On 20 January 2022 Thursday Dā‘iš made a sudden and laud appearance once again, as it launched an attack on the central prison of the Kurdish Qasad militia in the Syrian city of al-Ḥasaka. According to the most advertised version the terrorist organization exploded two car bombs right at the entrance of the makeshift – and heavily overcrowded- prison, a building of a technical high school originally, and stormed the building. After the initial success allegedly the terrorist managed to largely overtake the prison and free their associates within. Though they wanted to escape, soon a fierce fight broke out, into which the American forces also got involved leveling a number of buildings in the city.

The battle still rages on, so far resulting in the death of hundreds of fighters on both sides, and a lower number of civilians. The fighting is still reported to be fierce and far from over, but from the very early days expelled thousands of local families from the war torn neighborhoods.

It is peculiar scene. Al-Ḥasaka is not only a major city in Eastern Syria and one largely co-administered by the Syrian governmental forces and the American proxy Qasad (Syrian Democratic Forces) militia, but also one regularly held safe from most perils of the war in recent years. And even during the height of its power Dā‘iš never managed to take serious inroads to the city, where violence was largely characterized as power fights between the various Kurdish militiamen trying to wrest control and the Syrian government forces keeping order. This counts to be one of the most secure strongholds of Qasad – even is the city is not entirely in its hands – with roughly a dozen illegal American bases backing them up. So it is puzzling both why Dā‘iš chose to attack this city, and why this fight is still not over.

This strange event, which provoked long not scene attention by the international media, coincidence with heavy talks about America’s future in Iraq and Syria, Americans setting up oil installations for Qasad in Syria, the sudden rise of Dā‘iš also in this country and an equally sudden rise of Kurdish activity in the region. Which all adds up to a suspicion by many, as this cannot be a coincidence.

The battle for al-Ḥasaka

As said, the whole event started on 20 January with a sudden storm against the central prison of the Qasad militia. Such a scene in not entirely new. Both in Syria and Iraq Dā‘iš prisoners breaks have happened in 2019, 2020 and even in 2021. Also during the war against Syria since 2011 it happened in several occasions that entire cities, or parts of cities fell to the terrorists after they stormed the local prisons and armed the prisoners.

However, two key features are peculiar. Since Dā‘iš was largely crushed by the end of 2017, such prison breaks only happened in prisons held by Kurdish forces. No such event ever happened in any prison held by the Syrian Army, though undoubtedly the Syrian state also holds thousands of former Dā‘iš members and leaders locked up. The other interesting fact is that such events tend to coincide with major shifts in the regional equation. Which is also happening now in Eastern Syria, as tension is rising between the Syrian, the Russian and American forces.

Most previous disturbances with Dā‘iš prisoners in Syria happened in the same improvised Kurdish prison in al-Ḥasaka, which could have been a warning sign. In recent months the American forces increased their activities transporting such inmates between various prisons under their influence in Syria and Iraq, which makes it dubious how could to organization know about the size of its sympathizers in the prison, but also how could they organize such a massive attack. Nonetheless, this time, unlike all previous attempts, Dā‘iš not only attempted to free its troops from the prison, but engaged in a heavy street fighting and tried to encroach even further into the city.

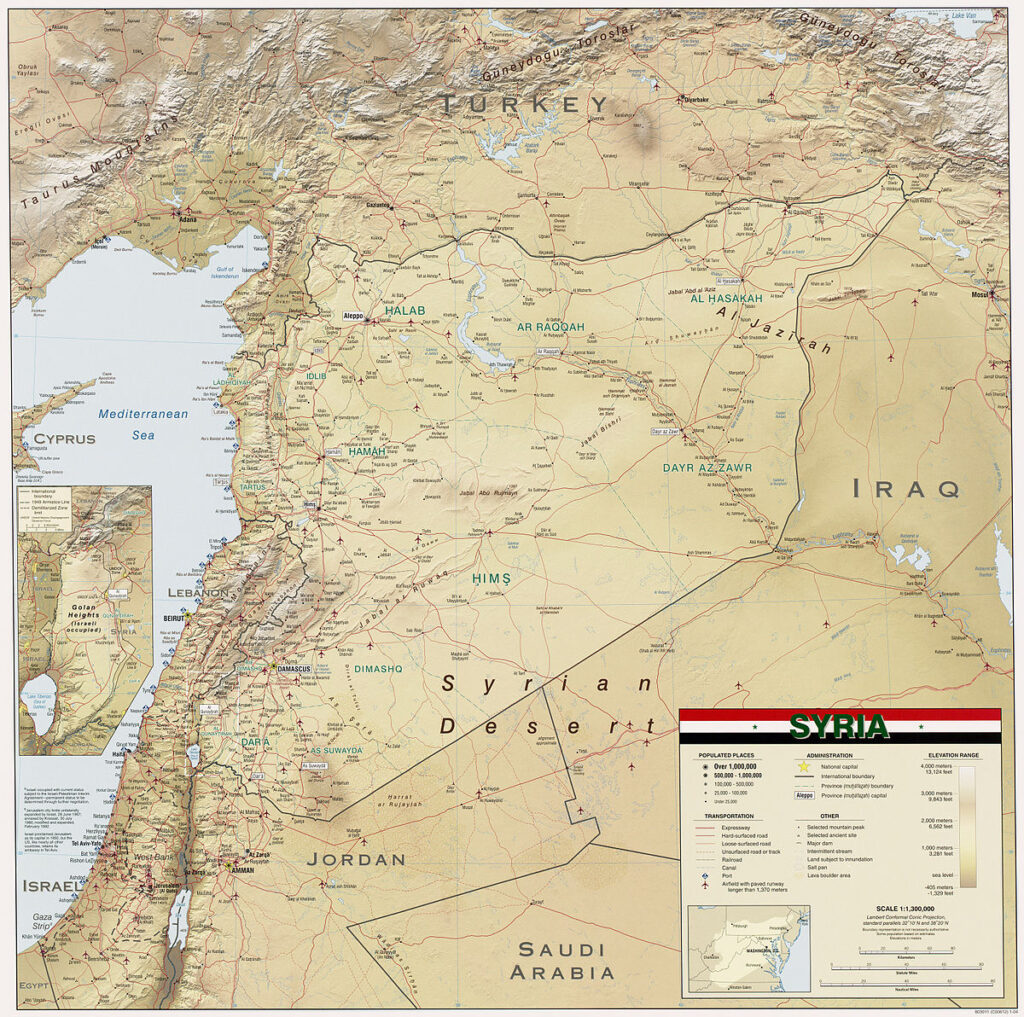

In result of the war al-Ḥasaka, capital of the province under the same name became practically divided along the Hābūr River. South of the river is largely held by Qasad, while north of the river is practically under Syrian state control. The prison in question in just south of the river, right along the former industrial complex of the city. This industrial complex in recent years was practically held in a condominium between Qasad and the Syrian state for mutual benefit, holding the central grain and fuel storage facilities. It neighbors two bigger residential quarters, az-Zuhūr and Ġuwayrān. Two areas, which saw regular clashes during the war and now the center of the war. So far the battle rages in the southern and eastern outskirts somewhat far from the hearth of the city. But as residents are heavily pushed north, the fighting also pushes along. Intentionally, or not, but forcing the Qasad troops – and the American troops directly supporting them – to take over bigger parts of the city. Especially the crucial industrial complex, which is the key in holding and servicing the city.

It is a question how long the war will last, but several matters cast a dark future over the future of the city. Rarely such a mass exodus of residents have been seen in this city. And since now it is extremely cold in Syria, this puts a huge humanitarian burden on the local administration. A burden seems to be totally disregarded by Qasad now. Also the relations between the Qasad leadership and Damascus is uneasy, just like it is between Damascus and Washington. So it is doubtful how previous arrangements can be reinstated after this battle ends. And since in several former occasions Kurdish militant formations refused to allow former residents to return to their homes, this seems to be likely scenario here as well. Which led many to suspect that the Qasad is not at all in a rush to end this fight. Much rather gambling on an ethnic cleansing, eventually moving “reliable” Kurdish elements into the city.

The role of al-Ḥasaka

Tensions in the city, just like in the whole province is not new at all. Since the fall of Dā‘iš Qasad helped the consolidation of the illegal American presence, and became the de facto security contractor for its bases. Boldened by such support in recent years Qasad steadily engaged in ethnic cleanings in rural al-Ḥasaka, forcing Arab tribes, Armenians and Assyrian to relocate. Which have invoked armed resistance by the local Arab tribes, only to be kept in bay by American intervention.

Though it is usually held that Eastern Syria is a “Kurdish region”, this is a very misleading idea. First of all, just like in 2011, in 2022 as well we have no reliable statistics about the demographics of the region. However, it is well known that Kurds even including those, who had no Syrian citizenship, never constituted a majority in the local population. Nor in the three Eastern Syrian provinces, nor in the major cities, even if there were mostly Kurdish inhabited villages. These villages, however, formed no coherent mass and the area was dotted with Arab, Assyrian, Armenian, or highly mixed towns and neighborhoods.

The war undoubtedly changed all former equations. All kinds of local residents were chased away, while Arab tribes proved to be the most resilient. Some moved back, while some were replaced by other local residents, or by Kurds from Iraq, Turkey or even Iran. This transformed democratic reality is a source of growing tension. Who will be in charge once the dust finally – if ever – settles? All this in scarcely inhabited, but economically crucial area is a cardinal question for the overall settlement for the Syrian war.

Some 80% of the Syrian oil and gas reserves – which would be alone enough for all Syrian economic needs – are here. Now mostly controlled by illegal American bases. That serves as the economic basis for the American occupation and for the future Kurdish local authority- under the Iraqi model. But Eastern Syria lacks one important piece of this equation, oil refineries. Such facilities in Syria are traditionally at the coast, far from the reach of the Kurds. However, recently the Americans started to set up an oil refinery at one of the largest oil field under Qasad management. Regardless the heavy objection by Damascus the refinery went into operation on 17 January, only days before the recent battle.

The future of this region is long in dispute. Damascus is ready to negotiate with the Qasad leadership, but not ready to allow a Iraqi style local authority, nor to accept American presence in the long run. The American game plan focuses on leaving eventually, or largely reducing the military presence, but leaving a local Kurdish semi-state behind, only to be used in any later needed event. The Kurds for now prefer the American support, but are obviously skeptical about their future, unless they gain assurances from Damascus. As this seems to be unlikely, they entered into negotiations with the Russians in Moscow. Even though in November Qasad leaders met with Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov, nothing conclusive came out of it.

So it is clear that the region is in dispute and immensely important. Now, if any game plan tries to build up a Kurdish administration of some kind – especially by the Iraqi model – Syria differs from Iraq in one central matter. In Iraq there are not only semi-homogeneous Kurdish areas, but there are major cities with clear Kurdish majority. Syria is not like that. While there are Kurdish majority villages, or smaller areas, no major city in Eastern Syria is clearly Kurdish populated. And no major city under the Qasad’s clear control. The closest to this is arguably al-Qāmišlī. Which is not only held largely by the Syrian state, but also relatively secluded from the most essential oil fields. And the city being the biggest obstacle in a theoretical mass is al-Ḥasaka in the middle of it.

In such light it is not at all unfounded to presume that the current battle is indeed for the control of this key city. If Qasad could wrest overall control over this city, it could move in Kurds from other areas into the city. And thus it could serve as the new “capital” of the imagined Syrian Kurdistan.

Such plan was envisioned before about ar-Raqqa. A city, which was also divided ethnically before the war between Kurds and Arabs. It became the de facto operation center of Dā‘iš. Once the terrorists lost the city the Kurdish militias – the forerunners of Qasad – wanted to make it as their own “capital”, but eventually lost this race by a complex set of developments.

Since Qasad lost ar-Raqqa, it became far more organized, but suffered from the lack of a major urban hub to facilitate it operations and serve as the nucleus of its economy. How clear this gambit is now shows in the Syrian “opposition” media. The outlets, like Orient Tv, which were the main outlets of the formerly Western supported terrorist factions – like an-Nuṣra or Free Syrian Army – now also openly talk about Qasad-Dā‘iš plot. Such suggestions allege that the two sides play for the same scenario, only to overtake the city. Given the fact that Qasad should be massively overpowered and that it wouldn’t be a challenge for the American troops supporting them to cut the Dā‘iš supplies, such scenarios cannot be easily dismissed. Otherwise it is hard to explain how the battle still goes on, while thousands of Dā‘iš members have already surrendered.

Whatever goes on today in al-Ḥasaka, it is a dark game. But it is not the only recent development in the region connected to this matter.

The future of Iraq

Since the last parliamentary elections in October 2021 there is still no new stabile government in Iraq. This shaky time between the two governments was chosen by Washington to pull out from Iraq, while the attacks against it bases are growing. It was a demand by a wide range of Iraqi political movements for the Americans to leave the country, which was agreed upon, but the finals details remained disputed. The demand was a complete withdrawal from all Iraqi territories, while Washington was reluctant to leave entirely and only agreed to end fighting missions.

The final deal was that the remaining American and Western troops will be restricted to only two bases and only to intelligence and training support. The matter is important, as if the Americans were to leave, or at least seriously cut back their activities in Iraq, their presence in Syria would be hard to maintain. This would indicate that soon the Americans soon leave Syria as well.

The recent steps towards Qasad make this doubtful, but the steps in Iraq even more. On 18 January, so once again days before the battle erupted in al-Ḥasaka the commanders of the so called International Coalition met with the local government of Iraqi-Kurdistan. In this meeting the Coalition, practically meaning the Americans promised renewed support for the Pešmarga, the local Kurdish militia. Officially to fight Dā‘iš in the region.

Considering the timing in regards to the situation both in Iraq and in Syria the indication is that the Western activities in the region are not about to be downscaled. Only transformed to a new strategy, in which the Kurds might play once again a pivotal role. And not only in Iraq.

What is Komala?

The many Kurdish organizations, like the PKK in Turkey, the Peshmerga in Iraq, or Qasad and its forerunner YPG in Syria are relatively well known. And despite their dubious nature and the strong cooperation between them, in some places they are viewed by the West as freedom fighter allies, while in other terrorists. Such contradiction was clear for example in 2016, when Washington clearly supported the YPG and Kurds in general in Syria, while it was well-known that this is the same network Turkey views as terrorists.

And their controversial nature is only more clear that YPG, while now treated as a key ally against extremism was from time to time a partner of the so called Free Syrian Army and its terrorist affiliates.

A less known part of this network of Kurdish militias is Komala, the hub’s Iranian branch, which has all its operation centers in Iraqi Kurdistan. Komala was formed sometime around the late ‘70s in Iran, and was active both following the clashes after the Shah’s fall and during the Iraqi-Irani war. After the war it singed a peace treaty with Tehran, but in 2016 announced to renew its armed struggle against the Iranian state. Though little is heard about them and pose no real existential threat to Iran, it is a growing organization with clear support from Iraqi-Kurdistan. Which no doubt troubles the relations between Tehran, Baghdad and Irbil.

As we saw, regardless the announcements that all American fighting forces left Iraq, Kurdistan is still a pivotal part of the American presence in the region. And therefore such branches as Komala are not to be underestimated. How strong their image is shows that in 2018 Komala became a registered organization in the U.S., while in 2021 the BBC’s Arabic channel made lengthy, as very telling documentary about the organization. Which documentary does not hide the fact at all that this is an armed group operating in Iraq against Iran.

However, Komala is one of the most clear example of the original militant and Communist ideology of many Kurdish organizations. The fact that such organizations operate clearly under a semi-state, which is key ally of the West should raise questions. Yet what we see is clear support.

Who’s militant is a “good militant”?

It is not new to see ambiguity in the West’s approach towards the Kurdish militant groups. Their image seems to be unshakenly positive, regardless of their militant nature, Communist ideology and strong personal cult around certain leaders.

Regardless the sometimes deep divisions between the groups in different areas of the Middle East, the cooperation between them seems not only stabile, but amalgamated by the constant Western support. And this support seems to be on the rise now. And not even only by the West.