The inner dealing of the Iraqi politics, though they are very delicate matters and no Iraqi government is in an enviable situation, became severely strained in the recent few weeks. The government of ‘Ādil ‘Abd al-Mahdī, which is already a result of some stiff competition in Iraqi politics and a compromise to prevent internal conflict, and which had to operate very cautiously to respect all sides, was caught in a very uncomfortable situation by three things. By the Bahrain Summit, which envisioned the final countdown for the Palestinian statehood, the recent escalation of conflict in the Persian Gulf, and finally by an internal matter. By mysterious explosions, or air raids on number of military positions. All these matters, especially the last one, put state and government alike ahead of a crossroad to either chose confrontation with the West, most especially the US, even if on a political level only, or for the sake of not aggravating the situation staying silent, which eventually might undermine the state. These are all hard choices and so far the Iraqi policy since 2003, and especially since the premiership of Ḥaydar al-‘Abādī, chose to actively push the Americans to the corner and try to achieve their retreat, but all that behind the curtains, so to prevent any collusion. And then the seemingly unthinkable happened, with an even more astonishing response.

The Iraqi government on 18 August 2019 ordered all coalition and specifically American planes – civilian, military and even drones – to halt any operation in Iraqi space, otherwise they will be regarded as hostile planes and will be dealt with accordingly. Knowing that by now the Iraqi Army has in its own possession – away from any American influence – very capable air defense systems that is not a light threat at all. But amazingly, the Americans not only did not react to this open threat in their usually arrogant fashion, but to the astonishment of all, peacefully complied. The reason for this unprecedented move by the Iraqi government was three – by now four – attacks on Iraqi military bases by forces so far still very mysterious. The most oblique part is that Washington took the blame for the attack of one military base, claiming the the intel they possessed was not precise and human error played a major role in the mistake. The oblique part of this confession is that most Iraqi sources did not blame the US, but the Israelis for the hits, so it would seem that Washington took something upon itself, with which in fact has not much to do with. Or does it?

Someone did indeed hit four Iraqi military bases by now, the last one on the 21 August, so even after the complete halt of American flights. Who could that be? Whether the Americans or the Israelis, what could be their purpose? And if the Israelis stand behind it, why is Baghdad so shy to reveal that, while on the other hand, what did Baghdad do, to deserve this special attention? All these put ‘Adil ‘Abd al-Mahdī is an almost unsolvable positions, where his enemies exceed his allies by far, and some of the most dangerous ones are not necessarily exterior ones.

Caught between

If there is a term precisely describing not only ‘Abd al-Mahdī himself, but his government, his political support base and Iraq itself, it is indeed the phrase caught between. The government is caught between the varying Shia factions, almost all of them the surviving remains of the once overwhelming – and still formidable – Iraqi Da‘wa Party, many of them base their support on the al-Ḥašd aš-Ša‘abī (Popular Mobilization) and its victories over Dā‘iš, the still influential Sunni groups and the growing separatist aspirations of Irbil, now openly allowing Israel to infiltrate Iraq. That collusion manifest in the regional equation, as all parties involve outer supporters and Iraq is dangerously being pulled apart by parties leaning towards foreign powers, whether they by Syrians, Turkish, Saudi, Iranian or American. That dangerous dissent already manifested in the onslaught of Dā‘iš, which is being now overcame, it would be time now to heal the old wounds. But the regional Cold War is spiraling out now, both sides trying to gain strategic possessions. Since Iraq lost much of its former power, now most actors in the region blatantly step over Baghdad in countering the other side’s moves. Therefore ‘Abd al-Mahdī has to fight for its presence in the Iraqi politics, as well as in the international arena.

As indicated in April, the last Iraqi elections were – though finally quite peaceful and transparent – very competitive between the three most powerful Shia groups, once all part of the Da‘wa Party. Ḥaydar al-‘Abādī, Prime Minister since 2014 and leading all the fights against Dā‘iš might not be a specifically charismatic leader, but he has a substantial power base, got support by liberating almost the entire country and he is the closest to the biggest religious authority in Iraq, Grand Ayatollah as-Sīstānī. Those most strive the most to obtain the blessing and support of the Grand Ayatollah, Hādī al-Āmirī and Abū Mahdī al-Muhandis, the leaders of the al-Ḥašd aš-Ša‘abī. They are immensely popular and have huge influence via the most organized armed forces in the country, but they are equally feared by many, who despise the Shia dominance. The two leader also suffer from their past once fighting on the side of Iran against their own country, which is still hard to swallow, regardless of the closeness between Baghdad and Tehran now. Ayatollah Muqatadā aṣ-Ṣadr might have inherited huge influence from his renowned family, and has the Mahdī Army behind him, made up by his family’s direct supporters, but he struggles hard to prove himself a capable religious and political leader against Grand Ayatollah as-Sīstānī. Which lately lead him to resort to distance himself and the country from the Iranian influence, and therefore approached Riyadh for support. To make matters worse, even Nūrī al-Mālikī strives hard now to reassert himself, since he got re-elected to the chairmanship of the Da‘wa Party. Since the party by now practically fell to different factions that is just a symbolic turn, but marks his ambition to return to the scene he left so ingloriously after the fall of Mosul. In this deadlock a by now non-partisan, ‘Ādil ‘Abd al-Mahdī was chosen to lead the country out of the crisis and start to rebuild Iraq after the years of war, and finally return to the point where foreign troops would finally leave the country.

That itself is not an easy task, when the most basic pillars of the state and the national spirit were shaken, but within this noticeable quagmire between the parties, which so perfectly mirror the outer influences over the country it is huge challenge. In one hand forcing the foreign troops to leave the country and not give reason for further militancy would be imperative, but to the time being the most Baghdad can hope for is to prevent a war between Washington and Tehran. Since such a war would break Iraq to pieces. The case is even more complex by the fact that economic and security concern would lead Iraq to enhance its relations with Syria and Iran, a wish supported by the most potent military and political formations, but hard to pursue once the Americans are so influential in the country. And since the Iraqi economy is highly dependent on the oil sales, it is imperative for ‘Abd al-Mahdī to prevent economic sanctions now seen against Iran.

So to achieve this, ‘Abd al-Mahdī chose a double strategy. In the regional equation he tries to find a middle ground, and while not hurting any sides, he reaches out to Egypt and Jordan. The inner side of this strategy is to increase the central authority, which one day he can pass on to someone, and for that reason tries hard to limit the al-Ḥašd aš-Ša‘abī. His vision is to fully incorporate it into the formal Iraqi Armed Forces, which would end a self active military force, and curb the influence of the most potent political rivals. The very rivals, who got disappointed by the result of the political deals following the elections and started conducting foreign policy hand in hand with Iran on their own. For that aim he issued an executive order in 1 July in this regard, which is so far almost unnoticeable. Thought the approach is a very correct one for the sake of the Iraqi state, he cannot go to far, since aggravating the case might lead to a military coup, while crushing the al-Ḥašd aš-Ša‘abī – for which he doesn’t even possess the necessary means – is a huge safety hazard, since Dā‘iš hasn’t evaporated entirely just yet.

To achieve inner stability Baghdad chose a careful path between Tehran and Washington trying not to upset any party and do favors for both. Which would be a winner strategy if the circumstances allowed him to capitalize in it. One great example was ‘Abd al-Mahdī’s attempt to renew the Americans exemptions from the sanctions on Iran, pleasing both parties at the same time. In this offered deal Iraq could still buy Iranian oil, sell it on the global market – pleasing Tehran – but giving a huge cut in this $53 billion investments and development plan to Exxon, pleasing the Americans. Thought Baghdad denied the direct connection, the practical result would still be that Iraq would be selling partially Iranian oil via an American firm, in exchange of electricity and agricultural products in one hand, and infrastructural development and capital injection on the other. That would be an ideal position for Baghdad, given the two sides were not running into a conflict.

Tehran too close

The Iranian influence in Iraq, which is noticeable all over the country by now, not only in the regular visits of high-ranking Iranian officials has very positive sides. No one should underestimate the role Iran played in the defeat of Dā‘iš after 2014, and the role it still plays not only by supporting the Iraqi Armed Forces, but also the Iraqi economy. And while Tehran now tries to stretch out in land to Syria and Lebanon, the renewed trade relations would undoubtedly boost the Iraqi economy. That is in fact very favorable for Baghdad, despite all the obvious military and strategic consequences. Thought the border crossing, mostly renewed and greatly expanded by Iranian troops, is ready for operation, the opening was halted indefinitely by the objections of the so called Syrian Democratic Forces (al-Quwwāt as-Sūriyya ad-Dīmuqrāṭiyya – Qasad). Which practically means that Washington blocked this step, but strangely Baghdad has remarkably little voice in the matter.

The other side of this coin is that this growing influence of Tehran might just come in a very high price. Dissatisfaction by Tehran – most noticeably by the Pāsdārān – towards ‘Abd al-Mahdī pushes it to resort to deal directly with the al-Ḥašd aš-Ša‘abī. That is getting ever more urgent now, as the regional competition grows between Washington and Tehran. To secure positions against both the US and Israel, but also against Turkey in Syria and Lebanon, the support – even if just the safe passage – by Iraq is imperative. And it is easy to see why. While there is much debate how much can Tehran close the Straights of Hormuz in a given war, it is seldom discussed how much Iran could hurt Americans troops in Iraq indirectly. Which right now would surely mean the loss of the next elections for Trump. It is less important for Iran what happens in Iraq in the internal matters, since investments are well on the way and that part of the Iraqi society, which looks favorable upon Iran can represent any economic interest. The important thing for Iran is in regards to Iraq is to keep it together, therefore not letting it to became a base for any foreign aggression, provide a land barrier to Syria, and by Syria to the Mediterranean. And it is a useful plus that Iraq can serve as a reserve pool for further recruitment for more volunteers, and by now the al-Ḥašd aš-Ša‘abī became a more than capable fighting force on its own, which in time might come handy in other engagements.

This pattern fits the Iranian model perfectly and not necessarily means a collusion with the central state apparatus, since this is the model used in Lebanon, where Ḥizb Allah might be a state within the state and an army separate from the state army, but it can cope well with the central government. Given the right circumstances. But Lebanon was always more of a functioning – in the good times – puzzle between the different components and has a very limited – mostly negative – experience with strong state authority. Iraq, and Syria as just the same, has a tradition of strong central state, and it is not a coincidence that now Damascus as well slowly decommissions most of the local mobilization units, to include them into the central army. That seemingly limitless support to the most zealous section of the Iraqi society, however, undermines the central government in Iraq, which is already struggling. And this model also has a safety hazard for Baghdad, a lesson bitterly learned by Dā‘iš, that the Iranian influence is something very hard to swallow for the large sections of the Iraqi society, which still vividly remembers the ‘80s. Letting al-Ḥašd aš-Ša‘abī loose is not just dangerous as it might push the country into an unwanted regional war, might even instigate it, but also it may aggravate part of the society for an open revolt.

Most unpleasant cooperation

The other main problem for Baghdad now is the American presence, which just as much attracts hatred and militancy, as many are eager to fight the Americans and take revenge for the occupation. That is a very pressing matter for any Iraqi government, since the Americans acting on their own just as well bring the country into conflicts, it otherwise wishes to avoid. Not only against Iran, but much of the American support for Qasad flows through Iraq. That is not only a problem for Baghdad as Damascus keeps complaining, but also because the most direct interest of the Iraqi state is to Syria reassert its control along the border and cut the possible movement of militants to the most volatile al-Anbār province. While the least Iraq wants is instability by its Syrian border, reopening the crossing points and continuing trade relations is very favorable. But as long as the Americans keep interfering, just like we saw with the matter of the border crossing, it is something very hard to achieve. All previous Iraqi governments since 2003 worked hard to achieve American withdrawal, which was only formally reached in 2011, when the whole region sank again in an all-out crisis. The reappearance of the American troops is just as problematic as it was before 2011, and much bad blood was caused in the war against Dā‘iš. Widespread rumors hold that they contributed to the terror organization’s spread – a thing proved in regards to Syria – and prolonged the liberation of the country by bombing Iraqi positions in a number of cases.

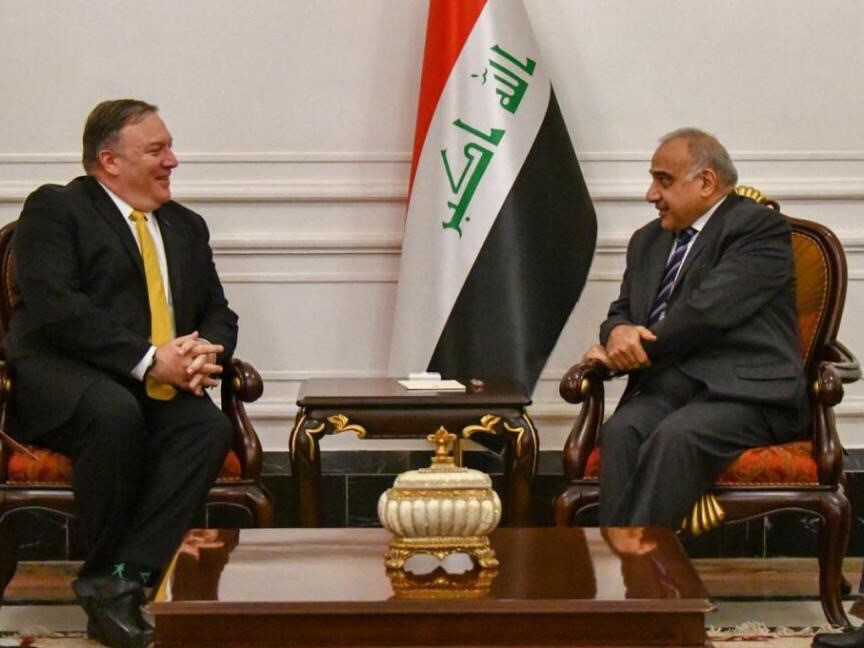

The relations between Trump and ‘Abd al-Mahdī, who’s main mission was to rebuild the central state and reassert authority, were strained from the very beginning. The Iraqi PM was still fresh in his office – since October 2018 – when Trump visited the American troops in Iraq in late December. But he did this without meeting any Iraqi officials and allegedly even without informing them forehand. That is such a serious disregard for the sovereignty of the state that it already almost caused ‘Abd al-Mahdī’s downfall. And here we are not talking about a slight diplomatic mistake, so typical of Trump, since even in the election campaign and after it he regularly expressed that he will “take the oil”. And in some of these speeches he openly scorned the Iraqi “sovereignty” as non-existent. Now it is very hard to build a smooth cooperation with a state, which openly disregard the very state leadership, which just right now tries hard to reassert itself. And in this light, it is not only very hard for ‘Abd al-Mahdī to convince the Iraqi people that he is a serious leader, but also not to see the Americans as invaders conspiring against the state.

The openly hostile attitude of Trump and his team against the closest allies of the present Iraqi government is even a bigger problem, since it keeps testing ‘Abd al-Mahdī just how much authority he can obtain, while it also undermines all his attempts to curb the zealots influence, as anti-American sentiments run high in the region. Not only by the confrontation with Iran, but also by the “deal of the century”, in which Baghdad had no choice, but to oppose it. The same thing happened, when Washington raised the idea to create an international coalition to safeguard the water traffic in the Persian Gulf, even involving Israel in it, which was again to outrageous Baghdad had to protest and refuse it.

‘Abd al-Mahdī is indeed in a very unenviable position, as the Americans – at least Trump – openly mock him – though not personally -, just like the Gulf leaders, which already made the Saudis the laughingstock of the Arab world. Yet, should he resort to the other end, seeking Iranian support, they are not any more generous to him. In a number of times Iranian officials visited the county meeting with Grand Ayatollah as-Sīstānī, or other religious authorities, but not the PM. Therefore he takes refuge in a very narrow path, doing favors for both and constantly consulting with both parties, by which trying to show an image of neutral conciliatory ground for both to sort out the main differences. But that is just not what most of the Iraqis expect from ‘Abd al-Mahdī, should they lean either way.

And the slaps kept coming

So ‘Abd al-Mahdī was already walking on very thin ice as many – more Iraqis than outsiders – wished to see him step down. There were already clear signs that regardless all his attempts, the two most hazardous “friends”, Iran and the US don’t take him seriously. While he chose the least confrontational approach possible. But more direct slaps kept coming to Baghdad signaling that the regional conflict might spiral out of control and Iraq becomes a battleground, which was ‘Abd al-Mahdī’s biggest fear from the beginning.

The first huge scandal came in mid July 2019, when an intercepted conversation between the head of operations in al-Anbār province in the Iraqi Army and CIA operatives got out to the public, revealing that they conspire against the al-Ḥašd aš-Ša‘abī, and the Americans are gathering intel on the Movement’s positions and capabilities in their military bases. Which in fact belong to the Iraqi Army. The result was the replacement of a number of army generals, the very people who should facilitate the Popular Mobilization’s incorporation into the army, and an overall inspection by the Iraqi Security Council, lead directly by the PM. The matter was made worse by fears that the Americans in fact plan to instigate a military coup – a move previously much more suspected from the Iranians – and many political factions already demanded Baghdad to cut all connections with the Americans and expel them.

The matter was still fresh, when on 19 July huge explosions happened in the Āmirlī Military Base in the north of Iraq, which is a known compound for the al-Ḥašd aš-Ša‘abī. Allegedly that killed two Iranians, but explanations kept running back and forth whether a drone hit the base, an internal explosion happened by a ground attack, or mismanagement caused the incident. The Iraqi Security Council had even more to inspect. That was followed by an other, similar incident on the 26 July in the Ašraf Military Base in Diyālā Province, which allegedly claimed the life of 40 people, most of them belonging to the Qods Forces of the Pāsdārān. Though the Iraqi officials once again kept silent, most witnesses held that it was done by unmarked fighter jets. Than on 14 August a similar incident happened in the aṣ-Ṣaqr Base in the south of the Iraqi capital. ‘Abd al-Mahdī visiting the site upheld the official storyline that this was caused not by jets, but by mismanagement. However, most people already suspected Israel to be behind all these mysterious attacks, especially the last one. Netanyahu visiting Ukraine in those days hinted, answering a journalist’s direct question that indeed Tel-Aviv is hitting Iranian positions, thought he did not admit the strikes directly. This is not possibly to be excluded easily, since the Israeli Forces regularly conduct similar atrocities in Syria, also with a total disregard for the sovereignty of that state.

The Iraqi Security Council was still investigating, but it is doubtful how much ‘Abd al-Mahdī believed the official story held even by him few days before, as he ordered all American flights to stop immediately, only to operate by special permission from his own office. Meaning by him personally. By the warning all unauthorized flights will be regarded as enemy movement and dealt with accordingly. Surprisingly, the Americans complied instantly without any objections, meaning they realized that this time the message is absolutely serious, and having failed to comply ‘Abd al-Mahdī might become incapable to stop any retaliation. But the expected result, the gradual cooling did not happen, as on 21 August yet another attack occurred, this time on the Balad Military Base in the north, also belonging to the Popular Mobilization.

The leaders of the al-Ḥašd aš-Ša‘abī obviously were unsatisfied with the government as on 21 August Abū Mahdī l-Muhandis issued a statement openly accusing the the Americans and the Israelis with these attacks. Aḥmad al-Asadī, president of the National Support Block (Tağammu‘ as-Sanad al-Waṭanī – Tasaw) belonging to al-Ḥašd aš-Ša‘abī said that this step by Israel should be understood as a war declaration. These claims were supported by the assessment of Karīm ‘Alīwī, member of the Iraqi Security Council, the same person who stood behind the spying charge in early July, who said that evidences prove that Israel stands behind all four attacks, and Tel Aviv tries to assassinate the leaders of al-Ḥašd aš-Ša‘abī. This time, however, unlike with the position of the Iraqi PM only few days ago, the Americans instantly reacted renouncing all such claims and any American complicity.

Questions and possibilities

There are many explanations for these events, however, all pose even more questions. If we suppose the Americans were behind these attacks, or if they helped the Israelis to do that would fit well with the claim in July. Not necessarily that they work on a military coup, but that they are rapidly gathering intel on al-Ḥašd aš-Ša‘abī bases. Given that now Washington is in a sensitive position in Syria, where it has to deal with a possible upcoming Turkish offensive against the Qasad it is vital to keep this support line undisturbed from Jordan to Syria via Iraq. For that aim to bog down al-Ḥašd aš-Ša‘abī with surprise hits is a logical assumption.

That raises the question that if the Israelis are involved, why are they doing this. Why are they provoking Iran and its allies in such blatant attacks? The explanation is fairly easy, since new elections are coming up in Israel very soon, as Netanyahu failed to form a new cabinet after the last one this year. Now to actually get himself elected he desperately needs to keep tensions high, so to pose himself as a capable and effective leader once again. The trick which was done before in Gaza might be done this time with hits in Syria and now Iraq, giving the image that he is fighting Iran. That is also important to facilitate the blossoming relations in the Gulf now, especially that the rift widens now between Riyadh and Abū Zabī, opening space for Tel Aviv to get involved.

Iran on curiously silent on the matter, but it is even more intriguing why the Iraqi government tries its bests to ditch the issue. Which it is ever more incapable to do with each new atrocity. This is the most puzzling matter. One possible answer comes from ‘Abd al-Mahdī’s policy to keep a balance between the two camps. Openly accusing the Americans with the hits, or even worse, with complicity in Israeli atrocities, would put him on collusion course with Washington. And from that position to achieve smooth American pull-out any time soon would be impossible. Consequently that would seal his fate. And if indeed the Americans were working on a military coup, in such a situation coup attempts would surely accelerate. But just as much, this step would play way to much to the hands of the rivals in the al-Ḥašd aš-Ša‘abī, since an official acknowledgement would give the green light for retaliation. And then all would ask why he did not act before.

Either way, the Iraqi government is in a very worrisome position, as a proxy war is looming in the horizon. ‘Abd al-Mahdī has remarkably few cards to play with, as he can not trust nor Washington nor Tehran, yet keeping good relations with both is a vital interest. Consequently, any interior forces are suspected to move against him, either to push him into a collusion course with one side, or to outright replacement.