problem was, that after the oil boom and the firm state control of Bū Madyān in the ‘70’s, the weaker character of ibn Ğadīd and the falling revenues presented social instability. The response was a general political reform process, at least in the facade, to move the state away from a one-party system and create bigger social grassroots for the parties, which were generally weak. This was in fact so successful, the in the first ever free elections in 1991 the so far unthinkable happened in the socialist country, Islamism won the first round. The response to the possible complete meltdown of the system was the nullification of elections and direct military control. The army, however, seeing the issue as a strictly security matter, could not solve the crisis. The solution only came with the compromise on a person, who had already proven his worth and enjoyed considerable popular respect. That was Bū Taflīqa, who managed to form a compromise with the Islamist-conservative forces, and a general reconciliation program in his first term (1999-2004). While the second term (2004-2009) largely recuperated the economy. The third term (2009-2014), was already loosing paste as several factors caused problems. Most importantly his ailing health, which made him appear ever less in front of the public, but just as well the outbreak of the so called Arab Spring, the crises emanating from Libyan, Mali, Tunisia. All these presented a logical security problem, consequently the army became important. That was, however, still a popular time, when social reforms and welfare programs were still relative successful, and after 2011 – though in fear of political unrest – the infamous state of emergency was suspended. Having stopped there, especially that in 2013 he suffered a major stroke, he would have entered history almost as national hero.

Having described Bū Taflīqa’s third office as the reemergence of the military elite, however, would be misleading as they never gave up their power over immense financial resources. Much rather, they gave up direct control to a civilian leadership, which they trusted and indeed brought results. An equilibrium was formed, where three non-homogeneous power centers shared power. The first is the president and those around him. His brother Sa‘īd, his personal physician and daily caretaker. His two favorite PMs, Aḥmad Ūyaḥyā and ‘Abd al-Malik Sallāl. And his military strong man almost as old as himself, Aḥmad Qā’id Ṣāliḥ, who is Chief of Staff of Army since 2004. The second are the army camps around respective generals from different branches of the army and the intelligence services, who do not form one solid block and they are in a constant state of rivalry over influence. Some of them are or were strong supporters of the president, while some are staunch opponents. The third power center is constituted by the party elite, the loyal functionaries, who keep the machine going. This is the most elusive of all, since some theoretical oppositional parties, or leaders are very hard to pinpoint if they are not in fact part of the mechanism. Like ‘Alī bnu Filīs, who was Bū Taflīqa’s first real Prime Minister and even ran against him in 2004 in FLN support. With the more pressing circumstances since 2011 all around, it was only natural for the generals, that they are needed. The president’s mission, however, was to solve the crisis and leave a worthy legacy. He brought inner consolidation, growing economy with more responsible planning and oversight, and even improved the welfare system. Yet he – or those around him – did not wish to give back all that to the generals eventually, only to continue from where they left off in 1991. A successful legacy needed the restructuring of the army, breaking the generals. Increasingly from his second term on, he pushed more and more former army strongmen into retirement, while he flooded the officer ranks with fresh people by raising their numbers. That, however, failed to gain success as the real strongmen are usually those very retired people, who exercise their influence through informal channels. Not from office. And the new cadres eventually ended up under the wings of one these retired officers, only boosting their camps. The real dilemma, which should serve as a lesson to many countries, is how to curb the power of the officer ranks, at the same time, when security concerns are growing. That, executed properly, is a real art.

Paving the way

So how this work can, or at least was attempted to be done? By sidelining the old big sharks, which was initiated early on. The first major victory was the sidelining of Muḥammad al-‘Ammārī – Chief of Staff until 2004, died in 2012 -, which gave leverage on the army. That, was followed by the sidelining of some other prominent generals – many, like Hālid Nizzār already in retirement -, and the flooding of the army ranks with new faces. Major steps, however, were accelerated in Bū Taflīqa’s last term, when he was practically incapacitated by his health. Therefore it is only probable, that the few generals behind the president were paving the way for the 2019 elections. In 2015, almost out of the blue Muḥammad Madyān retired suddenly, who was since 1990 head of the Intelligence and Security Department (DRS – former military security, and overall intelligence agency overseeing all special operations), the practical intelligence chief Algeria during the civil war. He was the one, who reorganized the DRS and made it a very efficient, though terrifying secret service. He himself was surrounded by black legends and seldom seen, but feared even abroad. Though not much is official about his resignation, but it is very likely, that he was forced into internal exile, as soon enough in January 2016 DRS was dissolved.

The avalanche did not stop there, but really kicked in since early 2018, under the claim of fighting corruption. In June the head of state security was replaced, than in July Major-General Minād Nūba, head of National Gendarmerie was disposed. During the same time 5 major retired generals were arrested and confined to house arrest under the charges of corruption. In August the heads of first, second, and fourth military districts[3] and also the head of military security were deposed. In September the Chief of Staff of the Air Force and the Air Defence, and also the commander of the Air and Land Forces suffered the same faith. The same month witnessed the promotion of a new leader for the third army district. That unprecedented campaign practically decapitated the armed forces, the security bureaus and the paramilitary gendarmerie. While into all positions new, formerly lower ranked officers were appointed, the old ones – some only serving for some years – were forced to retirement and allegedly charged with corruption and excess of power. That would not have been all too incredible, but what was is that all these news were unofficial as only news outlets close to the government discussed it, and in November 2018 the president even pardoned 5 of them.

All that seems to be a rushed, even panicked maneuver to bring the army firmly under government control just in time of the elections and fill key positions with people more loyal to Qā’id Ṣāliḥ. It is much less likely, that the real aim was indeed the eradication of corruption, since no such trials were seen. That can indicate two things. An internal military cue either to guarantee a fifth term for Bū Taflīqa, or securing the inauguration of a new, so far unseen character. Either way, the whole process definitely brought confusion to the army, and it is doubtful how much could disturb the probably still active and influential former DRS circles.

External threats – a contradictory trend?

While the army seems to be decapitated now, in recent years there seemed to be a very different trend. Quite contrary to weakening the army, Algeria was arming itself very heavily. Even by 2009 the Algerian army became the 20th biggest globally, and the second in Africa. Its military expenditure is the region was only third after Saudi Arabia and the Emirates. By 2015 it was rumored, that Algiers already acquired Russian S-400 air defense systems, but by that time definitely had S-300.

The most significant increase, however, manifests in the navy. Already in 2008 they bought 21 modern destroyers from France. In 2011 Algiers agreed with Russia to buy two Tiger class cruisers and modernize several submarines. The same year they bought a brand new Garbaldi class helicopter carrier from Italy, for which they already had a sufficient amount of helicopters. In 2016 China delivered three newly manufactured C28 corvettes. Also, since 2011 there is a mutual defense agreement between Turkey and Algeria concentrating on the navy, and the partners agreed to jointly work of military development. So it seems, that Algiers is desperately arming itself, mostly the navy and the air defense, rapidly increasing expenditure.

That at first would not even be surprising. Since 2011 Libya became a hotbed of terrorists, who instigated the ‘Ayn Aminās terrorist attack in January 2013. Tunisia also poses a threat as it lacks stabile government since 2011, and the border area had to be closed in fair of terrorist infiltration. The Mali crisis and the increased French military presence also raises concerns, and the mass migrations also poses a threat, as among them there are many, who are now coming back from Syria, Iraq or Afghanistan. Since Algiers is – understandably and not at all unfoundedly – suspicious of France, as it might try to promote regime change, the formation of G5 anti-terror coalition under French patronage on the southern frontiers was viewed as worrisome. Under these circumstances no wonder, that Algeria is arming itself. But it is less obvious, why the navy and the air defense is boosted, since nor migrants, nor terrorists would likely to come from the air or the sea. Clearly, something as bothers the generals. After Iraq, Libya, Syria and now Venezuela, it is actually hard to blame them. Especially, that they saw it all in the ‘90s.

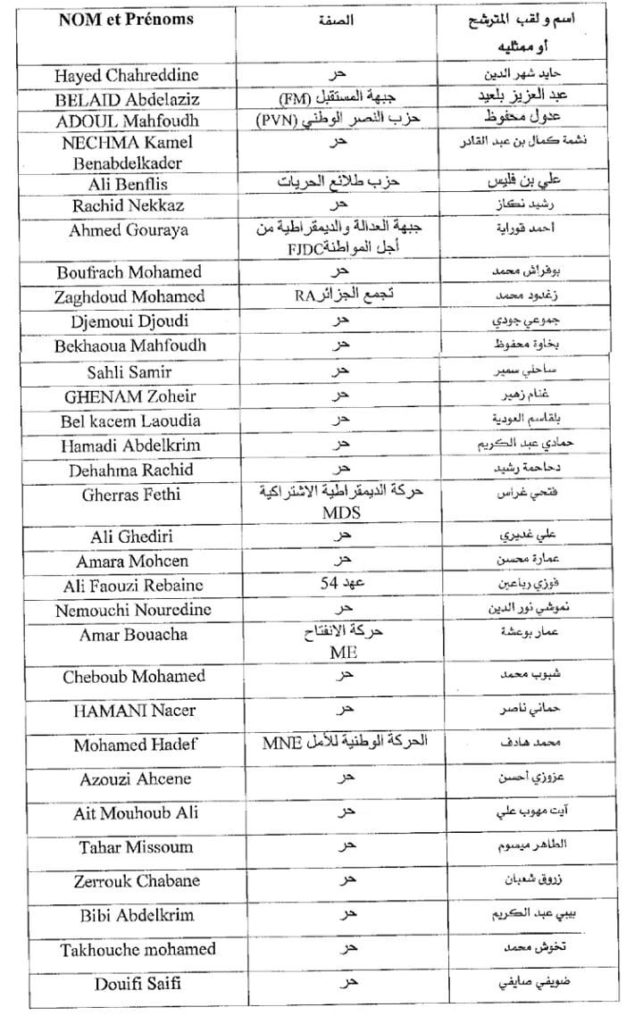

The candidates

The first semi-official list of presidential candidates came in January, which at that time still not included Bū Taflīqa, but already had some 30 names. Some, however, stick out. ‘Alī bnu Filīs (Benflis after local pronunciation) is an already known, though less likely oppositional candidate as

he himself is doubtful how far he is from the current leadership. ‘Alī Ġadīrī (Ghediri), a retired DRS officer, former head of HR is more significant. In one of his otherwise insignificant interview, he could not mention any specifics other than the general political culture should be changed. But what is interesting, that he evaded the question, whether is he a friend or a facade for General Madyān. Hinting that he is indeed the candidate of the DRS circles. That does not mean, that he would indeed like to be the next president, but as a candidate he can be a power broker for the DRS’s choice. And he is so far very active to build bridges between the candidates. ‘Abd at-Razzāq al-Maqrī is the Islamist choice, run by the Movement for the Society of Peace, which is the local branch of the Muslim Brotherhood. Though he himself is rather weak, and the war in the ‘90s ravaged standing of religious groups – though they did not officially join the FIS in the war – the reemergence of Brotherhood affiliates all over the region give credit to the fear, that Islamists might be on the rise once again. Another interesting figure is a formally independent candidate, Rašīd Nakkāz, a France born businessman. He once wanted to be a French president and run for several positions in France, even founding his own party, but after little success he gave up his French citizenship in 2014 and moved to Algeria. He did not manage to register in 2013, but did this time and he was almost crucified in state affiliated interviews. Nonetheless he is widely popular seen as an outsider and he is very active in the recent protests. Yet, it would not be surprising to see foreign interests behind him.

These candidates actually describe well the dilemma of the current Algerian leadership, whoever leads it today. Because that is surely not Bū Taflīqa anymore. Among the candidates there are former party apparatchiks, Islamists with growing region support behind them, people with possible foreign links behind them and even the re-emerging DRS. While the generals’ power is still not sure how much is broken. At the time of major security concerns all around. Whatever happens, it is very unlikely that Bū Taflīqa could survive another term, even if the leadership is reckless enough to still insist on him. With him a new generation will ascend, which does not take its moral basis from the war of independence.

A systematic problem

Seeing all these factors it is still not clear, just why Bū Taflīqa. At this age and state he would deserve to retire now, as most Algerians don’t hate, but rather pity him. They are much more insulted by those behind him, since this scene makes Algeria an international laughingstock. Just as much the president would deserve to rest now, Algerians themselves want change. Especially that it was already announced that the economy is slowing and “hard years are ahead of Algerians”. Are these newly erupted protests well founded? Surely they are not baseless. Yet at the same time, after what happened in Syria, and what happens now in Venezuela and Sudan, is the leadership paranoid to see foreign and Islamist hands – though they refrained to communicate this way – behind them? Might be so, but after the ‘90s that is not unfounded. And given the status of the whole Middle East now, and North Africa specifically, can Algeria afford internal conflicts? Quite to opposite, it needs continuity more than anything. So while the people are right to ask for something new, the leadership is also right not to allow the weakness of a new leader in such a sensitive period. There is a legitimate dilemma.

The real systematic problem is deeper and not Algeria specific. Throughout the Middle East there is a general incapability to pass on power. Since institutions are weak, much rests upon individuals and personal links. In times of major changes special – usually armed – bureaus grow robust cancerously many times paralyzing the state. In Algeria that is DRS and its predecessor, which secured the state against the French and later against the Islamist threat. In Iran the Basīğ, which was once merely one of the many revolutionary militias, and managed to survive the revolution only by being the personal vanguard of Homeīnī. In Syria no one can really understand why still the Air Force Security is the most powerful. Because once Ḥāfiẓ al-Asad ascended to presidency from the Air Force and here he had his most trusted allies. These spontaneous anomalies are understandable in a certain given time, but after decades, they serve no purpose, only become an obstacle. These institutions and the personal link among their leaders in time can create such a web of loyalties and dependencies, that it is almost impossible to any government to fight them all. Unless some cataclysm happens. But this swamp loves peace and stability, therefore can put up with any leader as long as no major challenge in anticipated.

So are Algeria politicians and generals so short sighted not to see, that an incapacitated president can not even present a facade anymore? Probably not, but while in one hand the current status quo is fine for most concerned, a change, a real new face might just change the whole equation. If that is to happen, all those concern move to lead the change and promote their candidate. The problem is now, that Bū Taflīqa lost real power before he promoted his own successor – if he ever really exercised real power -, while those around him could not agree on next leader.

Whatever happens, even if Bū Taflīqa runs and wins without general strikes erupting, fundamental changes will happen. If not from inside, saving the system, than from the outside toppling it, or even the whole state apparatus. Either way, very interesting moths are ahead of Algeria. Especially since all neighbors know, if Algeria falls now, so falls Tunisia and much of the region. So the stake is much bigger now regionally, than a simple presidential election.

[1] Constitution of the People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria (2016), Chapter 2, section 1, § 87.

[2] Werenfels, Isabelle: Managing Instability in Algeria. Elites and political change since 1995, Routledge, 2007, New York; Algeria in Transition. Reforms and Development Prospects, Aghrout, Ahmed – Bougherira, Redha M. [ed.], Routledge, 2004, New York

[3] In Algeria there are only seven military districts. Their heads are practical military governors of their designated districts.