After creating a seemingly broad coalition Washington and London launched a massive areal operation against Yemen on 12 January. That came only one day after a UN Security Council meeting that had condemned the Yemeni attacks on Israeli, or Israeli-affiliated vessels on the Red Sea and the Arab Sea. That meeting, though it brought little significant result, served as a justification for the predetermined strikes by the US and the UK to launch Operation Prosperity Guardian.

From 12 January until 9 February the American and British forces have conducted at least 15 airstrikes allegedly killing at least 34 soldiers of the forces of Sana’a and destroying a large number of Yemeni missile and drone positions. Thus these attacks would have crippled the capabilities of Sana’a to launch more strikes within its declared operation to block the Strait of Bāb al-Mandib to any shipping heading to the Israeli ports. This way Yemen claims to support Palestine during the war on Gaza putting massive economic pressure on Tel Aviv.

Indeed it is very telling that while the Palestinians themselves have launched hundreds of missile attacks since 7 October, Ḥizb Allah in Lebanon launched a war of attrition along the Palestinian border, and the Iraqi resistance groups launched around a hundred attacks on the American bases in Iraq and Syria, until 2 February the only significant reaction by Washington intervening directly came against Yemen. Which despite all claims to the contrary, would indicate that Sana’a managed to hit a nerve.

The matter is very curious indeed. On the one hand, why has Sana’a chosen to launch this attack in the middle of a fragile peace process with the Saudis, knowing full well that the reaction would come and would be devastating? On the other hand, why have Washington and London chosen to intervene directly, clearly supporting Tel Aviv in this sensitive time, when there seems to be no winning strategy? But apart from the positions of both sides, it is very significant that even though Riyadh and Abū Zabī waged a long war against the government in Sana’a and for long had asked for direct support from Washington, not at this opportune moment they chose to distance themselves. Apart from Bahrain, no Arab state took part in the operations against Yemen, at least not openly.

What are the possible reasons for this new, distant front of the war around Gaza and what could be the winning strategies for both sides? Where could this war lead and how significant this front zone is for the already very complex conflict that is rapidly escalating around Gaza?

Washington steps in

It should be pointed out that the leadership in Sanaa made no secret about its plans to support the Palestinian cause directly and militarily. On 26 October 2023, the Yemeni forces bombarded an Israeli position in Eritrea severely crippling it and killing some of the Israeli staff, but this was only the first step. Soon enough Sana’a launched a series of strikes against the Israeli positions directly, mostly concentrating on the port of Eilat, the central hub of Israeli commerce to Asia. While some of the missiles and drones reached their targets causing very limited damage, these attempts were mostly thwarted by the American navy vessels on the Red Sea and the Egyptian air defense, much less than the Israeli air defense. Tel Aviv promised to hit back, but that has so far not materialized, mostly likely due to the heavy pressure of the Israeli war machine in Gaza.

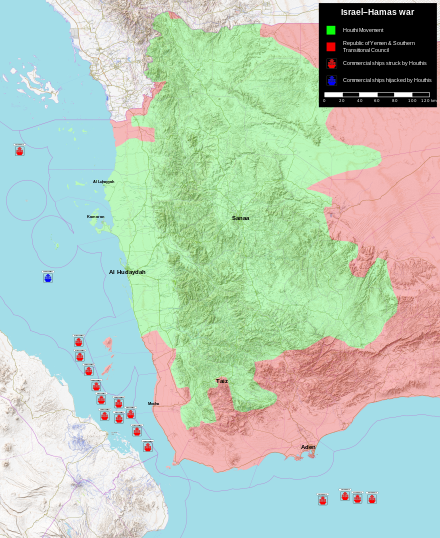

And so Sana’a changed tactics. It announced that its forces would stop any Israeli vessel, or even any international vessel regardless of its origin heading to the Israeli ports. However, these threats were largely ignored until the first major incident, when on 19 November the Israeli-owned Galaxy Leader was boarded by Yemeni troops and eventually turned to the port of al-Ḥudayda. Later on, a further 16 ships were attacked or boarded until 30 December, when container vessel Maersk Hangzhou was attacked and eventually the American navy repelled the attackers. This was the first official direct engagement between the American and the Yemeni forces and the first clash of Operation Property Guardian launched by Washington to protect the shipping lanes.

Though both Washington and London claim that the airstrikes against Sana’a are independent of the war in Gaza and only serve to provide security for marine trade on the Red Sea, the very obvious aim is to break this naval blockade against the Israeli trade, which had had a crippling effect even before the airstrikes. According to the official reports commerce in the port of Eilat has dropped by 85% by the end of December already. And regardless of the true intentions, the perception of the whole region is that the airstrikes serve Tel Aviv. That is the regional states are very hesitant even to condemn Sana’a’s attacks, let alone to join the military operations against it.

Since the first wave of airstrikes on 12 January until 9 February the American and British planes have launched another 15 attacks all together hitting around 60 targets. Though the Royal Air Force has contributed to these strikes with a smaller amount of planes and states, like France, Germany, and even Greece have sent military vessels to the region cooperating in these operations, the bulk of the force is given by Americans. Though early on it was constantly hinted that this all would serve only as a prelude until an even bigger operation is launched, so far there is no sign of that and the official narrative is restricted to retaliation for Yemeni attacks and crippling Yemeni missile launching capabilities, only to protect maritime trade. Yet, so far these attacks have not prevented Sana’a from trying with newer attacks against military vessels, Israeli, American, and British trade ships, and even direct attacks against Israeli targets. So far these attacks had very little effect and were mostly repelled. Still, the same was the case with the Iraqi attacks on the American bases in Syria and Iraq as well, until it was acknowledged that American soldiers fell and dozens more were injured. So it might just be a matter of time until the Yemenis hit something big.

Until now the American-British attacks have repeated themselves every second day, or so and allegedly concentrated on missile and drone launching positions and depots, but reports suggest that many of the targets are the same that the Saudis and the Emirates have bombarded time and against since 2015. Which never deterred Sana’a from launching new strikes, some with crippling effects. Even more curious is that reports talk about several strikes against the ad-Daylamī air base close to Sana’a airport, which has not been in service since 2015 when the Saudis bombarded it. And if the reports are true that the Iranian military is actively supporting Sana’a both with advisors and with some of its navy vessels providing intelligence, very similar to the pattern we see in Iraq and Syria it is clear that these strikes will have very little effect. In short, Washington will not be able to frighten Sana’a, nor will it be able to cripple the Yemeni Armed Forces.

Even worse, because of the escalation, even other states, like Pakistan and India sent navy vessels to the region to defend their cargo ships, though not supporting the American operations, which increased the chance of a devastating mistake. In consequence, international shipping is not secured by all this commotion, but to the contrary, naval trade is dropping even further. Very indicative is that Qatar Energy, one of the biggest LNG providers in the world announced in late January to avoid the Yemeni shores, even though Qatar has no economic ties with Tel Aviv and the shipping was never managed through Israeli ports.

The reason is very simple, the same trend in continued since December with most international large cargo carrier companies. Given the large number of military ships in a very limited area and the frequent operations, most insurance agencies are either not covering such lines, or increasing prices rapidly, simply making these routes uneconomical. And since insurance has become rare and expensive, most companies do not take the risk, even if they have nothing to do with the Israeli ports. That is simply because even with full compliance with both the coalition navy and the Yemeni forces, nothing can prevent a ship from eventually getting caught in the crossfire, hitting a mine, or being bombed accidentally. So it is better to avoid the scene altogether.

Given this pattern, it is very strange indeed to understand what Washington is trying to achieve. The options are limited. It can continue with similar strikes and eventually bring in more allied ships to give better naval cover, but that is unlikely to stop the attacks, which Sana’a vowed to continue. It can increase them significantly, but its success will be very doubtful, and eventually, civilian casualties will rise, giving rise to even more criticism. Which is mounting already because of the role America is playing in the Gaza war. It could in theory gear up for a land invasion trying to overthrow the government in Sana’a, but that is very unlikely for a number of reasons. First of all, it would be very costly, as the Yemeni forces have proven to be very resourceful on their home ground. The American forces in the region are stretched thin already, and unless there would be willing regional allies to join, this is an unbearable burden. Especially in an election year. Such allies are very hard to find now, as the Saudis and the Emirates have waged a very unsuccessful war in recent years and have already committed to a peace settlement. But even if such a huge undertaking was launched and with a massive operation the Americans could reach Sana’a, there was no alternative to the al-Ḥūtī government. Which would mean a long and atrocious conflict, very similar to what Afghanistan was.

Beyond the hubris, the desperation to do “at least something”, to simply show power in an election year, or to provide a token support to Tel Aviv there seem to be no good answers to what Washington and London are trying to achieve with these bombardments. Unless it is not about Yemen, but should be understood on a regional scale.

The complex regional equation

The rapidly deteriorating events since October 2023 made many states in the region face a very difficult dilemma. Those who supported the normalization process with Tel Aviv could not bear the moral implications and had to retract, at least to a certain level. Those who had plans to join this process had to abandon such plans, like Saudi Arabia, if only temporarily. But those which were already at odds with Washington, like Iran and its allies have faced an even bigger dilemma.

Political support for the Palestinians was obvious, but more had to be done to prove that this block was effective and could provide an alternative. It had to prove that it can reach achievements, and thus the normalization is avoidable, and effective resistance is possible. However, with American bases all over the region, it is practically impossible to start an open war even if only strictly against Israeli targets, without risking a crippling war with the US. Even a covert, but intensive engagement is difficult, as it would alienate the very states Tehran just managed to settle its relations within the last year or so and these relations are still improving. Thus, a new strategy was devised, a low-intensity war of attrition.

The most capable non-state allies of Iran in the region, with undoubted full support, launched a series of strikes against both the Israeli and the American positions. The Ḥizb Allah in Lebanon keeps the Israeli forces busy, though refraining from a full-blown war. The Iraqi Popular Mobilization has launched increasingly successful attacks in both Iraq and Syria against the American troops and their allies. These might not have been overly successful so far, but their successes are increasing and have already forced a reaction from Washington. The retaliation by the Americans hitting positions both in Syria and especially Iraq forced the Iraqi government to abandon its tenuous position and demand the withdrawal of the American troops from Iraq. And if the Americans were to leave Iraq their hold in Syria would become mostly unsustainable. This has been already a huge success for Tehran shifting the regional sentiment not necessarily towards itself, but very definitely against Washington and Tel Aviv.

The distant front in Yemen fits into this pattern perfectly. As long as the relations between Tehran and Riyadh were on the verge of open conflict Yemen was a very important leverage, a thorn in the side of the Saudis crippling them in a long and atrocious war while not getting engaged directly. And when negotiations started between Riyadh and Tehran, Yemen was a significant bargaining chip. Almost a year ago, when under Chinese supervision a reconciliation was reached between Saudi Arabia and Iran Tehran tacitly gave the green light to a Saudi-facilitated Yemeni peace process, though keeping a very close eye on the events.

Now that the ties have turned against the American role in the region, Yemen once again proved to be very important, as with closing the Red Sea shipping lanes a huge strike was taken on the Israeli economy. One far more significant and sophisticated than the direct missile attacks on Haifa, still not forcing Iran to be directly involved.

In this pattern, it can be understood that Washington is more and more striking the Iranian advisors and intermediaries signaling that more significant strikes are on the way. The same pattern can be seen in Lebanon, Syria, and Iraq, where for some time Washington gave massive intelligence support and diplomatic backing to Israeli assassination strikes, but since 2 February had to resort to direct involvement. If this deduction is correct, the strikes against Yemen will even intensify to kill the biggest number of Iranian advisors, and military personnel, or even to strike “accidentally” the Iranian navy in Yemeni waters. In this sense, direct effects on the maritime trade and the safety of shipping, even on the Yemeni political process are of very little significance. Because that is understood in a way that once Iran is pushed back these matters will practically solve themselves.

The precarious position of Sana’a

Whatever the intentions of Washington, London, and Tehran are, it is still curious how Sana’a viewed the situation. Why does it commit itself to a direct engagement with the Americans knowing that the Saudis might exploit the situation at any moment to either reopen the war or to achieve better conditions for a final peace agreement? After all, simply just allowing the Americans to use the Saudi airspace, or forbidding it can be used as leverage. Furthermore, such a major military operation might break the internal Yemeni ceasefire and reactivate the forces so far fighting against the al-Ḥūtī government. Which would not necessarily rely on Saudi support this time, but could achieve it from the Americans.

The latter proved itself to be a real possibility, as ‘Aydarūs az-Zubaydī, the leader of the Emirati-supported Southern Transitional Council soon after Sana’a launched its first operations against the Israeli targets started a series of negotiations with the Saudi leadership. The aim was clear, in exchange for military support and diplomatic backing for autonomy, or a bigger share at final negotiations after the Saudi-backed Presidential Council practically sidelined him az-Zubaydī volunteered for renewed operations against Sana’a. And az-Zubaydī had stated before that in case a sovereign South Yemen would be recognized – no doubt under his leadership – that would recognize Israel and normalize its relations with it.

Though very little is known about these talks, they must have been largely unsuccessful, as they started in early December and by February the Southern Transitional Council started no major operations, nor has it gained much attention from Washington. And no other major internal opponent has stepped up against Sana’a so far, no doubt because they failed to attract support either from Riyadh or Abū Zabī.

Contrary to expectations, not only the war did not renew between Sana’a and Riyadh, but way, after the British-American airstrikes had started the leader of Sana’a’s negotiating team Muḥammad ‘Abd as-Salām, stated that an understanding was reached between the two sides about most major issues of a future peace plan.

The leadership in Sana’a waged a huge gamble that could have reignited the whole internal war in Yemen. Instead, it proved to be influential on a regional scale. A power hub that cannot be ignored, as thus the final reconciliation of the Yemeni conflict can only come, by a direct agreement between Riyadh and Sana’a, without the significant involvement of all other Yemeni parties. In other words, with this engagement, the al-Ḥūtī government proved to be the strongest player in Yemen, which greatly benefitted from the popular sentiment outraged by the war in Gaza. This was the only Yemeni party that did something for the Palestinians.

The legacy of the American policies hit back

Though this current crisis around Yemen with all its economic implications, even the war on Gaza altogether may seem typical of the Middle East’s eternal conflicts, it could be viewed that eventually, like always before will subside, there are two very significant changes here. The first is how the traditional allies of Washington are turning away in ways so far unimaginable, and the second is now severely the dark legacy of the American policies of the last two decades is hitting back.

As for the first, it is very telling that Riyadh waged a war unseen by the Kingdom in its history, just to secure its absolute dominance over Yemen and put together a vassal state. For a great number of reasons this quest has failed catastrophically and after seven long years with little results it had to accept a peace process with the al-Ḥūtī government in Sana’a. During the war, Riyadh was desperately buying more weapons and supplies from Washington and pushed for direct involvement when the war effort broke down. Until Trump was in office there were high hopes for that, but after Biden took office relations broke so bad that now when Trump might take office once again next year there is little interest by the Saudis. If Operation Prosperity Guardian was launched two years ago no doubt Riyadh would have given its full support and doubled down with all its efforts to take Sana’a once again. Now, however, it not only refrained from condemning Sana’a’s operations but instead warned against the American strikes and called for stopping them.

That along with the similar behavior by the Emirates also avoiding renewing its engagement in Yemen even symbolically shows perfectly well how much former key allies lost trust in Washington. Even in very crucial matters. And if that could have happened, the steps like joining BRICS, or not taking sides against Russia are much less surprising. But more worrying for Washington about the future, unless significant steps are taken, even though the plan was to downsize the American presence in the Middle East to free up resources confronting China.

The other significant thing to be noticed here is the dark legacy of the American policies and how much they are hitting back. Since 2001, but especially since the so-called “Arab Spring” the American administrations followed the doctrine of “creative chaos” in the Middle East. Undermining all governments not deeply allied to Washington, creating a constant state of insecurity, in which these governments can be sacked at any convenient moment, and also making them fully understand this. Thus forcing them to be even more dependent on Washington’s “goodwill”. Whenever a government takes steps not favored by Washington that is toppled by supporting internal conflicts, like as happened in Iraq in 2014, or whenever that is not successful simply ignoring it, stating that this particular government is not recognized, and thus actions are freely taken disregarding it. As it happened with Syria, where the Americans set up military bases with total disregard for international law and the objections of Damascus.

The result is an atmosphere of instability and insecurity, wherein a great many places, thus far to the very liking of Washington, there are very few strong, effective, and capable state actors. But this is exactly what is hitting back now, as a large number of organizations established themselves, which are not at all friendly to Americans. These are now labeled as Iranian proxies, though not all of them are strongly likened to Tehran. Since there was no strong state presence, these organizations have flourished, creating their massive local basis, leadership, and supply chains providing security on the local level, but now uniting and turning against the American presence. If the Americans hadn’t crippled the Iraqi state, now they could negotiate with Baghdad not to join to take sides in the war in Gaza, or at least to limit the clampdown on these groups. The weak and artificially allied governments in the region are either breaking apart, or turning against them, and there are no capable strong allies to prevent this process.

It is said that the downfall of great empires truly starts when they swallow their vassals, which once served as a buffer against their opponents. And thus have to fight the wars itself, which had been fought by these vassals before. Never before the Americans fought major wars in the Middle East practically alone, not relying on a broad local coalition.

It is a very telling change of paradigm in a region the US was about to leave for at least ten years now.