For quite some time now we hear about protests in many different parts of the third world, from Venezuela to Algeria. Strangely, mostly about oil and gas exporting countries. And while a vast number of analysts like to point out the inner economic and social contradictions of that given country – which is mostly not unfounded at all -, we all seem to skip very casually the main outlying problem. Which is in fact the only real common feature in all of these events. The drop of the oil prices to the lowest level since the Americans invaded Iraq in 2003. Which might just have something to do with the biggest oil exporting country in the world, Saudi Arabia. And if we count back a few years, we can remember, that this is not even a new phenomenon. By the same reasoning Russia’s economic crisis and eventual collapse was forecasted ever since the oil started to drop in 2015. The same year Moscow’s Syrian mission, and Ukraine problems started. And even before, much of the whole “Arab Spring” phenomenon was attested in many instances, like Syria – casually forgotten now – to the sudden drop oil prices in 2009. Strangely, however, a very special set of countries seems to be immune to that recurring problem, the oil and gas producing countries of Persian Gulf. The best friends of the US. But are they really that immune? It seem to be illogical, that the oil price keeps taking very sudden turns, as the biggest oil producing countries by controlling the extraction rate can influence the price. That is the very idea behind the foundation of OPEC. Where the Gulf countries have overwhelming influence. So how come they allow these sudden drops? Even if they seem to be unaffected, surely would not work against their own national interest.

One might lament on this question, but there is another impossible, almost absurd contradiction, which many times trouble even the simplest mind. While the West with Washington in the lead promotes and supports so called democratization movement all over the world, using that theme as sort of ultimate weapon, one very special set of countries seem to be immune to this call as well. Yes, you guessed right! The Gulf countries. Not only they are not being accused regularly about supposed human rights violations or shortcomings in the legal and social practices, which many times even hit EU members states, but they are even being rewarded. Time and again the most absurd thing happen. Just a few sample for it. Qatar in regard to the 2022 Football World Cup was involved in one of the biggest corruption cases of FIFA’s history – that itself is remarkable achievement -, yet not only it was not punished, but could keep hosting the event even after the scandal. Even after shocking news came out, that Doha is building the needed facilities with practical slave work with a total lack of security safeguards. Saudi Arabia, the Emirates and Bahrain are waging a war in Yemen for years by now, which created a humanitarian situation worse than Somalia or Palestine, which is jut appalling. Yet only in late 2018 some EU countries decided to stop exporting arms to Saudi Arabia, casually forgetting the other Gulf states. The result was not international ostracism, but Saudi’s re-election to the U.N. Human Rights Council in 2016, which even made Western human rights groups puzzled. And in the same period until 2021 Qatar, Bahrain and even Pakistan will be members in the same body. Bahrain keeps arresting people for alleged ties to Iran, mostly without any proof. And sometimes for ridiculous charges, like such groups would plot terrorist actions, trying to sink the whole country by “rain bringing prayers”. Yet international criticism is seldom to appear. But the real tip of the iceberg was undoubtedly the Hašoqğī case. Where the Saudi Crown Prince, the de facto ruler of the country Ibn Salmān was directly connected to a direct assassination on foreign soil. Yet again, after few weeks of media outcry, all was forgiven. And here we don’t even mention their immense internal human rights violations, and what these governments committed against Iraq and Syria only in the last few years. Which raises the question, how can these countries cross all boundaries unpunished, even rewarded? Is everything allowed to them? How come, that the most rule breaking players get the most reward? Is their money? Corruption?

These are our question this week. As it is easy to blame this huge contradiction on one factor, the answer is once again deeper. There is a special connection between the leadership of these countries and their employers in the West, which make them rely on each other. The conditions between them not only allow, but to a certain level require and facilitate these huge violations. In other words, what we see as absurd comedy is not some sort of coincidence, but in fact encoded in the system.

Is it all about the money?

The usual first instinct explanation for this strong friendship is money. It is true, that the Gulf countries, primarily Qatar and the Emirates fund robust lobby groups in the US to sweeten their image. Within this project they spend huge sums to the Western press as well, from Washington Post to Huffington Post and Foreign Policy, and that no doubt plays a role why these countries have much better reputation than any other county with similar human rights records. It is very viable, that since these states pay huge sums to the press and lobby groups, they can indirectly influence decision makers. In a world so full of problems, why should criticism target the Gulf states above else while they pay so well? That alone, however, does not explain how this lobby activity is allowed. If money invested was the only tool, we should ask ourselves why others don’t do the same. If Russia, China, Iran or Venezuela for that matter channeled similar sums to the lobby groups, could they achieve the same results? Would they be left alone, or even befriended? The answer is automatically no. They are different, as many would say. But in fact that is the logical order. Foreign policy in states, and by their positions is global policy crafting in the whole global consciousness should not be driven by lobby groups. So in fact, it is not Russia or Iran, but the Gulf states, which are “different”.

Money plays an other, much bigger role as well. Simply we could say, that the lobby groups and the press constitute a human level. Above it, there is a state level. The Gulf states are the biggest arms buyers in the Middle East. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) in 2017 Saudi Arabia was global third in military expenditure with its nearly $70 billion – more than Russia -, and the Emirates with its $24.4 billion was regional second. Putting that into prospective, all other countries among the top ten spenders on arms have major military industry. So when they spend on the military, they create jobs and technology, which they partially sell. The Gulf states have virtually none of that, they are mere buyers. By the same data we can see, that among the top 10 spenders Saudi Arabia has by far the smallest population, while they spend the most – 10% – compared to their GDP. And since they have no real industry or technological infrastructure to build upon it, it is almost guaranteed that they will stay big buyers for a very long time. Now from where these Gulf states by their weapons? Exactly from the West. Meaning they make Western military industry more sustainable, while they contribute to further technological advancements as financiers. That, in theory can backfire. Like it happened with Iraq, where the US sold sophisticated air defense systems in the ‘80s, which caused problems for the US Air Force in 1991. And here Riyadh and Abu Dhabi buy much more and much more comprehensively, than Iraq back at the days. They are not just buying items, but a whole military machine is built by usually very modern Western arms. One sees how these states conduct their war in Yemen, however, can see that backfire is a very distinct possibility. Quite the opposite. Without constant Western resupply and training, and regional auxiliaries like Pakistan, Egypt or Sudan – which do have real fighting capabilities – these Gulf armies are surprisingly ineffective. Under these circumstances it is less surprising why the West does not hurry to stop the carnage in Yemen. Because with the global economy still not fully recovered from the 2008 economic crisis and a new one on the horizon, these sums do matter. Not just as money put into the system, but as jobs, companies as far as technology, food supplies or clothing.

At this point money actually plays a role both in state and personal levels. Two prime example of that are also presented by Saudi Arabia. We can all distinctly remember when President Tump took office, that in 2017 one is first actions was a trip to Saudi Arabia, where he cut a $110 billion arms deal with GCC members states. And that is just the first, immediate slice of a $350 billion cake on the course of 10 years. Though much of the results seriously question just how much is being realized by that, SIPRI’s data show a steady increase. And regardless of the realities, Trump could appear as a huge savior of American jobs that time, and the deal will surely be for his benefit in next elections campaign. The other example is that of Philip May, husband of British PM Theresa May. He works for the very Capital Group, which is the biggest shareholder of BAE Systems, which delivered the rockets used by the U.K. against Syria in its 2017 illegal air strikes, and the second biggest shareholder of Lockheed Martin, one of the biggest arms suppliers of the US. No wonder PM May so vehemently defended arms deals with Saudi Arabia as they are being crucial for the British economy and even safety. In both of these instances we can see, though examples are many, that selling arms to Saudi Arabia and the Gulf is state matter, but also very personal.

Many times the financial link between the West and the Gulf is imaged as an oil business. The Gulf being crucial for the Western industries as study suppliers of cheap, or at least reliable oil. That was undoubtably the case a century ago, when oil sources were much more scarce, but in fact the story in much bigger than that. The US can acquire oil – as it steadily does – from Venezuela, Canada, Mexico or Nigeria. And by now with the growing extraction of shale oil, the US could rely on its own. At least in theory. Europe can, as it does import oil from Russia, Norway and North Africa. So the utter reliance on the Gulf oil, which was a necessity a century ago is by far less binding today. Oil today plays a very different role.

The “lovechild”

All that is understandable from a Western point of view. They are hesitant to leave such a lucrative friendship behind. But why is that so important for the Saudis – and the others in the Gulf -, when this friendship seems to be so one sided. One understands what goes on in Saudi for almost a decade can understand why the Saudis behave this way. And one understands the relationship between the Gulf states can see why the others cannot really break away.

Surely for such a delicate and strong relation to operate it has to be drawn and secured for the long run. That seems to be sufficiently arranged in the West, but the Middle East is not exactly know as a place for long term policies built on predictability. In such a volatile region things can change anytime. That is why for long Saudi Arabia was viewed by the West as in need of firm and straight decision makings. Not like Riyadh was not a firm and unquestionable ally, many times even viewed as a mere satellite. But decisions in Saudi are not of personal, but collective deliberations. And in this case we talk about a huge group. Even the immediate Saudi royal house is around 25 thousand people, which means hundreds if not thousands of princes all in need of jobs. Some indeed took it to the private sector, but the majority got public positions. And the bigger Saudi clan is even much bigger. In this vast network tribal considerations do matter a lot, where a careful balance has to be kept between the sections of the royal family and the attached houses. In this system of selective appointments and patronage by older members of clans there is a constant rivalry. No major decisions can be made, even by the king without previously gaining at least acknowledgment by the elders of each section, who usually hold high positions. So if the Saudi ship turns, that is the will and the work of dozens of elders and hundreds of princes. While elected bodies don’t exist and accountability is almost meaningless, and this is indeed an absolute monarchy in every sense of the word, it is still not run by one person. That model was refurbished to the practical control of one man by now, Crown Prince Muḥammad ibn Salmān. But how?

The 1985 born Crown Prince is in many ways unusual among his relatives, the other potential candidates for power, thought seemingly not for his advantage. Unlike most Saudi and Gulf royal children, he never studied in the West, only has a BA from a Saudi university. He never pursued a military career either, like most of his relatives, but tried his luck in private businesses. How that went is hard to know, but sometime around 2005 he quit and became the personal secretary of his father, the now king Salmān. That is significant, because as his closest aid, he gained insight to those NGOs, officially charitable organizations, which were run by Salmān for decades, and which were many times suspected to sponsor extremist, even terrorist organizations. Which were all well know for American intelligence services, because that was the funding model for Afghan insurgency against the Soviets in the ‘80s. One famous example is the Saudi High Commission for Aid to Bosnia. Salmān was also governor of Riyadh province, being one of the most prominent power brokers of the family. That is the real education of Muḥammad ibn Salmān. In 2009 he took over Riyadh province from his father, and became a minister. That is when he started to grow in position.

Now in the Saudi model, to achieve bigger stability as there is no official law of royal inheritance, there many titles, which are merely preliminary for bigger positions. If the king dies, automatically the Crown Prince (walī ‘ahd) becomes king. His position is filled by the so far deputy Crown Prince (walī walī ‘ahd). This secures, that even if the new king would die soon after ascension, there would be someone to replace him immediately. Right after the ascension, however, the royal Court of Princes gather to chose the new deputy Crown Prince. Therefore family connections are respected and collective decision prevails. Usually the king should have no word in this election.

In 2011, however, this system was broken by unexpected events, and for the great luck of Muḥammad ibn Salmān. Crown Prince Sulṭān ibn ‘Abd al-‘Azīz died that year, and as Nāyif ibn ‘Abd al-‘Azīz – deputy Crown Prince that time – took his place, Salmān was chosen as new deputy. He became second in line. Yet only after a year Nāyif died as well, and Salmān became Crown Prince, while Muqrin, the youngest surviving son of the state founder, king ‘Abd al-‘Azīz became the new second in line. Salmān’s personal advisor and closest ally by then was already Muḥammad ibn Salmān. In 2015 king ‘Abd Allah ibn ‘Abd al-‘Azīz died, and Salmān, who was not even on the royal inheritance five years prior became king. He personally appointed his son to be deputy Crown Prince, which was a total disregard for the unwritten rules of the state. But since the decision could be revoked once Muqrin would take power – as Salmān was not expected to live long -, that step was not opposed. Yet only after a few months Salmān relieved Muqrin, and appointed his own nephew, Muḥammad ibn Nāyif as Crown Prince. That was totally out of convention and marked a shift from collective decision to a more direct rule. At the same time the new king appointed his son to be Minister of Defence, the youngest in the world that time. Muḥammad ibn Salmān soon tried to prove himself, and as what seemed to be an easy victory, he called for a collective GCC operation in Yemen. Formally against the Ḥūtī movement, and in defence of the former Yemeni government ousted by it. The reality was, however, that king’s rising son wanted to prove himself as a capable decision maker, and started a war for his own prestige. It was so much his personal decision, that even the head of the Saudi National Guard – most responsible for direct military matters – Mut‘ib Ibn ‘Abd Allah and much of the intelligence chiefs were cut out. That decision, as we can clearly see it by now, was a devastating mistake, which is still attriting Saudi resources. As his power was rising he made considerable enemies within the royal family.

In June 2017 Muḥammad ibn Salmān rose even more, as his father ousted Crown Prince Muḥammad ibn Nāyif, appointing his son instead. What is even more surprising, is that the deputy Crown Prince’s position was left vacant, as it is to this day. From that day on Muḥammad ibn Salmān started to practically rule the country as he was the monarch himself, and started a grand purge. Officially the program was run under the title of anti-corruption, but the nearly 200 businessman and notable of the country, mostly other princes from the royal family was his practical opposition. Most of the people who fell victim of the purge were arrested, allegedly tortured and only released for a huge sum of money. Thought official court procedures were not started against any of them. Such notable figures fell victim to the move as Mut‘ib ibn ‘Abd Allah, former head of the National Guard and Walīd ibn Ṭalāl, co-owner of the Four Seasons hotel chain. Many princes were, however, outright executed, some by shooting down the airplane carrying him. The purge was notoriously savage, but seldom caused any diplomatic criticism. News sources also reveal that around that the Crown Prince created a special secret task force to crack down on any opposition against his consolidation to the power be it in the country or abroad. The head of this alleged crack force is Sa‘ūd al-Qaḥṭānī, the main suspect in the Hāšoqğī case. Which seems to be only one of the many crackdown operations.

So within a very short period of time, almost ten years, Muḥammad ibn Salmān rose out of complete obscurity and his ascendence to power completely reshape the power elite and the unwritten rules of Saudi Arabia. When his father dies, he will not only became king, but – given it is successful – will solve a longstanding dilemma of the country. Which is the long due generational change. Ever since Saudi Arabia was created – actually the third one – it was ruled by the state founding king, ‘Abd al-Azīz and his sons. Among them the two last living ones are the king Salmān, and the ousted former Crown Prince Muqrin. The new generation, that of the grandchildren of ‘Abd al-‘Azīz are very different from their fathers, as they did not grow up in poverty and religious austerity. They are the generation of the immensely rich kingdom, where the court already lived a very lavish lifestyle, and had education in the West.

What is remarkable, that the US, which has military bases in Saudi Arabia, and has very intimate security and military ties with Riyadh watched that complete reshaping of the state with remarkable ease. Even protected the Crown Prince, when scandal hit him in the Hāšoqğī case. Which is a clear sign of approval. That would indicate, that these steps are not only acceptable for Washington, but this firmer grip of power is in its interest.

The value of Riyadh

As mentioned before, Saudi Arabia plays a pivotal role in the Gulf. As many interviews and commented approve even by the Qataris now at odds with Riyadh, that Saudi always played a special role within the GCC. As sort of older brother, or power broker. Their connection is very strong to the Emirates, especially since a very similar procedure like that of Muḥammad ibn Salmān happened there, as over Muḥammad ibn Zāyid took practical control of Abu Dhabi. Consequently the Emirates. Also as a nominal Crown Prince. Since 2011, the outbreak of the so called Arab Spring Bahrain is occupied by Saudi forces. That occupation is the main reason why the Sunni Bahraini royal family is still in power, despite huge outrage of the mostly Shia population. Oman was always having much stronger relations with the UK, than with the US, and in regional politics they always tried to be a conciliatory force, not to dedicate itself to any sides exclusively. Kuwait, especially since the Iraqi invasion is mostly concern with its own security, and therefore goes along with any Saudi decisions. Though in many significant decisions they chose to stay out. Qatar was the only state, which tried to create a policy of its own, but since 2017 links between Doha and Riyadh are irreversibly severed.

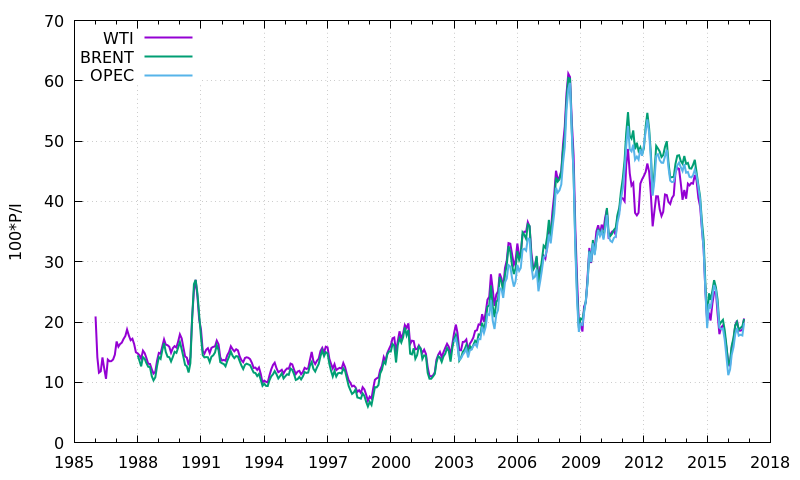

That means, that whoever controls Riyadh, practically has control over the Gulf’s small states in one way or another. And here, as indicated before, oil plays a special role. Saudi Arabia, the biggest OPEC member is constantly increasing oil output for the last six years or so. Mostly by American pressure. That is practically the only member country to do that, because that pushes the prices down. This actually so harmful even to the Saudi economy, along with the war on Yemen, that Saudi budget is in deficit for years. In response to that, to cut the deficit, they pump up the oil sales, which cut prices and even severs the deficit. Even Gulf countries criticize this policy for years now. One logical way to cut deficit would be to cut the military budget. For that stopping the war on Yemen would be a good start. Instead of that, Ibn Salmān’s cure seems to be to sell the most valuable assets in a massive privatization program, in which Aramco is the biggest, but far not the only cake. It seems, that today Riyadh does everything against its own interests. Almost in a suicidal way, and no wonders many panic. Like Qatar, which now much less in the hands of the Saudis already announced its wish to quit the OPEC in December 2018.

A more complete picture

So what really happens is a twofold development for seemingly mutual benefit. One man, or a small branch of the Saudi family managed to get American backing to consolidate power and create a more direct rule. At the same time Riyadh in creating coalitions and alliances, by which gets a more direct control in the Gulf as well. Qatar seems to slip out of hand, but even if only four states stay under Muḥammad ibn Salmān’s realm, that is considerable.

But what the West, and most especially the US gets in return is more than a steady market for arms, or as President Trump put it in his election campaign, “a milking cow”. Many analysts, even in the Arab world seem to agree, that America is steadily leaving the Middle East and concentrates on other parts of the globe. Though I would argue, that many notions seriously question this, but even if we accept it, the Gulf would be a significant price in anyone else’s hand. Because the oil price played a significant role in the American strategy in the last decade, irrespective of the actual administration. Russia experienced a significant loss of income, and was expected to yield in a number of questions to American demands. The same drop of oil prices caused deficit to Iran, also at odds with Washington. That, combined with the renewed sanctions clearly aims to bring about system change in Iran, as John Bolton forecasted even before he became National Security Adviser. And now Venezuela, which is experiencing severe economic crisis. For which all the Western channels, casually forgetting the American sanctions, point to only two factors. The inefficient and corrupt government, and the unexpected drop of oil prices. And why is the price so low? Because Saudi Arabia keeps increasing the output, creating an unreasonable surplus, even against it own national interest. So with Riyadh in hand, Washington actually has a handle on the oil tap. Not really its own access to oil is significant, but having the biggest producers tightly controlled, it can regulate the price. Which is almost as capable weapon as the US Army.

This scenario is not new at all. In Saudi Arabia there was only one king, who dared to oppose Western policies in the Middle East. He was king Fayṣal (1964-75), who in 1973 caused the first oil crisis by withholding Saudi oil from the market in response of Western support for Israel in that year’s third Arab-Israeli war. The move, clear opposite to what Riyadh does now, actually skyrocketed oil prices so much, that it founded the oil riches of Saudi Arabia. Strangely enough, he was to only Saudi king to die a violent death, only a year after the oil embargo, killed by one of his nephews, who just returned from the US. What is even more remarkable, that at that time the only reason why the American economy did not collapse because one country suddenly just did, what Saudi does today. Meaning flooding the market with oil, even by destroying its own economy. That state was Venezuela.