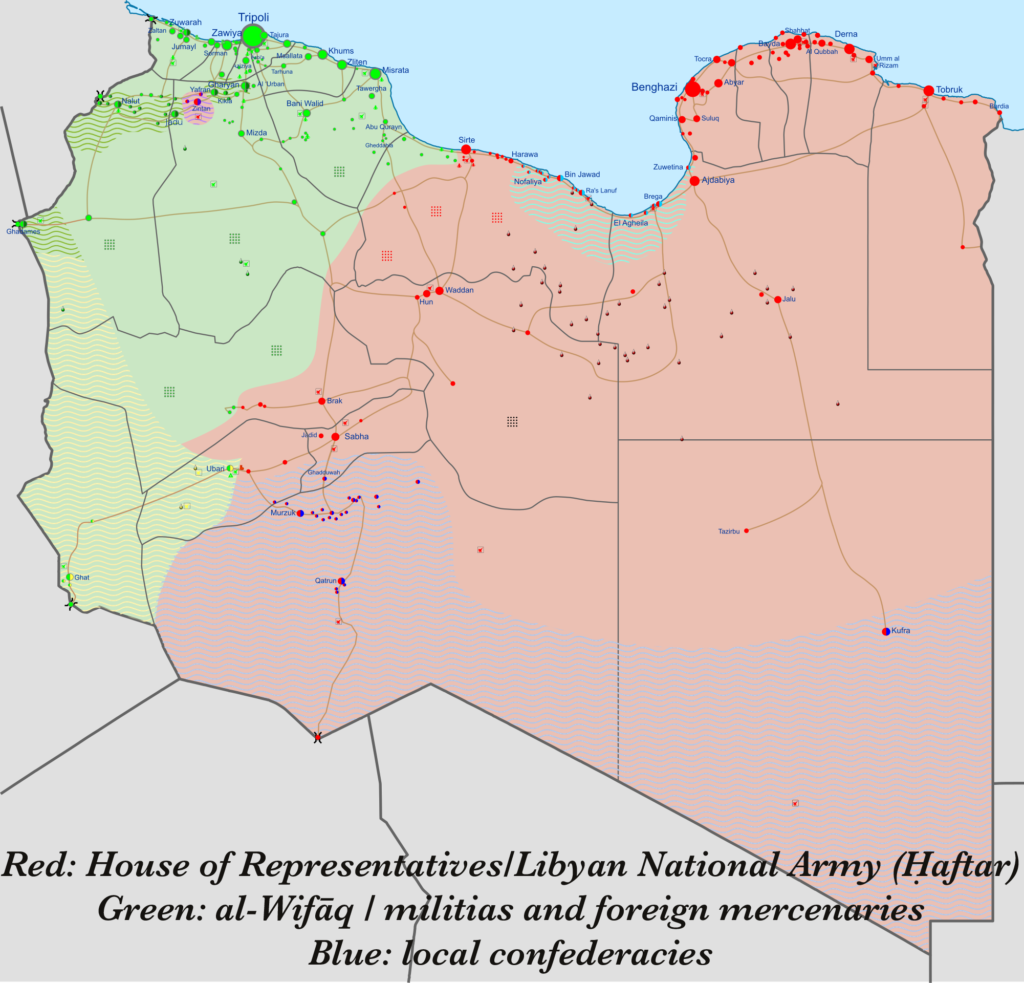

The Libyan crisis is boiling for years now, and that North African state barely witnessed any sign of stability since the downfall of the infamous Colonel al-Qaddāfī in 2011. The scenery, which was a few years ago extremely complicated with three governments and large portions of the country under informal foreign occupation and dominance of militant groups became somewhat more clear with the U.N. supported ceasefire in December 2015, which became known as the aṣ-Ṣahīrat Accords. After that, thought the local tribal confederacies still play a vital role, there have been practically two rival governments, both considering the other illegitimate, and the war went back and forth as both camps resorted to the support of local and international players supporting them.

This changing course of the war took a new turn at the end of last year, as the Tripoli-based National Unity Government (al-Wifāq) lead by Fāyiz as-Sarrāğ made a very controversial maritime agreement with Turkey, which resulted in unprecedented Turkish support, including a growing shipment of terrorist groups from Syria into Libya under Turkish guidance. Turkey even tried to persuade regional states, like Tunisia and Algeria to side its bid and to set up a permanent military base in Libya. As these attempts and the peace conference in Berlin failed, the government in the east of Libya lead by Major General Halīfa Ḥaftar launched a bitter offensive to take over the capital with substantial Egyptian-Saudi-Emirati support. That not also failed, but recently Ḥaftar suffered humiliating defeats, which started to threaten that the East-Libyan government collapses and Libya firmly becomes under Turkish influence.

So far that was “only” a widespread and fierce proxy war for influence, in which the main questions were the Turkish-Egyptian rivalry and the Turkish influence in the region, but confined into the Libyan theater. But last week all that took a very sharp turn once again. After Ḥaftar went to Cairo once again to consult with as-Sīsī the Egyptian President first announced a ceasefire and a peace initiative. Unsurprisingly that failed to attract any support, so on the 20 June, he visited the biggest army compound along the Libyan border and held a speech, which many interpreted as a prelude for open Egyptian military intervention. Since than Cairo was very active to set the ground for such a move. Not only obtaining support from the Arab League and its traditional allies in the Libyan matter, but also by France. And now other regional states, like Tunisia and Algeria show signs of bigger concern.

The Libyan crisis is on the verge of a major blow, or at least it seems like so, and many states try to brace themselves for the impact. However, the question is very valid, whether Egypt is really willing to commit itself to a prolonged engagement, or only bluffing on a major scale. Because at the same time as-Sīsī has another, and much more pressing matter to solve, where he has less tools to influence the outcome.

Within these deliberations, three other levels are very important to examine. Who is who in the Libyan crisis, and where would the theoretical legality stand? How do this crisis and the potential Egyptian(-French?) intervention affect the attitude of the other regional states, like Algeria? And where is the regional proxy war between the Turkish-Qatari and the Egyptian-Saudi-Emirati camps heading, in which a possible Egyptian intervention in Libya has the potential to be a decisive battle?

Finding legality

As the whole crisis attracts ever more outer involvement and it is clear that it is far beyond an internal Libyan conflict, as both sides receive huge support from abroad it is not a decisive, yet still an important question on whose side legality stands on. In short, none of the sides have a completely legal basis to represent Libya as a whole. But the question is still important for one major deliberation. All international forums seem to agree that the illegal foreign incursion and intervention should be stopped to enable a Libyan internal dialogue for stability and for a comprehensive ceasefire. But here the emphasis is on the word “illegal”, as both sides openly receive outer support, even on the level of military equipment. And in this context, all sides point to the Syrian and Yemeni examples, where the legal government had all the legal prerogatives to invite foreign allies to support the military cause to crush terrorist/rebel groups. In the case of Syria, though many states for long tried to placate the government in Damascus that it lost its legitimacy, it never really lost its international standing, at least in the U.N., and the existing military accords between Russia and Syria truly permitted the Russian military presence. In Yemen, though the government of Hādī was standing on very shaky grounds after Hādī resigned, escaped from Sana’a, then reasserted itself, but he was still the only elected president, so indeed he had a substantial legal basis to invite the Arab Coalition Forces, even if that was heavily contested. So in Libya, this question is bigger than a simple matter of government, as there are two competing camps both claiming to be the sole legal entity. Therefore both regard the support behind it legal, citing the Syrian example, while the one for the other camp illegal. And in this, the international community, even with the best of intentions, has to pick a side. Naturally many sides support the idea that all foreign support should stop, but as at this stage that is somewhat illusory, the work should start with the “more illegal” incursion. Otherwise, the intervention will only grow, and Egypt might just indeed move in, resulting in a very serious war. And if Turkey would choose to retaliate that would drag NATO into the crisis. Which no one wants.

The Libyan war in 2011, the international intervention toppling the legal Libyan government, and the internal war following it is a very broad topic, which has very shady details. While that is very interesting matter, not the least for a better understanding on the so-called “Arab Spring”, that goes way beyond our topic here.

The war started in early 2011, and by late August it was practically decided as the uprising forces took the capital and the former government collapsed. Several regional notions are, however, important here. The new political entity representing Libya was the National Transitional Council, which at that time was not only supported by the West and many Arab governments supporting the “Arab Spring” but also by Turkey. So much so that its first leader Muṣṭafā ‘Abd al-Ğalīl, al-Qaddāfī’s former minister of justice later moved to Turkey with his family and was a strong supporter of political Islam. But later on, even him, though practically retired from politics, supported Ḥaftar and blamed Turkey for the crisis. Meaning that from the very beginning the Turkish-Gulf involvement was very strong behind the transition in Libya. Only after this former coalition broke up in 2013 into two rival camps the struggle started to manifest. That is what we can witness in a number of frontiers from Syria to Egypt and Yemen. The other important notion that the neighboring states, even the then-revolutionary Tunisia supported al-Qaddāfī to the last possible chance. Algeria even gave shelter to the former Libyan leader’s family. That did not happen for political affiliation to the previous system, but in a fear that Libya will transform to a pool of uncertainty and militancy, which will have catastrophic affects to them. In both cases, time proved time right from border clashes to terrorist actions all originating from Libya. Therefore Algeria and Tunisia, which are both now regaining their activity want to stay out of trouble in one hand, but on the other, their best interest is not to see a new war. They are reluctant to accept Turkish hegemony on their borders and would love to oust it, but if that happens with an Egyptian intervention and open war the consequences are even worse.

After the Libyan government leading the country for four decades fell, the new leadership was characterized by mostly Islamists and former opposition members returning from abroad. Many, like the first President and the first Prime Minister holding Western citizenship. This new system managed to hold elections in mid-2012, which are the last held and internationally accepted elections but struggled to assert its control over the country and disarm the wide array of militants holding absolutely different agendas. Violence and initially sporadic militancy spiraled out of control and the political institutions started to loose weight. The most noteworthy incidents happened in October 2013, when Prime Minister at the time ‘Alī Zaydān was kidnapped in Tripoli, and in May 2015, when the last generally accepted Prime Minister ‘Abd Allah at–Tānī visiting the south narrowly escaped an assassination attempt and it took a long time for the governmental forces to rescue him from an ambush. That is the time when the most seasoned general of the Libyan army Halīfa Ḥaftar, another American double citizen, charged by the government to flush out the terrorist groups from the capital, started to act ever more independently. Based on his stronghold in the east he waged several campaigns to bring the country under control and became non-responsive to any governmental orders. The situation became unsustainable and both the Libyan government and the Libyan parliament broke up.

In May 2013 Prime Minister ‘Abd Allah at–Tānī resigned and handed power over to Aḥmad Ma‘aytīq, but the Supreme Court found the step illegal in June, reasserting ‘Abd Allah at–Tānī, who nominally stayed in office until 2016. But from that point on there were two governments with very limited power in the two edges of the country and general chaos. By U.N. endorsement from a loose confederation of minor fractions in December 2015 the Government of National Accord was formed under the leadership of a Presidential Council lead by Fāyiz as-Sarrāğ. At that point, the House of Representatives, the sole surviving body of the only elected Libyan authority after 2011 accepted the deal and there was a very real, though very fragile unity. That was the infamous aṣ-Ṣahīrat Accords, which is held by many as the new basis of legality, which should have lead to new general elections. But the rift between the two sides never really eased, fights broke out in 2016, and in March 2017 the Eastern-based House of Representatives withdrew from the aṣ-Ṣahīrat Accords. Controversially, however, both sides still maintained the validity of the accords as the basis of ceasefire negotiations in one hand, and as the basis of legality on the other.

The only positive result was the most minor factions joined ranks to one of the two camps, only the south remained mostly in the hand of local forces. Nonetheless, a level of statehood returned to the country. That was much of the result that many European states heavily pressured the Libyan sides to form some sort of functioning statehood so that it could be the basis of attempts to hold off the huge waves of migrants coming from Africa. And for that end, the al-Wifāq was heavily supported.

The last major twist in the story is that acting on international support the al-Wifāq started to look for major military supporters to break the government in the east and the forces of Ḥaftar still holding on the majority of the county. Benefiting from the fact the al-Wifāq is the local branch of the Muslim Brotherhood and that Turkey invested heavily in Libya after 2011, the link between as-Sarrāğ and Erdoğan was secured. That lead to an infamous maritime agreement at the end of 2019, which will be elaborated next week, but based on this as-Sarrāğ asked for direct military support from Turkey. Ankara accepted this and started to act. Unofficially started to pump its terrorist affiliates in Syria to Libya, which Ankara denies, but the number of these mercenaries by now reach up to some 8-15 thousand troops. Even officially Turkey supplies the al-Wifāq with military experts, training missions, weapons, sophisticated drones, money, and supplies. And Ankara holds that to be legal, as the very Libyan government recognized by the U.N. has the prerogatives to make such deal, therefore the support is legal. Indeed, however, on 28 November 2019, the Libyan Interim refused the maritime and security accord with Turkey. Even though in December it asked for it. And in January the House of Representatives also vetoed the deal, making the Turkish presence illegal.

And here comes the real puzzle of legality. Most Arab and regional states view the government in the east as legal, as that is the only democratically elected authority in Libya. This is a solid argument, however, that body is long beyond its legal term and also accepted the aṣ-Ṣahīrat Accords. So itself gave a legal basis to the al-Wifāq, regardless of the fact that it withdrew later on. The U.N. so far only recognized the al-Wifāq as the sole representative of Libya and in any form, its legality is based on the aṣ-Ṣahīrat Accords. Which gives the right of veto to the House of Representatives in major decisions and stipulates that the House of Representatives is part of this government. Now from Tripoli’s view either the aṣ-Ṣahīrat Accords is valid, in which case the veto as well, and the Turkish presence is illegal; or it became invalid, in which case it lost its legitimacy. If the accords are invalid the al-Wifāq had no right to ratify international treaties. And that puzzle is just as complicated for the U.N., which so far was the most reliable compass for legality.

Either way, both camps have some legal basis to hold on to, and both deny the very rights of the other, which at some point they admitted. In such a clear contradiction there are only two possible solutions. The first would be to wipe the boards clean, hold new interim elections, and revise the situation with the new government. That is what recently Tunisia proposed. The other is a military solution, a final showdown between the two camps. By many sides involved the first would be better, but at this stage, both governments are so dependent on their many foreign supporters that they became practical pawns in their hands. And since both Egypt and Turkey want to score a major victory against the other here, the military solution seems to be inevitable.

The shadow of war

On 20 June as-Sīsī visited the Air Force base in Sīdī Barrānī, the center of the whole Western Command to have a formal inspection.

The very cheesy and overly formal spectacle held two interesting speeches, but the main message was given at the very beginning directly from the President to the troops in a somewhat direct and informal manner:

“Be ready to perform any task within our borders! Or if the matter needs it, outside of our borders!”

That set the tone for the whole inspections, putting up a grand picture of the Egyptian military prowess. The top of the spectacle was of the course the rather long speech by as-Sīsī outlining that Sirt and Ğufra meant a “red line” for Egypt, which the “enemy dreams if it things he can cross”. Thought it was never mentioned, but the message was clearly sent to Turkey. He also outlined the minimal demands by Cairo, namely the all “foreign” forces must leave Libya with all their mercenaries, and all “militias” have to submit their arms to the Libyan National Army. At the end the representative of the tribes of Eastern Libya held a prepared speech asking the Egyptian forces to enter Libya and help it to liberate, for which as-Sīsī very ceremoniously responded that Egypt wants nothing from Libya, but as Libya’s security is part of Egypt’s own foreign invasion cannot be left unanswered.

The whole grand parade was somewhat of a reminiscence of the old days of chivalry. Continuing the effort few weeks ago, when Ḥaftar rushed to Cairo and as-Sīsī announced a new peace plan, he gave a last chance for compromise. That refuted, even responded to with rapid Turkish military buildup, now he put up a grand gesture showing all his arms to persuade his foe that a battle would not be a long one. And that is so far going on with firm diplomatic maneuvers, so it really looks convincing that this time it is not a bluff. The inspection and the speeches meant a convincing show indeed that as-Sīsī is determined, but what pushed him so far?

It should be clear that even though recently Ḥaftar lost his last major bid to take over the capital, which campaign was well supported by Egypt even supplying sophisticated Russian arms that is not the main reason here. The real reason is that Ankara became so emboldened by the recent gains that in June announced to set up two permanent military camps in Libya. One in Sirt in the middle of the country and one close to the capital. The very scale of this panned military presence clearly shows that its intentions go way beyond the stabilization of the al-Wifāq, but to secure the oil port, squeeze some $12 billion out of the Libya for permanent protection, to be a bridgehead for operations against Egypt, and be a training ground for its radical affiliates. Also, a number of other implications can be understood from that for the whole region. That is what raised the alarm not only for Egypt but rapidly brought France on board as well.

The diplomatic buildup

As mentioned before on June 6 as-Sīsī welcomed Ḥaftar and Speaker of the Libyan Parliament – in the East – ‘Aqīla Ṣāliḥ and presented a peace plan. As anticipated, Turkey and the al-Wifāq mocked the suggestion. Which at that time made it curious why such an attempt was tried at all, but by now it is clear that the decision for a major step was already taken. Cairo only took diplomatic steps to ensure backing, and to reassure that Egypt is not the invader. During the show in Sīdī Barrānī, the Egyptian leadership even fetched up Libyan tribal support asking for intervention. The same tribes, which only a few months ago were seeking Algerian favor. And it was very curious that not only Ḥaftar, or any of his representatives were not present in Sīdī Barrānī, but also all other Arab allies, like the Emirates, or the Saudis were also absent. Giving the impression that this is a strictly Egyptian decision, and by Libyan demand. But before any action, the wheels of diplomacy were put into motion. Very efficiently!

Only two days after the Sīdī Barrānī inspection on 22 June the Egyptian press could celebrate the remarks of French President Macron, saying that “Turkey plays a very dangerous game in Libya”, which France “will not tolerate”. At that gives the very convincing impression that if Egypt moves, it will have France, therefore the EU on its side, and a possible NATO involvement is prevented. Also, so far from home Turkey would might risk an engagement with Egypt, but not a direct war with France. After all, Libya’s precious as it is does not worth that much. But Cairo did not stop here.

On June 24 the Saudi-Emirati-Bahraini block announced its full support, and soon the Saudis became especially enthusiastic about the Egyptian decision, going as far to say that “Egypt’s security is an inseparable part of the kingdom’s security”. That foreshadowed what was yet to come, as as-Sīsī asked for an emergency Arab League session on foreign ministry level about Libya on 19 June. Thought originally the representative of the al-Wifāq promised not to attend, at the end it did, but that could not prevent the outcome. In a surprisingly direct resolution the Arab League renounced the Turkish intervention and practically gave a green light to Egypt. With the Libyan “popular” request and the formal Arab League mandate Egypt now has full legal authority to intervene militarily in Libya. It has the support of a powerful nation, France, and the possibility of NATO support for Turkey is eliminated. In fact, Egypt moved well, since no one dared to openly side Turkey, and Ankara stayed alone in this bid.

But is the war really that close?

A bluff?

For two main reasons it is fair to assume that this is still just a huge gamble. The first is that Egypt and as-Sīsī personally have a way bigger problem. That is an infamous Renaissance Dam in Ethiopia, which has the potential to have very serious ecological and economical consequences to Sudan and Egypt. Unlike Libya, which started way before as-Sīsī took power, this matter is attached to his name as he kept promising that Egypt will never allow this. It became a prestige matter for him, as this was one of his first quests, as he visited Ethiopia in 2015 and tried to impress his hosts. Cairo played a lengthy diplomatic game for years, but recently it seemed that it lost in all major international forums. Ethiopia’s right for the dam was supported, and even Sudan did not really side Egypt – nor Ethiopia – in this. While Libya is a troubling nuisance for Egypt, as its intelligence service and special forces can keep the Turks in the bay, and the collapse of Ḥaftar’s forces is still very far, the Ethiopian question is an existential threat for Egypt. Which was even mentioned in Sīdī Barrānī, thought rarely spoken of. The difference in tone between the two matters was huge, stressing that the Ethiopian matter is still diplomatic, but if someone wants to ready that the parade was intended for Addis that is not far fetched either.

The other main reason why war seems to be preventable is that there is not an exit strategy. What Egypt demands now would mean the full dissolution of the al-Wifāq, which is not only impossible but even contradicting the present U.N. standing. So if Egypt moves in, it either starts a limited operation until Sirt or the capital or goes on, until the al-Wifāq is finished. The former means that the al-Wifāq would only ask for more Turkish and other foreign support, and since the U.N. recognized it to be “the” government, it would be very hard legally to prevent this. The latter means that Egypt would destroy the very government the U.N. recognizes, and in the process, it not only has to face Turkish troops on the ground, and open war possibly but even would need to fetch up and safeguard a new government. But presently nor Egypt has the funds for such an engagement, nor could it take the constant loss of life in prolonging guerrila war. Even more, Cairo would have to take the pressure from the EU to stop the migration via Libya, which in part would be only increased. That is a huge dilemma.

The dilemma itself and the growing activity of the regional states all point out that there are diplomatic backchannels, mostly by Algeria, which can still give a solution. A solution in which Turkey steps back, but the al-Wifāq would still not surrender.

But as these activities are rather complex and give out a very tightly connected net, this side of the story shall be continued next week.