Once the Romans called Yemen Arabia Felix. Depending on the interpretation that could either mean Fertile Arabia, or Happy Arabia, thought the latter became universally used. And what a sarcasm this is for land, to where even mighty Augustus only dared to order one campaign, and after its devastating failure never returned! And such was the faith of every empire, which was foolish enough to ever set foot on it. Even after a decade that the mighty Ottoman Empire on the zenith of its power arrived here it already gained the name, the graveyard of Anatolia. And the same scenario kept repeating itself even to our age, even with the British and Egyptian President Ğamāl ‘Abd an-Nāṣīr, all failing here, making Yemen just a graveyard of empires as Afghanistan.

Yemen was for long on our agenda. Not only for the war go on there for year, which is not any less perplexing than the equation in Syria, or Libya, but because very little is known about this land and its people. And the last few weeks were full of news, which makes it very proper to finally look into this rich land. News, which are not only almost completely absent from the main headlines, but also covered up with great effort, because they are for the biggest embarrassment of one of the best friend of the West in the region, Saudi Arabia. Some considerations, however, are much more troubling for the West for its own right, than for the Saudi war machine. Which is failing big time.

Not like the news on Syria, our topic for the last three weeks, are showing calm. Quite the opposite, the equations there are getting ever more complex by every passing day. But as the fronts are on the move and the political considerations are even bigger, we still need some time to wait for some partial result, so we could evaluate a result.

The bountiful land of Yemen was once the cradle of the Arabian-Sabaean civilization, with its own writing, culture and even religious heritage. It is the home of such eternal human heritage as the Queen of Sheba, the South Arabian kingdom of Saba and the Damm of Ma’rib, all relatively lesser known by now. No one could conquer it, or stay here for long, only by imposing local allies and client states run by Yemenis themselves. This is the lesson America never learned, but even the Saudis failed to keep in mind, when in 2015 they launched their “international” intervention. Reaching to its fifth year by now it not only brought no gain to Riyadh, but by now most former allies left and the kingdom starts to feel the pain of it.

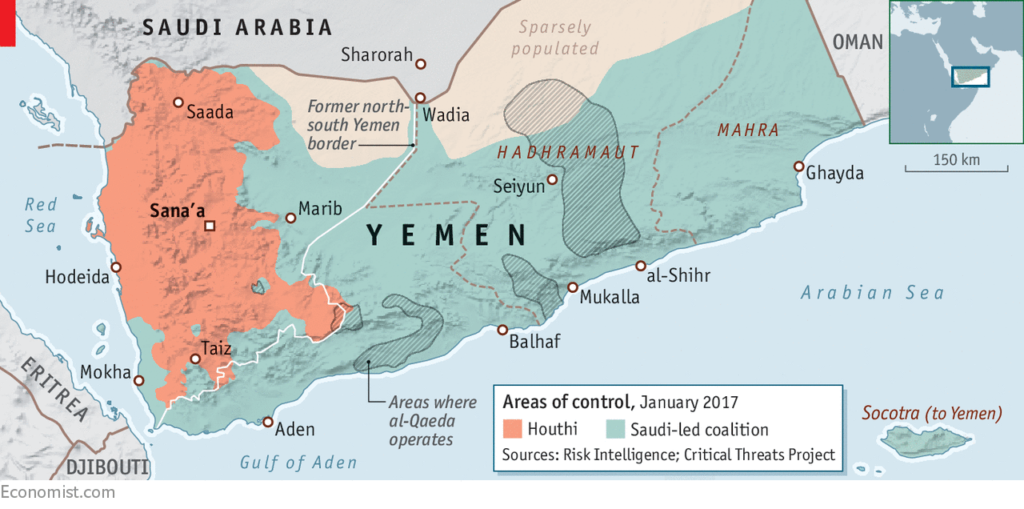

On 15 February the Yemeni forces for the first time shot down a sophisticated Saudi Tornado fighter, which was made even worse by revelations that the pilots were apprehended, and they are not Saudis. This was followed by surprising retaliation by the Yemeni forces against the kingdom, hitting as far as Yanbu‘, which caused massive panic. Not only for Yanbu‘ being a massive industrial hub, but because this hit came only half a year after the infamous Aramco hits, after which both Washington and Riyadh vowed that this was a one-time event. With the recent offensive of the Yemenis in al-Ğawf, the meltdown of the formerly Saudi-Emirati backed Yemeni government and the withdrawal of the Emirati forces the table is now turning. This was further underlined by the recent announcement of the Yemeni forces unveiling new air defense systems, which for the first time even the Saudis admit as being locally manufactured ones.

What heritage Yemen has? What lies behind the current crisis and how the Yemenis are now turning the table? Where is the place of the West in this, and why the events of Yemen are almost completely absent from the news? And how all these might change the course of the Saudi family even? These matters will be our topic for the next two weeks. Starting this week with a rough picture about how things got this far.

Happy Arabia, Fertile Arabia

People usually associate the word Arabia with a barren desert landscape, a poor, isolated and backwards region, only recently becoming rich by oil. This, however, is just faintly true to Yemen, the home of the once formidable South Arabian civilization. This is a much more fertile place than the inner parts of the Arabian Peninsula as the large mountain ranges receive more rain, but it also make it almost impregnable for any invaders.

Some eleven centuries before Christ the big cities in the inner regions and along the coastline flourished with such cities as Ma’rib, Ṣirwāḥ or Sana’a of the Sabaean kingdom with local states forming up, which created a civilization with its own pantheon of gods and writing system, having an impact on the the Peninsula, but even on Ethiopia or Somalia. Around 940 BC in Ma’rib the famous dam was built, a marvel of architecture, which was the foundation of progress. Much more than that, however, that is probably the time, when the first multilevel mud brick houses were built so characteristic of Yemen, which are true engineering marvel until now. More so that these were not palaces made for kings, but ordinary dwellings for local people.

The soon progressing Sabaean kingdom conquered most of what is now known as Yemen, regardless of the birth of a local state around the current city of ‘Adan and was made rich by trade. Trade both of transfer crossing the Bāb an-Mandib in the southern tip of the Red Sea, and locally produced spices and incense. Though several centuries later, but Yemen was the home and center of coffee production, which it ruled for centuries. Sabaean rule begun to decline with the resurgence of local states, but was on the rise once again at the time of the Roman invasion attempt under the rule of Augustus. Though the invasion was repelled successfully the Sabaean state started to fall apart and the new rising power was the kingdom of Ḥimyar around the same area, what is now Sana’a. The fight for power between the two main powers and some local small state went of for almost two centuries back and forth until the final victory of Ḥimyar around 270-280 AD, which lasted almost until the birth of Islam.

Later Roman and Byzantine attempts were made to convert the kingdom to Christianity, a state already monotheistic in its nature, but that was resisted and some local warlords were basing their rule of Jewish religious convictions. Thought the extent of the Jewish religious influence is highly contested, there were major clashes between the different factions and Ḥimyar was eventually closing on to Christianity. Around 525 AD a joint Ethiopian-Byzantine campaign was launched, only to impose a local client ruler, which lasted briefly. Byzantine Emperor Justinian I tried to persuade local rulers to a campaign against Sassanian Persia. That was part of the Roman and Byzantine efforts to force fruitful alliances and cultural influence over this important transit region, rather than direct control. This was successful in Ethiopia and along the African side of the Red Sea, but much less in Yemen. Infightings lead to the collapse of the kingdom and the breach of the great Ma’rib dam around 560-570 AD, which is marked in the Islamic-Arabic traditions as the starting point of the main Arab tribes to the north. But it was surely a turning point and the beginning of the collapse of the South Arabian culture, as around 570 the Sassanian Persian Empire captured ‘Adan and Sana’a, imposing an indirect rule outside of the cities. A model later copied by all later invaders.

Yemeni tribes soon flocked under the banner of Islam even in the lifetime of the Prophet and their campaign to expel the Persians was largely successful, even before Muslim conquered Iran. In the early Muslim era Yemeni tribes highly contributed to the Islamic conquests, gaining a reputation of fierce warriors, which lasts until now. Regardless of that, around Nağran major Christian and Jewish communities stayed existent until the 20th century. Several Yemeni tribes emigrated to other parts of the Muslim word setting up local dynasties from Syria to Andalusia, but Yemen stayed a stabile and reliable part of the Muslim Empire. At least until the last decade of the Umayya dynasty (660-750), when a major ‘Ibādī revolt started here and in Oman (Magyar). While that was mostly successful in Oman and it served as the foundation of a departing Omani progress, in Yemen that largely failed and central rule was reinforced.

This central power, however fell apart around 818, when a local dynasty around the coastline imposed largely independent rule in Tihāna, nominally under Abbasid rule, but the plains saw the resurgence of the Ḥimyari clans and the eastern parts of current Yemen stayed under ‘Ibādī influence. In 897 the first Zaydī Imamate was created along the eastern coastline, which was a Shiī movement led by Yaḥyā ibn al-Ḥusayn. The movement often called fiver Shiīs, or semi-Shiīs, much resembling the ‘Ibādīs. Yaḥyā ibn al-Ḥusayn managed to convince much of the Yemeni tribes to his doctrines, but his quest to unite the southern tip of the Peninsula largely failed and Yemen was a scene of major wars between powerful regional mini-states. Thought this first Zaydī state was largely unsuccessful, the cultural impact was significant in two ways. In time much of Yemen rejoined the Sunni world, nonetheless many local customs and beliefs are distinct and deep-rooted in these Shiī traditions, while on the other hand Shīi sentiments stayed strong all over Yemen.

That is probably the reason why the end of the turmoil was reached with the ascendence of a new Shiī state, the Ṣulayḥī dynasty around 1040 in the highlands, which soon not only united much of Yemen, but around 1060 even conquered Mecca. That state grew strong once again by reestablished trade and agriculture. It is also interesting to mark that this period witnessed some strong female rulers all positively remembered in Yemen, and at that time Yemen was a source of Shiī missionary work to the East. The Ṣulayḥī state started to fall apart some hundred years after its formation, once again by the rise of local rulers in the big city regions, and the end came from Egypt. In 1171 the Ayyubid state of Saladin (Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn Yūsaf ibn Ayyūb) took over the then Shiī Egypt, imposing Sunni rule once again, and soon ventured to capture Mecca and Yemen. That mostly happened along the coastline and even in ‘Adan and Sana’a, but resistance mostly on Shiī terms was strong among the tribes and by the 1220s Ayyubid control was lost over Yemen.

Under the next two dynasties of the Rasūlī (1229-1454) and the Ṭāhirī (1454-1517) states central authority was rebuilt around the major cities, while the Zaydī resistance was either ongoing, or bought off in the highlands. That is the time, when Yemen was growing rich once again upon centralized state authority and economic progress. In which coffee played a pivotal role. It was also the time of reimposed Sunni rule and learning, regardless of the strong presence of the Zaydī imams, and far from the major frontiers of the Middle East Yemen was fertile and thriving land. The Ṭāhirī state was noticeably weaker and less effective, and at its end saw the arrival of newer outer powers trying to impose their control. First the Portuguese taking Socotra and unsuccessfully trying to built bridgeheads in the mainland, and then the Mamluk Empire of Egypt officially to help against the invaders, but soon to try to take it over. Their hard fought victories, however, were came to be vain, when Egypt was conquered by the Ottoman Empire in 1517. Which soon brought the Turks to Yemen.

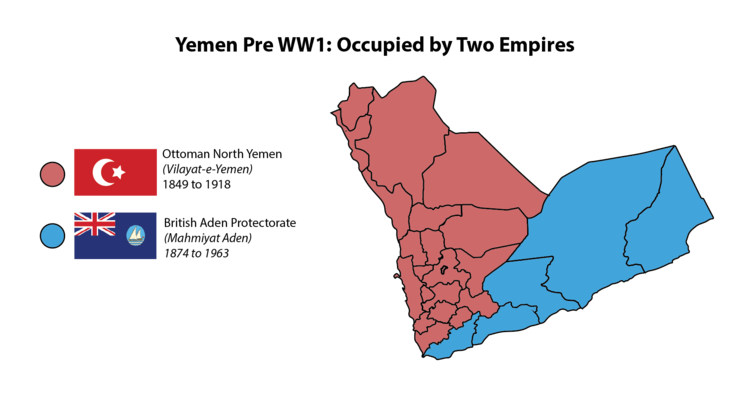

The Ottoman Empire sought to conquer Yemen to safeguard the holy cities and to benefit from the trade routes, but hardly ever succeeded controlling more than the eastern coastline of Tihāna. And when their control went farther it was due to alliances made with local Yemeni tribes, though originally the Turks saw Yemen as an easily target for its lack of central authority. Nonetheless Turkish armies kept melting away there and Yemen still marks the largest amount of governors killed in office. Even formal authority, thought conditions were often chaotic, only existed with imposed clients in the coastal cities and fragile truce with the Zaydī imams in the northern plain. All major expeditions on the grounds that Zaydī Yemenis were Shiī infidels – a recurring theme in our present age – were met with eventual defeat, and shaky truce deals. Overall the Turkish control was very fragile and the tribes and the Zaydī imams were in control, mostly even in Sana’a.

In 1839 the British occupied ‘Adan from its local rulers after trying to impose a client statehood, but this direct rule could not last even for the mighty British, as resistance grew strong and all economic gains from ‘Adan were ruined by constant fights. In 1850 ‘Adan was made a free zone under British supervision with massive numbers of foreigners pouring in, but this relative calm rested upon the relations with the tribes of the adjacent regions, all taking subsidies from the British. The British presence alarmed the Turks and there were even Yemeni wishes to reassert some central authority. The new Ottoman invasion started in 1872 and was costly. It could retake most of Yemen, not disturbing ‘Adan – a border agreement was reached between the two in 1905 -, but resistance depleted the Turkish troops and finances. Even the partial successes were due to massive attempts to incorporate local lords to the provincial authority, but that lead an ever less effective state management. Thought in 1873 Sana’a became the seat of the new Turkish province of Yemen, governors soon suggested to evacuate the highlands and resort to controlling the coastline. After several rebellions devastating for the Turks a deal was cut between the Empire and Zaydī imam Yaḥyā Ḥamīd ad-Dīn al-Mutawakkil, recognizing him as autonomous ruler of the inner lands. Turkish control nominally continued until the end 1918, when they left.

The birth of the modern Yemen

With the Turks gone imam Yaḥyā restarted his quest to oust all foreign powers and to take all Yemen, not recognizing any former treaty with the British. They resorted on the modern weapons and the local supporters fearing the rule of imam Yaḥyā. All that brought little fruit and fear of losing this possession only grew as in 1926 Italy formally recognized the al-Mutawakkil kingdom in the north. Which though fighting a seemingly pointless war on multiple fronts was a formidable power, as it was the center of resistance even for the people of al-Ḥiğāz – the area of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina – seem support from imam Yaḥyā against the recently imposed Saudi Wahhabi control. The al-Mutawakkil kingdom was therefore fighting a multifold war against the Saudis, the British and the latter’s local allies, mostly gaining the upper hand, British control only exiting in the ports, like ‘Adan and al-Ḥudayda. Eventually imam Yaḥyā sought a compromise, and in 1934 signed accords with both of his enemies. With the Saudis that meant relinquishing his claims for the territories of an-Nağrān, ‘Aṣīr and Ğāzān for 20 years. Thought that border eventually became final with the passing years, that point is important for two distinct points. First of all to understand that in these “Saudi” provinces a significant portion of the local population identify themselves as Yemenis, while the other is that this was a temporal agreement. And that point was pointed out by different succeeding movement struggling against the Saudis, up to our present day by the al-Ḥūtī Movement. As for the British, imam Yaḥyā agreed to recognize British rule over ‘Adan and much of the east for 40 years. That lead to the effective divide of the current Yemen to two states, a semi-centralized al-Mutawakkil kingdom in the north with its capital in Sana’a, and a British protectorate governed from ‘Adan.

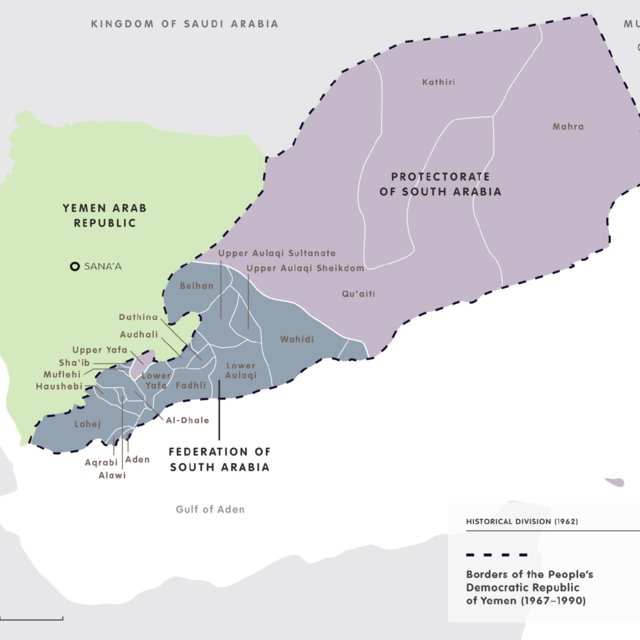

Ironically, while the British could not effectively rule the south and divided it to tiny local statelets, practically a confederation, the conservative northern state in time became ever more dependent of Saudi and British support. Loyalist feared the rising Arab nationalism, while the British and the Saudis fear a new state in the north would restart the quest of ferocious Yemeni tribes for the conceded territories. In 1962 the North Yemeni civil war broke out, where the rebels were supported by Egypt lead by ‘Abd an-Nāṣir, who sought to make a bridgehead here against his main opponent, the Saudis here. Though by 1968 the republican forces practically won, the war devastated the Egyptian army and it was thought wiser to leave Sana’a in the hands of the Yemenis. That is how the Republic of Yemen was formed in the north, but in coincidence with a general uprising in the south, the hotbed for the movement in the north, and the British head to pull out. In result a massively socialist state was created in the south, which came to be known as the the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen.

The two states were mostly were on bad term with each other, mostly due to the fact that the south was highly supported by the Socialist block and being somewhat well off, while the north being traditionally stronger, stayed largely isolated. That mostly overlooked and and forgotten period of the two-state model went on until 1990, when with the fall of the Socialist support unification was made possible. Though southern influence did not diminish, the north lead from Sana’a practically took over the state, under its president ‘Alī ‘Abd Allah Ṣāliḥ, whose legacy continues to haunt Yemen until now.

One unrivaled powerbroker

‘Alī ‘Abd Allah Ṣāliḥ lived an incredible life full of sharp terms until the end and proved to be an exceptionally leader. The newly former Yemen Arab Republic in the North was still fresh when he as a young men was rising through the ranks fast, receiving his first major post in 1977 as governor of Ta‘izz. That proved to a jumping board as a year later his mentor President al-Ġašmī got assassinated and Ṣāliḥ took on. He mercilessly eradicated all opposition to his rule a young and fragile state, where both his predecessors were assassinated. With careful balance between tradition and ruthless power he managed to consolidate control over his family and loyal aids, which created unseen stability in the isolated country. So stabile his rule was that he not only managed to survive, but even lead the unification of the Yemens. Under his rule he managed to use different factions against each other combining privileges to his followers with rigid terror campaigns against uprisings. And those occurred mostly in the south, the remote barren areas in the east and the northern tip by a group later becoming famous, the al-Ḥūtīs.

Ṣāliḥ played similar tactics in the regional scale as well, and though leading a relatively weak state he proved to be quite a tactician. Upon unification he supported Iraq under Ṣaddām, even the invasion of Kuwait, but when that failed he soon changed sides. Much like Sudan at that time, Ṣāliḥ allowed in radical Islamist groups in the early ‘90s, many later became part of al-Qā‘ida, which he utilized against separatists groups and uprising, thus solidifying his rule. The 9-11 incident forced him to course correction, which he once again exploited beautifully joining Bush’s War on Terror officially. By receiving financial support and massive amounts of modern arms he started to crack down on some of radical groups, also some of his local opponents, building up a massive army. And in this quest he even received occasional American support.

His luck was about to run out by the so called Arab Spring in 2011, but ha managed to stall change almost staying power, even backpedaling from the GCC supported power transition deal for immunity. Yet an assassination attempt in 2011 in which he got seriously injured lead him to leave to Saudi Arabia and step down. He officially gave all his powers in 2012 to his long time Vice President al-Hādī practically meaning to Saudi Arabia. Amazingly he spent significant time in the US for medical treatment. But he was still not ready for retirement just yet and once again paved his way for power. This time siding with the al-Ḥūtīs, against whom he fought a prolonged and bloody war between 2004 and 2010, he was the puppet master behind the takeover in early 2015, which eventually lead to Saudi intervention and the war we are seeing now.

Ṣāliḥ himself finally failed in his last turned. Not being able to control the al-Ḥūtīs, nor to bring and end to the war with the Saudis he tried to take one last turned in 2017 siding with the Emiratis, but he was caught and killed. His life proved how difficult is to control such a rebellious country, and his is practically the only leader most Yemenis ever saw, being the only one ever to be elected.

The legacy

Though here one could ask, what is the use of this extensive historical background for our current affairs, it is import to point out that what goes on in Yemen today is not at all entirely new. Yemen as a centralized efficient state hardly ever existed, and in our modern time only experimented with by one president. One nothing less than a true Machiavelli, until his luck finally ran out in 2017.

What we see going on against Saudi Arabia is the same legacy from the wars against the Turks for centuries, and the Egyptians not even that long ago. Against all impossible attempts Yemenis always fought off invaders eventually, and the Saudis are much less capable than their predecessors.

Shiī resistance in the northern highlands is age old, always finding new expressions in different eras. Therefore it does not need outer support, but it is deep rooted in Yemen. And no matter how quarreling and disorderly Yemeni tribal conditions can be, fight against the invader was always a functional galvanizing power, especially as long as it has gains.

All what the Saudi lead coalition managed to take over was the same area once the Turks and British held. Riyadh as well beautifully exploited local resentment against the north, just like Sunni emotions against the Shiī inland. But as the power of the British in time evaporated upon local rivalries, conditions proved to unbearable. And that is exactly what brought about the collapse of the imposed Yemeni vassalage, which now left the Saudis sink in an ever bigger war. A war of attrition no power proved to be capable winning before.

With all these set down, next week we will continue with recent developments. How the Yemenis managed to turn the table around, and now make the Saudis fear for their positions all over.