Less than two weeks are left for the next Iranian presidential election, scheduled to be on 18 June. This is, just like every second election, meaning every eighth year is a landmark event for the county. Though presidential elections are held every four years with no exception, it has become a sort of custom for the Islamic Republic to see every second one as important. Because of the constitution of Iran one person can only hold the office of president for two consecutive terms. Therefore usually once a person has elected his re-election for a second term is sort of a formality and given, but every second election means a new person coming to office, meaning a new administration starting. And this is why this June is very important for Tehran.

It has also become a habit in Iran to keep the most likely scenarios hidden practically until the last month, and the most promoted likely winner is obscure until the last days. That was practically the case 16 years ago when the relatively lesser-known former Tehran mayor Maḥmūd Aḥmadīnežād surprisingly managed to get into the second round, where he won against former president Rafsanğānī, a real heavyweight in Iranian politics. Though his re-election was very problematic, it came through. The same trend happened again 8 years ago, when after careful groundwork by the top state echelons a tight race emerged, and the reformist Rōḥānī became president causing surprise. This year, once again we will surely see the beginning of a new era, and once again no one can be sure about the result. That is not only true, because in Iran it is notoriously difficult to make accurate prognoses, but because this race had a very different outlook even a month ago.

By now we know the final list of the candidates. This contains none of the formerly suggested heavyweights, not even the most suggested camps. While every Iranian election has surprising names rejected to run, this time list of those disqualified is far more impressive than the actual candidates. Leaving us wonder, where Tehran is heading. So how we got here? How the race looked like two months ago, and who the picture changed? What are to most likely scenarios for and after June?

When the guessing game started

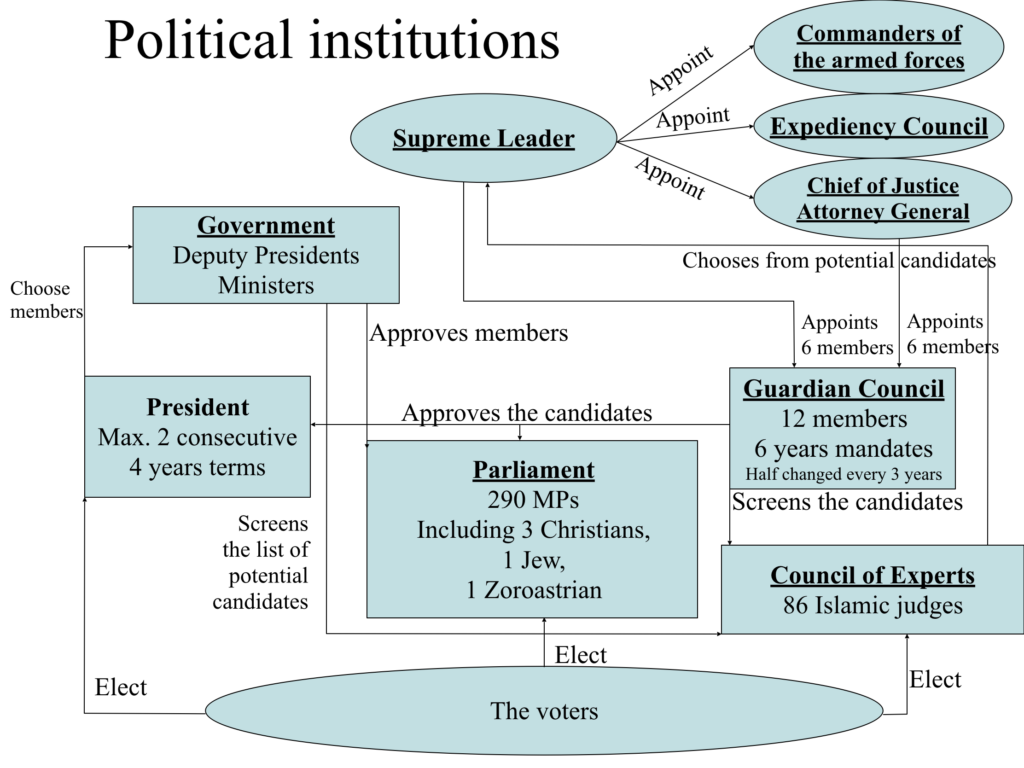

It is very difficult to guess the new president after every eighth year in Iran, and that is for several factors. First of all, many state institutions unique to the Islamic Republic have a prominent role in the careful screening and selecting process before the actual elections and campaigns.

The Guardian Council, a twelve members council of Islamic judges acting as a Constitutional Court among other things has the role to review every candidate for every directly elected office in the country. This includes MPs and the president. And since they don’t have to justify their decisions, and it is almost impossible to guess who will they let through, it is a monstrous task to predict who will truly become a presidential candidate. The Guardians Council’s decision, in theory, can be overruled by the Supreme Leader, Sayyid ‘Alī Hāmeneī, and that indeed has happened on rare occasions before, this cannot be relied on.

The other factor, which makes any prediction difficult is the secretive nature of the selection process. Not only the state institutions, but the camps and the political cliques also hide their cards until the last few weeks. There is no lengthy pre-election process, no firm indications beforehand.

The only helping factor is the so far changing nature every eight years between the more opened “reformist” side favoring internal and international compromises, and the “hardliners”. This has indicated before that this year the balance likely to shift towards the hardliners, as Rōḥānī was more from the reformist block, but was widely held unsuccessful. However, both major currents have several camps within, and there can be vicious struggles between them. Within the hardliners, this means a struggle between the army, the Revolutionary Guards (Pāsdārān), the clerical-ideological elite, and some well-connected leading figures, usually close to the Supreme Leader.

That is why usually we see a double campaign in Iran. One collecting political support for a member to be approved for elections, and later another one between the real candidates for popular support. The two often have little to do with each other, leaving many to assume falsify that just because someone has popular support, he is likely to be the winner at the end. However, like this year again, he might not even make it to the race.

This year the guesses went particularly far. So much so, that at a certain point, not even the actuals politicians were assessed, but the camps behind them. For long it was held that this year the Pāsdārān will overpower every other camp and will present several strong candidates. It was such a strongly argued case that for long the only viable alternative seemed to be the army itself.

The first heavyweight to appear was Brigadier General Ḥosseyn Dehqān, a former Air Force commander within the Pāsdārān with an impressive career. He was one of the founding members of the Pāsdārān and kept moving up in the political scale at every administration until he was finally made Minister of Defense in 2013 by Rōḥānī. Though he did not continue after 2017 and his office was taken over by the regular army, he became the personal military advisor of the Supreme Leader. These excellent political ties, in theory, meant support and trust from the reformists, the hardliners, and by Hāmeneī. He announced his candidacy in September 2020, being the first one to do so, and it seemed he is a sure favorite.

His bid was, however, only a green light, as usual, the armed forces kept some distance from the presidential post. Suddenly Pāsdārān candidates started to pour in. Most important amongst them, were Brigadier General Sa‘īd Moḥammad, and Brigadier General Rostem Qāsemī. Sa‘īd Moḥammad still 52 counts to be still very young, and he is an engineer. For years he was the commander of the Hātem-e l-Anbiyā’ Construction Headquarters, the top military contractor and developer company in Iran. A cool and precise character with little political affiliation. Rostem Qāsemī is usually mentioned as briefly being Aḥmadīnežād’s Oil Minister for few years, but much more important than he was the top financial director of the Pāsdārān’s elite Qods Forces. He is a more vocal, conservative, and hardliner politician.

This trend sparked the reaction of the hardliners’ more political branch. Many influential politicians came forward and became top candidates, who were either not members of the Pāsdārān, or left it long ago with still influential ties, but no direct involvement.

The Conservative reaction.

One of the early contenders for the post from the conservative line, who is still fairly acceptable for many more moderate circles as well was Moḥammad Bāqer Qālībāf, the current Speaker of the Iranian Parliament. He had a long and successful military career in the Pāsdārān eventually becoming one of its top commanders and head of the Aerospace Division. As such, at the time of the 1999 student protests, he was one of the hardliners calling for strong measures. That year he became the Chief of Police, but as such he was surprisingly moderate and reform-minded, which proved to be very successful.

In 2005 when President Hātamī was leaving office he ran for the presidency for the first time. For that end, he resigned from all of his military and police positions and left the army circles. Though these ties came in handy later on. He had considerable support, but eventually lost and became only fourth. After losing this race he ran for the mayorship of Tehran, which he won, and became mayor of the capital until 2017. He ran again in 2013 when he was rather considered as a symbolic contender behind the much more preferred Sa‘īd Ğalīlī, whom we will discuss later. Nonetheless, Qālībāf performed extremely well and became second after Rōḥānī. Was it not an era for the “reform party”, he might have even performed better, as he has considerable support from the Pāsdārān from his military past, the entrepreneurial circles after his mayorship, and even the reform-minded groups for having a reputation of being fairly rational.

Qālībāf left the mayorship of Tehran in 2017, and for some time he was a known politician without a serious position, slowly losing ground. In May 2020, however, he became Speaker of the Parliament. This move was viewed by many as the first possible attempt to prop him once again as the most likely conservative candidate since it was clear that after Rōḥānī a hardliner shift is on the horizon. By February 2021 some assessments put this year’s election between Qālībāf and Dehqān, meaning the political conservatives and the army hardliners.

Interestingly, Qālībāf as Speaker of the House succeeded an even bigger heavyweight, ‘Alī Lārīğānī, who also nominated himself for the presidency this year.

‘Alī Lārīğānī is not only a very big name in Iranian politics on his own right, which some impressive features, but he is also the head of his own political clique centered around his family. There are political family cliques in Iran, but rarely so openly operating and far-reaching as the Lārīğānī family. Though born in Nağaf, Iraq, he is from a very reputable religious family, as his father was Grand Ayatollah Mīrzā Hāšem Āmolī. Lārīğānī also became a Pāsdārān commander but left it for education studying computer science, politics, and religious jurisprudence. In 1994 he became the director of the Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB) the official news and telecommunications authority of Iran, after briefly being a Minister of Culture. He left this post in 2004 and ran in the 2005 presidential elections. Though he lost and became only sixth, his career skyrocketed from here. Between 2005 and 2007 he was the Secretary of the Supreme National Security Council, in 2008 he was elected MP from Qom, the religious capital of the Islamic Republic, and almost immediately was made Speaker of the House until last year. Thus he became one of the top officials of the country.

His real power, however, emanates from his family ties. He is the strongest among the five Lārīğānī brothers. The eldest one is Moḥammad-Ğavād Lārīğānī, an active politician and academic, one of the top foreign policy advisers of the Supreme Leader. The second brother is Fāẓel Lārīğānī, an American educated physicist, MP, and university dean, who is more known as a businessman of the family. He was heavily attacked under Aḥmadīnežād, as a symbol of the family ran corruption in the state, after which his influence fell back, but that did not harm his famous brother seriously. The third brother is ‘Alī Lārīğānī, the head of the clique. The fourth one is Ṣādeq Lārīğānī, the cleric and most hardline member of the family with an even more impressive career. Though coming from the religious circles he had outstanding ties with the state military and intelligence circles. His first major post was being a member of the Guardian Council for eight years, and since 1999 he is a member of the Council of Experts. This later state body is made up of Islamic scholars with the sole duty to oversee the activities of the Supreme Leader, elect a new one in case that is needed, and possibly even remove him. In this, he represents Mazandaran Province, the family’s ancestral home. Though in 2015 he himself caused controversy defending ‘Alī Hāmeneī starting that it is not permissible for the Council to supervise the Supreme Leader. In 2009 he became the Chief Justice, the leading justice position of Iran for ten years. And in late 2018 Ṣādeq Lārīğānī became Chairman of the Expediency Council, the most senior advisory body of the Supreme Leader, practically his extended arms in the state. He is known to be one of the staunchest supporters of Hāmeneī and the current state system, but he is also the one most surrounded by accusations of corruption. The last brother, Bāqer is a reputable medical researcher and doctor, the least political member of the family.

This inner circle is expanded with the ‘Alī Lārīğānī’s wife’s family, the Moṭṭaharī, with some known moderately reformist politicians; and an uncle, ‘Abd ‘Allah-Ğavād Āmolī, one of the most senior clerics and philosopher of Iran. This massive family clique has a huge influence with several allies and distinct family members, influencing newspapers and parts of the media. They have extended business interests and excellent ties both in the Pāsdārān and the clergy, mostly on the conservative side, but with some liberal elements. ‘Alī Lārīğānī himself, who is considered to have reached the right age and experience to lead the country is a very rational, practical man, not and an ideology centered figure, who is slowly distancing himself from the hardliners and thus viewed in a more positive light.

With the rise of the military as the most potential power to give the next president, Lārīğānī also entered the race in May. And it should be mentioned that Lārīğānī has excellent ties with Qālībāf, meaning that they could have potentially help each other, or step back for the other’s sake.

The conservative circles, or at least as it is viewed in the West had of course yet another big name in the race, though within Iran he is by now a phenomenon on his own. He is former president Maḥmūd Aḥmadīnežād, who had tried to return before, in 2017, but that year he was not disqualified from candidacy. While president he tried to build up a separate political current away from the “traditional” camps, even being critical of the Supreme Leader, but by the end of his tenure, mostly due to internal scrutiny and misjudged foreign policy steps he was an ostracized man. He still has some following and does not count as a total outcast, but he is held dangerous to the whole establishment.

The reformers’ dilemmas.

The reformer wing was more in trouble to offer a suitable candidate, who can carry on the Rōḥānī administration, having a bad reputation for the failed attempts in the last years, but still having sufficient support from the top state leadership. Rōḥānī came to office in 2013 with great promises and there was a visible strategy behind him. After putting together a proficient team from the pre-Aḥmadīnežād era’s best officials he wanted to achieve a viable nuclear deal and lead the country out of the sanctions. As a result, the economy would have been boosted, and the revenues would be channeled to welfare programs to raise the living standards. In this process, the extreme confusion of the bonyāds, the religious endowments, which constitute one of her major pillars of the welfare and social security system could have been finally put into order. Built on this success sufficient inner stability would have been achieved for the most important task, electing a new Supreme Leader. ‘Alī Hāmeneī could have handed over his duties to a younger leader. A huge program, to which Rōḥānī was an ideal candidate, though after Aḥmadīnežād he was very much under control.

The initial first years were of major success and though there was fierce opposition, the nuclear deal (JCPAO) went through. The problems started under Trump, as the JCPOA broke down, which gave a huge boost to the hardliners. Nonetheless, Rōḥānī tried to clean up the bonyāds, but in vain and the economy almost collapsed. Largely because of Trump the situation became so tense in the region that the current administration was slowly losing control to the Pāsdārān. That is why the likelihood of a military presidency was so plausible. That is why it was difficult to find someone following Rōḥānī, though this current still has considerable support.

Two names were mentioned constantly. The most likely was Rōḥānī’s Foreign Minister Moḥammad Ğavād Ẓarīf, an iconic personality, who was often seen even more capable and in charge than his president. He was suggested to run the current administration from 2021 as president, but in many interviews, he categorically denied such suggestions. Nonetheless, he was considered as a possible last-minute surprise for long, as he was one of the few to stand up to the army and criticize it openly in case they meddled in state affairs. In 2019 for example, he briefly resigned after Syrian President Baššār al-Asad suddenly visited Tehran, because the meeting was arranged by the Pāsdārān and the government was largely kept in the dark.

All hopes about Ẓarīf, however, were cut short after a scandal in late April, when an interview was leaked to the public. In this three hours-long interview with an Iranian economic journalist, Ẓarīf heavily criticized the Pāsdārān and its interference in state affairs. After the scandal Hāmeneī himself, though not directly mentioning Ẓarīf criticized his for the interview. Ẓarīf had to apologize publicly and revoke his statements. That meant that his political career is over, at least for now. The whole matter was extremely strange and controversial. Why would such an experienced diplomat state such things in tape? Why was that made public and why was there no “official” version of it, if the interview was intentional? Though it was viewed by many as a plot by the Pāsdārān to discredit him, it is still a very obscure event.

With the certain fall of Ẓarīf, though officially he never even wanted to nominate himself, the next best solution for the current administration was First Deputy President Esḥāq Ğahāngīrī. He was once a close protégée of late President Rafsanğānī as Minister of Mines, and later Industry. He is a professional, and much less apolitical, but became a loyal and reliable administrator under Rōḥānī. He even ran in the 2017 presidential elections and was approved by the Guardian Council, but stepped back in the last minute for Rōḥānī, who won his second term that year. In theory, he could change place with Rōḥānī, and thus the same government would continue. But on his own, he has very limited support.

Apart from them, not many openly reformist politicians dared to step up. There is very limited space between still being an alternative to the current administration and criticizing it, but having sufficiently strong appeal to be distinguished from the hardliners. Some old reformist could have been put forward, like Mahdī Karrūbī, or former Prime Minister Mūsāvī, who were both former presidential candidates. They were arrested, however, in 2009 and are still under house arrest. Thought in 2013 Rōḥānī suggested many times that soon they shall be released, that hasn’t happened since. Which is one of the biggest disappointments politically for this government. As we can see in the result, there were only very lightweights left on the reformer side.

All odds are off

And finally on 25 May came the result from the Guardian Council announcing the all together seven names, who were approved. It was shocking, even by Iranian standards. No candidates of the army or the Pāsdārān were approved, not even Dehqān. Though the ban on Aḥmadīnežād was not a surprise – given most of his top aids are still under arrest -, it was more surprising to see that even Qālībāf and Lārīğānī were banned. We should realize that Aḥmadīnežād was once president, the other two were approved candidates before, so their rejection questions the whole process.

The reform side could not celebrate either, as Ğahāngīrī and all other possible reformists were also disqualified. Rōḥānī a day later in a rare move by him opened a public debate, by writing a public letter to the Supreme Leader urging him to rule over the Guardian Council’s decision and allow “more competition”. This was rejected almost immediately, meaning the list is final.

Much of this shocking result could have foreseen, as for the first time the Guardian Council even before the nomination presented qualification requirements to be met. This has already caused uproar and fierce accusations. Though in a funny twist, Lārīğānī was rejected for not meeting the experience requirements, regardless of his former posts.

All the expected big names fell out. From all sides. There is no army nominee either. But who is left?

The final list

The list of the final seven candidates is very uninteresting. There are no real big names. The most likely main candidate, to whom the field is flattened is Ebrāhīm Ra’īsī who is already treated by the state media as the next president. Ra’īsī is a cleric, like Rōḥānī. He was Tehran’s Prosecutor General and in 2019 he became Chief of Justice, succeeding Ṣādeq Lārīğānī. He is not a particularly strong personality, but a fervent supporter of Supreme Leader Hāmeneī. He ran for president in 2017 for the first time but lost.

The other two conservative candidates are Sa‘īd Ğalīlī and Moḥsen Rezāī. Ğalīlī was once Secretary-General of the Supreme National Security Council and chief nuclear negotiator. Ğalīlī was one of the top conservative candidates in 2013, but he is considered extremely hypocritical and a weak supporter of the Supreme Leader. His loss in 2013 coming only fourth was a major disappointment for his supporters. Rezāī was one of the founding members of the Pāsdārān and skillful technocrat. He ran for the presidency several times and was never rejected, which is an impressive feat. But he is the most unlikely to win. Though he is not without merits, he is usually a useful extra in tight elections.

There are three lightweight reformists as well, out of whom only Moḥsen Mehr ‘Alīzāde has some reputation. The only considerable alternative to Ra’īsī is ‘Abd an-Nāṣer Hemmatī Director of the Central Bank. However, he is no match for the establishment nominee, as has little support, and reportedly even Rōḥānī’s camp is not behind him.

Is it more paved this time?

With the shocking amount of rejected big names and with no real big favorites in the race left it is fitting to assume that Ra’īsī is being groomed for president. That is how he is viewed not only by all Western assessments at this point but even within Iran.

In this case, only the election turnout is the question, which was always a priority for the establishment to prove the legitimacy of the system. Yet this time it does not seem promising.

And here comes the question. Why Ra’īsī? He is lacking a strong character, but Rōḥānī was the same. He is extremely loyal to Hāmeneī, which will be extremely needed if in the next eight years the Supreme Leader has to be replaced. He is a member of the clergy and surely not someone with a specifically dark record. There seem to be similarities between him and Rōḥānī, though Ra’īsī is more from the hardline wing. With him the overtake of the army can be prevented, the conservatives are satisfied, the Supreme Leader keeps a firm grip on the state, but he is still not a specifically harsh person.

So he might just be an acceptable compromise. At least for the state leadership. However, no Iranian election is ever predetermined. The system manipulates the game until the final list is done, and this happened as well this year. But the actual elections are mostly free, so the citizens do have the final word to say, even if their choices are limited. That had caused big surprises before. In 2005 all was set for Rafsanğānī, but the people rather chose the then-obscure Aḥmadīnežād as a protest. In 2013 most guesses went for Ğalīlī, who didn’t even make it as the second. So it is not decided yet that Ra’īsī would become president, no matter how much he is obviously groomed.

The real question is, however, as the negotiations about reviving the JCPOA are going forward in Vienna and there is a more understanding American administration, how much of Rōḥānī’s staff and policies will stay. How big of a change is coming.