On 23 April – give, or take a day, or two, depending on the country – the Ramadan of 2020 has begun. As it is customary to the Arab world since the workload is smaller in this time and families are sitting in front of the TVs in even bigger numbers, this month is filled with brand new series. Series, a form of soup operas is a very popular genre in the Middle East all over, and Ramadan is always filled with brand new content. Some are focusing on Ramadan, or other religious themes, while others are more romantic, or simply just humorous entertainment to chain audiences to the screens. And as it is also customary, some are filled with subtle, or rather blatant political messages, exploiting the high numbers of viewers, and the fact the with family visits and more religious gatherings these themes are more frequently discussed. In most cases that was the tactic way to probe national opinion on certain topics, keep national consciousness high on others, or to expose the society to new ideas. There is nothing new in this, as this was the case for decades, with some series causing controversy, while others, like the famous Syrian Bāb al-Ḥāra – Gate of the neighborhood – becoming blockbusters all over the Arab world triggering a number of sequels and spin-offs.

Nothing less was expected for this year. Especially that since February it was foreseeable that the Corona pandemic will cause a certain amount of lockdowns – which indeed happened – resulting in even higher ratings. No doubt, that calculation turned out to be true. And this year was already full of major political agendas, from the Syrian war, the Iranian-Gulf confrontation, or the growing American interference. And of course, at the top of the list, the “Deal of the Century”. And exactly this field has become the major battleground now, halfway through Ramadan, as completely different series clashed over the subject, along with their supporters and fans.

Three series, in particular, one Syrian and two Saudis caused huge debates in the wider Arab public, all focusing on the age-old Palestinian cause. This year, however, all with a somewhat surprising spin.

What are these series, and what they focus on? What caused this huge interest for the matter, and what agendas they represent? And what messages they have for the future, as the year of Muslim calendar is closing to its end? Especially that regardless of their Ramadan timing, all these series seem to focus less on Muslims, and in one way, or another, on other religious groups. All in a seemingly inclusive, yet sharply different manner.

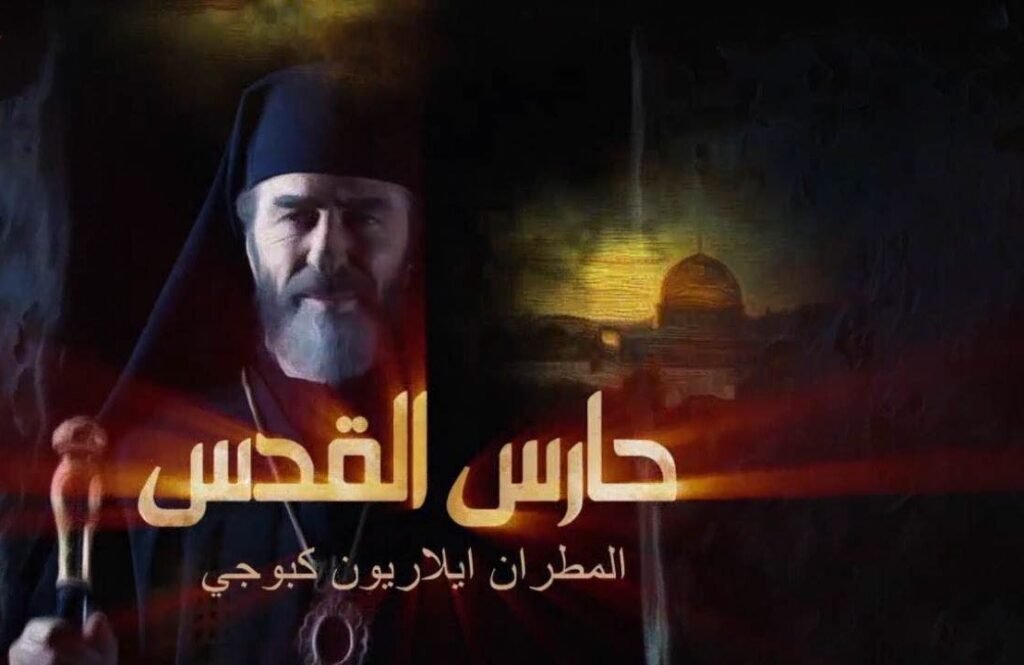

Ḥāris al-Quds – Guardian of Jerusalem

This Syrian series have a rather traditional take on the subject, yet with quite a number of fresh inclusions. The filming of this series made by the Syrian state and supported by a number of Arabic channels, like al-Mayadeen rolls around the life of Catholic Bishop Hilarion Capucci, a symboling person for both Syrians and Palestinians.

Bishop Capucci, by his birth name George, was born in 1922 in the northern Syrian city of Aleppo, in the first years of the French oppression in Syria. Which as a small child he not only lived through but famously detested. He learned to be a priest and joined a convent early on in his life, so to continue his education in Lebanon and later in Jerusalem, then still under British oppression. He lived in Jerusalem during the Second World War, which he left in 1947, as partition of Palestine was already on the horizon. As a priest, he joined the Basilian Alepian Order, a part of the Greek Melkite Catholic Church – a smaller, but Catholic branch of the former Byzantine Christianity -, where he became elected archbishop or Caesarea. Thus being responsible for the Palestinian territories and seated in Jerusalem. He only returned to his former favorite city of learning two years before the war of 1967 and the subsequent Israeli occupation of Jerusalem, which prompted a response from him. He was famously cooperative with Palestinian resistance groups, Christians, and Muslims alike, and in time became a highly vocal political activist for the Palestinian cause. Which is in fact the position most Christian churches have up to this day in the whole Levantine region. He was arrested by the Israeli authorities in 1974 for arms smuggling, for which he was sentenced for 12 years in Israeli prisons. Most of his superiors, like Patriarch Maximos V, have defended him on the ground that Capucci had a moral obligation to help oppressed people, and he was such a character that a number of prisoner exchange demand list included him, even by Muslim resistance groups. He was released by the intervention of the Vatican in 1978, after serving four years. He stayed active in later peace actions, like the Iranian hostage crisis in 1979 as a negotiator, and later was a vocal critic of the American invasion of Iraq in 2003. He was a member both in 2009 and 2010 of the relief fleets, which tried to deliver supplies to Gaza via the see. The latter was the infamous Mavi Marmara mission, on which 12 people were killed by the Israeli authorities. Once again Capucci was detained, but released soon. He died in 2017 at the age of 94 years old in the Vatican, not much after he could happily celebrate the liberation of his home city Aleppo from terrorist presence.

Ever since his death, there were suggestions of a series or a film to be made about his life, which so far was halted. Production only started later 2019, after a script was finalized, and production ended in February 2020.

The series, which is still in the mid-season, as every day during Ramadan one episode is played – and after heavy interest is expected to be translated – starts in 2016, with the joy of the liberation of Aleppo. After that, it goes on in two different, but inherently connected storylines. The first representing Capucci’s life from his childhood and his moral, ideological growth, mostly focusing on the Palestinian matter; while the other mostly about his friends and surrounding in Syria, who try to cope with the realities of the war in Syria, and the challenges of life starting again in Aleppo. Thus giving an important dual message that the struggle of Palestine and the struggle for Syrian liberation are in fact one, fighting oppression.

The style and design follow the well-known formulas of the Syrian soap genre with serious and dramatic take, with used cliches, but reinforced by the fact that it is mostly a documentary or something very close to it. Yet it has many strong messages in it, which are in fact true that Bishop Capucci was very cooperative with other Christian churches, even Muslim groups, all upholding the ideal of religious cooperation and tolerance. In on specific scene, for example, picturing the aftermath of the Israeli occupation of Jerusalem in 1967, in episode 14 Bishop Capucci orders the subordinates to bury the dead, and asks a Muslim sheikh to help. Saying he will pray for the Christians, while the sheikh would pray for the Muslims. However, when he is told that there is a number of victims who are unidentifiable cannot be known whether they are Muslims or Christians, he asks the sheikh to pray together. Also about his years in Jerusalem in the ‘40s, a character called Umm ‘Aṭā[1], a Palestinian Muslim widow resident of Jerusalem, who is constantly approached by other Palestinian to sell her house to Jewish immigrants, which she refuses despite her desperate poverty, and she is constantly helped out by Bishop Capucci, only a young priest at that time. The character is an idealized image of the Palestinian people resisting Jewish takeover, while the name and the figure gain importance later on.

The production crew has an even more inclusive touch, representing most social elements of Syria both from Muslims and Christians alike. The producer Bāsil al-Haṭīb is a Dutch born Syrian producer with known Palestinian descent, while the title role is played by Rašīd ‘Assāf, a famous Syrian television and theatrical actor, who is Christian, but from the mainly Druze inhabited southern province of as-Suwaydā’. The acting crew also contains the cream of the Damascene soaps, including Christians and Muslims alike. This is a fine addition to the already strong moral and political message as a stance by the Palestinian matter. Which for long was not only a policy of the Syrian state but the political card it exploited in inter-Arab affairs? However, beyond all political considerations, in a time when there are heated debates unseen for 40 years in the Arab world about a “Deal of Century” and an inclusive settlement with Israel, picturing such a character gave a very strong boost to the message for Syria’s standing, and for the Syrian state in its current struggle. Which showed well later, as the war of series broke out.

Umm Hārūn

The first major bomb to cause huge controversy came from the Dubai based Arabic conglomerate MBC, which has a number of satellite channels and one of the most-watched networks in the Middle East, regularly featuring Arabic and Western cinema with a tasteful selection. It was founded by Saudi investors in the Emirates in the early 2000s, given the still much more conservative and restrictive environment in Saudi Arabia at the time. In 2017, however, after a major purge in the kingdom by Crown Prince Muḥammad ibn Salmān against a big number of princes, who were seen as possible contenders for power, 60% of the shares were sold to the Saudi state. Therefore MBC, a major broadcaster, but also a massive producer of series and soaps, became under the direct influence of the Saudi court. Which of course does not mean that all material is directly overseen by Muḥammad ibn Salmān, or his staff, but indeed Riyadh has more direct access to the network, given it wants to layout messages. And obviously this year, it wanted to give many.

Umm Hārūn, title role played by renowned Kuwaiti actress Ḥayā al-Fahd, rolls around a fictional Jewish community’s life living in Kuwait. It is not explicitly mentioned, but by the surroundings and the accents, it is clearly Kuwait, though in an elusive manner that it could be almost anywhere in the Gulf. The series shows the life of this community in the ‘40s, how they live together with their Muslim neighbors before the Arab-Israeli wars with relative peace and friendship. The title role Umm Hārūn is the nexus of the plot, a talented elderly nurse in the local hospital trusted by the whole neighborhood, who regularly helps to sort out the matter in the families she encounters. Both being Muslims and Jews. The main idea is to give insight to the life of a Jewish community in the Gulf, far from what was seen before about them in Egyptian, Syrian, or Iraqi environments, and this time not at all in a negative light. It reflects their views, their inner dealings, and their responses to the major events, giving a human and natural appearance. Rabbi Dawūd, the town’s rabbi, for example, is a staunch anti-Zionist interacting naturally with his radical Muslim neighbor, the local imam, and his fellow Jews alike.

Playing Jewish characters, especially not in the usual, often parodic negative approach was something of a challenge and MBC was very open to show that it put a big effort in it. For that, they hired Bahrain MP Nansī Haḍḍūrī, a Jewish politician herself, who researched the Bahraini Jewish community’s history with great detail. She helped to give the characters a more authentic touch. So much so, that the title role – though MBC is rather ambiguous about this, often denying it – Umm Hārūn is claimed to be loosely based on a real-life person, Umm Ğann, a self-educated midwife in Bahrain, who was one of the first members of local health service. And though it is only suspected, but the whole appearance while being fictional, is much closer to the Bahraini community, than in any way Kuwait.

Quite understandably the series provoked sharp responses from viewers and public personalities alike, saying that while the series itself is debatable, it has very clear political messages that Jews and Muslim can and could live together before the Palestinian matter, there is no inherent conflict between the two sides, and their problems are like any other communities’ around the world. Suggesting that the Palestinian matter, an issue with little relevance to the Gulf people, is the only obstacle between Jewish-Israeli and the Arab-Muslim-Gulf people. Not surprisingly many attacked the show to pave the way for a settlement with Israel, and acceptance of the Deal of the Century by the Gulf, or at least by Riyadh, and that is why their signaling messages, that Jews are good people, they played helpful roles in the Gulf societies, and Palestine has little to no relevance for them. Also suspicious by many that some scenes often recall the term Israel, even before 1948, which is not only imprecise but so far was a taboo. And here the contrast between Umm Hārūn and Umm ‘Aṭā became very striking.

MBC and a number of the actors, including Ḥayā al-Fahd claimed that people judged prematurely, as the series hasn’t played much and it only pictures how Muslims, Christians, and Jews interact normally under average circumstances. In other words, it is just a message of religious tolerance. Though it did not help at all that while practically all Gulf Arabic outlets deny any real-life resemblances, in English, they admit that it was based on a real-life character. Who subtly transformed from a midwife, a symbol of backwardness and superstition even in the Arab world, to a well-educated nurse, a symbol of progress. Nor the fact that the series was highly welcomed and defended from criticism by Avichay Adraee, Arab speaking spokesman of the Israeli Army.

The biggest criticism was of course targeting the timing and the political message – also heavily denied by MBC’s spokesman Māzin Ḥayyāk – as it would be an attempt to sell the idea of Israel to the Gulf. Thought the coincidence with Ḥāris al-Quds might indeed just be a coincidence, it soon became a practical battle between the two series and the ideas they represent, provoking harsh reactions from journalists, like Algerian Salīm Bū Zaydī, to church leaders, like Greek Orthodox Bishop of Jerusalem ‘Aṭā Allah Ḥannā, all stating that such attempt will not change the general perception about Israel, only putting Riyadh into an even darker shade. And while responses were critical, even many Gulf opinions opted that the timing, the present political climate was less than ideal for such a show. Thus giving the idea that it was good, only the timing was a mistake. That, however, was soon overshadowed by yet another Saudi soap.

Mahrağ 7 – Exit 7

Mahrağ 7 rolls about the life of Ḍūhī, an average Saudi state official working in a company, who serves as the model of the ordinary Saudi man. Practically he plays the role as the general Saudi mindset, imagined in the series. Unlike the former two, Mahrağ 7 is intentionally a light comedy wrapped in a family story. The main character is being constantly exposed to different ideas by friends and family, all so far hard topics in the Gulf, and usually opens up debates about these, or just shows how these can be managed. For example, he works under a female boss, who directs efficiency Ḍūhī and his silly, rather lazy colleagues, and with whom he starts to have an affair. Later on, he is troubled by discussions with his teenage daughter, who at one point brings up the topic of homosexuality or the rights of people from other religions. In another scene in episode 3 his colleague and friend tell him that he does business with Israelis, which trouble him, but after some discussion comes the approval opinion. Since that is an average family soap it has no direct storyline, it simply follows a current, which is an ideal setting to toss different ideas into the public discussion, which no doubt was the intention. This way the kingdom, especially its heavily Western-oriented Crown Prince can finally shift opinions towards modernity in the younger generation, or – as many suspected – can give an image of such an attempt. But what are these messages?

The first idea that caused controversy was the mentioned third episode when Ḍūhī’s colleague tells him that he makes business with Israelis. And when Ḍūhī accounts him for that, the answer in plain English is: “So what?” From where he then elaborates that the Saudi state pays for wages for the Palestinian authority, instead of investing in services for average Saudis. Which is a mistake, especially that many Palestinians sold their land to the Jews, so by now they should not complain, but accept the reality. That is simply not the matter of Saudi people. That tone, though plays to simple human selfishness, is a very dangerous one, and clearly not intended to Saudi, or even Gulf audiences. Saudi and Gulf people, though sometimes complain that they unnecessarily subsidize Palestinian institutions, they are aware that this is mere friction of their expenditures and arms deals mean way bigger burden. They can hardly complain about their living standards, and those how can in Saudi never blames the Palestinians for that. Yet this is a recurring complain in Syrian, Lebanese, and Iranian discussions, where such contribution, especially politically, is much higher, and the price payed is much bigger. Also, the “Palestinians sold their land to the Jews” slogan is a recycling of an old Egyptian theme used after 1979. Which for many automatically suggested that the same project is on the way. But was this intentional, or just selfish?

The other topic causing controversy, was Ḍūhī’s debates with her daughter about wearing a hijab, coming to the conclusion that it is much rather just a custom soon to be forgotten, only change cannot happen too soon. Especially, as Ḍūhī explains that the new generation wants too much too fast. So while dropping hijab, is OK, it might lead to other unwelcome changes.

They also discuss the matter of homosexuality, for which a new, very subtle term is used, not the usually used one, which people might associate with negative feelings. His daughter argues that these people are as well humans, so they deserve human rights, they should be allowed to express their behaviors. Though Ḍūhī rejects that as they are “not human since they don’t behave as human”, the story here plays with a sensitive topic in a very appealing way. That is because homosexuality, more precisely bisexuality is very common in the Gulf. Given the strict separation of the two sexes, it is in fact not uncommon to boy communities to develop sexual relations. In usual case that exists between one person being “the woman”, while others performing intercourse on him. Some of these relations, though in a smaller group even continue after marriage. That is a relatively known phenomenon, which is a usually collective, or dual master-servant relation, besides the bonds of married life, not on the expanse of it. Which is an idea very far from the Western understanding. That was probably well known to the authors, only never clarified, making a suggestion that the two are the same. Thus granting a more appealing image to it, and making younger, more exposed generation receptive to the idea. This, however, as it is clear from the English language commentaries, is intended for the Western political public, as if Saudi was indeed becoming like the West.

MBC downplayed the criticism that these are ordinary topics, which are occurring anyways, only now brought to the open. Also that it has much smaller impact than to be to influence such major themes as the Arab-Israeli conflict. Anyways, so the spokesman argued, that is just a comedy, and there are no definite answers given. However, the matter is just not that simple. The title role was given veteran Saudi actor Nāṣir al-Qaṣabī, who is best known in the Arab world for another Ramadan series called Selfie, which was made during the crisis with Qatar in the summer of 2017. Selfie was used as a pressure method, and satire of Qatari people, as al-Qaṣabī plays a Qatari man getting involved with Dā‘iš Syrian and Iraq. That was generally very badly received by Arabic audiences, as it many times tried to portray the main character – becoming a major Dā‘iš leader on – and the average members of the terror group, as brutal and halfwitted, it is often very unclear what is meant as a joke, or satirical message, and what was presented as real. Also, it gave a very insulting image of average Syrian and Iraqi people, all being selfish and stupid, destroying their own country for money. So al-Qaṣabī’s reentry here, though he is a credited comedian, has a very negative overtone from the very beginning.

These messages put together with Umm Hārūn inevitably suggested a strong message, which is not entirely about Israel but has a major role in it. It is plain knowledge that these messages, especially in such a tightly controlled network, would never have gone through without prior approval. And the climate was well-groomed for that with a Twitter campaign even before the public got to see these series. The simple fact that the Twitter campaign was not clamped down, quite the contrary, could hardly be a coincidence.

What Palestine means

The controversies about the series haven’t even started yet when there was already heated debate about possible Gulf attempts to reach a settlement with Israel. This goes on for some time now with various statements by officials and journalists in the Gulf saying that Iran is the enemy, while Israel is not. The Gulf also conducts common security protocols via the USA with Israel, and finally here is the “Deal of the Century”. Then late April a new hashtag was launched with the title “Palestine is not my cause”, often picturing caricatures as Palestinians only want money from the Gulf, but they sell their homeland, that they caress Iranians, so they should ask money from Tehran, or turning hatred against Qataris, as they are the one who sold the Palestinian cause.

Once again, it is impossible to see that happening without approval from the highest circles, otherwise, there would have been attempts to clamp down on this current, or there would have been a public statement condemning this. But nothing. Then on 3 May, when the debate was already high about the MBC series, a Saudi journalist called Rawwāf as-Sa‘īn published a video cursing the Palestinians and Palestine. The video was rapidly picked up and publicized by the Israeli media and states that there is no Palestine, these people are a mix race, they are not Arabs at all, and that land is that of Israel alone “as it is in the Qurān”, according to his words. Some platforms quickly deleted the video, but as-Sa‘īn kept publishing even more, and that is hardly an isolated case. Already in July 2019 another Saudi journalist called Fahd aš-Šammarī not only stated the same, but even went on saying that the al-Aqṣā Mosque – the Dome of the Rock – in nothing, but a “Jewish temple”. With these kept in mind, the series is just one step forward. But why is there such a major outcry all over the Arab world, if the Gulf and especially Saudi Arabia was for a long time was known for its treacherous behavior, and its unconditional love for the West?

The uncomfortable truth is that many, thought absolutely not all, of these allegations and claims are circulating in the Arab public opinion for long. In Kuwait, for the Palestinians there took the side on Ṣaddām in 1990 during the invasion. In Egypt and Jordan for their sacrifices, which brought them only war and losses. In Lebanon for the civil war. In Syria for the role of Ḥamās and many other organizations, which were supported by Damascus, then during the war they turned and supported the terrorists, only to return once again seeking support. In fact, a great deal of the Palestinian leadership’s decisions is highly criticized all over the Arab world, even in the heyday of ‘Arafāt, and to some limit even against the Palestinians.

But that never went as far as renouncing them as Arabs or attacking the status of Jerusalem, which is considered sacred all over the Middle East, both for Muslims and Christians. There was, especially in the last two decades or so a sort of apathy that in general what has happened to the Palestinians is a sin, that they would deserve their lands, but they had a great role in what happened being careless, lazy, or even traitors. So others should not sacrifice everything for their cause. Regardless of the truth and depth of these feelings, however, there was no current so far saying Jerusalem is not sacred, the land is for the Jews by God, that the Palestinians are not Arabs or indigenous residents of that land. These are new elements, echoing the known Zionist themes.

Conflicting agendas

Beyond all religions and moral attachments, the Palestinian cause always has a tactical role for most Middle Eastern states. Even for Turkey and Iran. Capitalizing on its moral and religion importance there was a sort of race that whoever supports the cause the most deserves to lead the region or the regional Muslim community. Iran introduced Jerusalem day to the last Friday of Ramadan. Erdoğan kept cursing Netanyahu, huge boards were celebrating him as the savior of Palestine, and he allowed the famous Mavi Marmara mission. For long Saudi was one of these players on the grounds that it controls Mecca and Medina, and safeguards Jerusalem.

There were others, however, like Syria, Iraq, even Egypt for long, who saw a raising threat in Israel, which should be stopped, or al least bogged down the farthest possible. And this echoed well with Arab national ideologies, which were popular in all republican Arab states until the late ‘90s, though never really catching on in the monarchies.

Syria was and still is the place were all these factors came together and are still uphold, even with diminishing support. To keep the spirit up series like Ḥāris al-Quds are vital. Saudi and much of the Gulf never shared the enthusiasm for the “fellow Arab” Palestinians, nor they meant any strategic significance as a deterrent, but at least represented fellow Muslims to be protected. And in times, like under King Fayṣal, this responsibility was taken seriously.

It would be hard to deny that now, Riyadh and a big part of the Gulf now abandon all these positions and see nothing in Palestine, but a problem to get rid of it. With the contrast in the series, one can really see the growing rift in the Arab world about the future, in which Palestine is just one element. It goes way deeper than that, and not Riyadh is abandoning much more than just the Palestinian cause.

[1] Umm means mother in Arabic. It is customary in Arabic societies to address people by their first son. Thus the father becoming Abū, and the mother becoming Umm, put together with the name of the child. So here the character is only known as Mother of ‘Aṭā, without ever knowing her personal given name.