Last week we took a detour from our topic started two weeks ago about Yemen. That was a decision well in place, since there was a turning point in the struggle of the liberation of Northern Syria. A topic now rapidly losing international attention, and not only for the Corona virus now ruling the headlines, but also because so far the agreement made in Moscow between Erdoğan and Putin is so far holding. Holding, thought the reports are varying, just like the Turkish statements about it, whether Turkey is indeed pulling its heavy armaments out of Idlib, or not. But for the moment Syria is celebrating the gains and the ceasefire is mostly standing, regardless the sporadic breaches by the terrorist factions.

In turn, however, it also proved to be a good decision to wait just a little longer with the developments in Yemen, since much is going on, and there are great changes about to happen in this scenery. Which all together with the changing atmosphere all over the Arab world now, might just prove to be another nail in the Gulf supremacy’s coffin in the region.

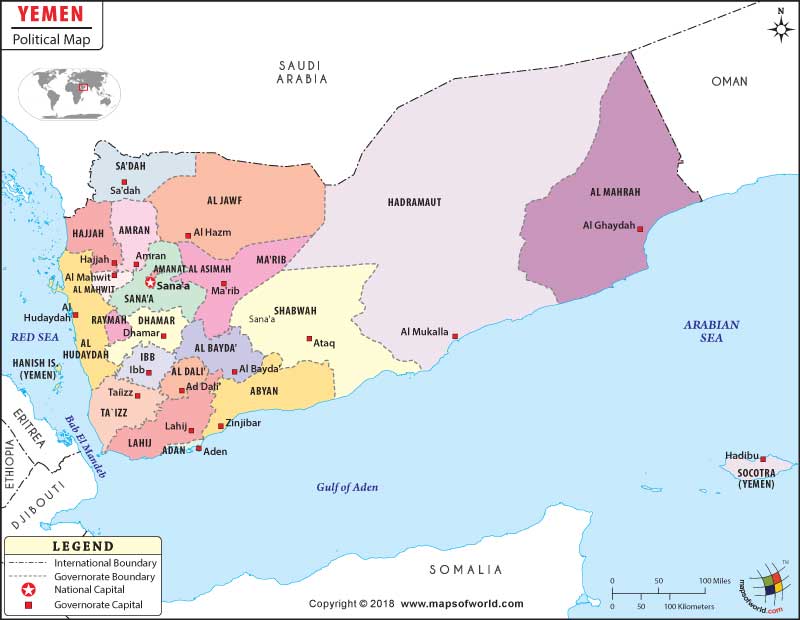

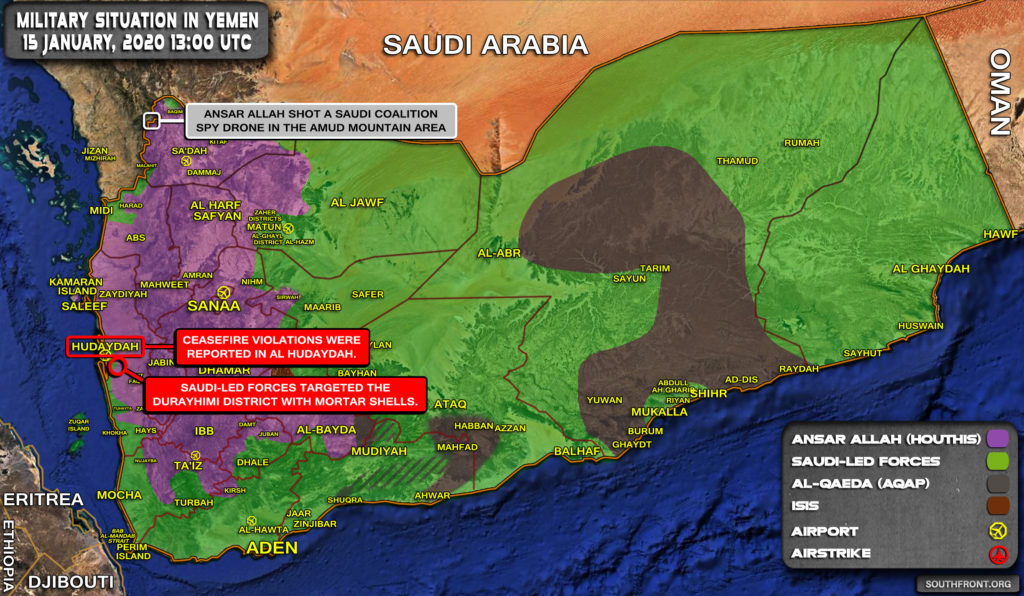

This very Gulf supremacy, lead by the Saudi-Emirati and the Saudi-Qatari tandems back then, which was the biggest beneficiary of the so called “Arab Spring”, some eight years ago was on the doorstep of turning Yemen into client state completely under their control. That, however, started to slip out of their hands some six years ago, and mostly due to internal reasons within Saudi Arabia that time, and reasons of rivalry between the Gulf partners, a so called “International Coalition” was formed to launch a war in Yemen. Through with the course of this war, which brought immense suffers to the Yemeni people, the Coalition lost most of it members mostly just retaining its name as international, and only managed to keep certain parts of Yemen historically at odds with Sana’a under their influence. So far they “only” could not win, but they were very far from defeat. Yet the obsession with this folder gradually caused it to be the epicenter of a crisis, which drains huge assets from Riyadh and Abū Zabī, made them struggle all over the regional board from Libya to Sudan, and which now causes grate rifts within the Saudi family itself, and now the whole domino is turning. A new phase has started in the conflict, which the Saudi-Emirati tandem don’t seem to be able to contain, and which might just very much bury the supremacy of this tandem under itself.

What really went on in the last few years in Yemen, and how it all started? What is changing now, and is the fall of al-Ğawf Province the end of the battle, or just the beginning of a much bigger transformation? And how it all hits now back to the Saudi internal politics? These matters will be our main interests. However, since this is a wide topic and things are still in motion, in a hope to see even further results by next week we once again decided to split our assessments, and leave much to next week for the continuation.

The war. How it all started?

Since much of the Yemeni war and its origins in the confusing days of 2011 are well documented, and since we have more direct matters to assess we only with to highlight the key points to give an overall framework to the now changing realities. Thought the busy days of 2011, when ‘Alī ‘Abd Allah Ṣāliḥ was masterfully maneuvering to save his post is a true testament for his political genius is especially lightly touched here, as it has little directs effect to the current reality by now, especially since his death.

As the “Arab Spring” reached Yemen the pressure was growing in President Ṣāliḥ as well, by then being president for 36 years all together, and more than 20 for the unified Yemen. His lengthily efforts to evade the change came to an end in by an assassination attempt on 3 June, which left him burned, after which he took medical care in Riyadh. And here started a careful relation between Ṣāliḥ, the Saudis and the Emiratis, all trying to outsmart the other. This link, especially by now might seem strange, but for long the only relatively constant supporter of Ṣāliḥ’s isolated North Yemen, and later on the unified state was the Emirates lead by Zāyid ibn Sulṭān. Which at that time, unlike now, was a galvanizing force in the Arab world. This link survived Sheikh Zāyid’s death in 2004 and stayed strong under his son’s, especially that for long the puppeteer qualities of Muḥammad ibn Zāyid did not show. That is one of the reason why Ṣāliḥ trusted these partners, at least to a certain point. He returned from Yemen later that year, but could not control the situation and on 23 November signed the U.N.-GCC supported power transfer deal.

By this he would transfer all his powers to his Vice President Hādī, who was for long a figurehead member of the ruling elite symbolizing that the South has influence in government, since Hādī started his career in the South Yemeni army. In exchange for this, while still holding on to his title for a limited time, Ṣāliḥ would enjoy immunity, would not be excluded from further political action, and elections would be held early 2012. All that happened and in 2012 Hādī won the elections, though he was the only candidate. Which is believed to make him the legal president up until now. However, the deal and all later agreements specifically marked that all this is to aim a more complex power transfer. Hādī would only get a mandate for two years, during which a new constitution would be drafted and voted upon. With that at the end of 2014 being the latest new elections would be held in all levels.

Hādī’s initial time was paralyzed by Ṣāliḥ still staying in office and interfering, only slowly understanding that the deal was not a formality for his feeble second, but the overtake of the foreign “allies” using Hādī as a tool. At that point he started to look for an alternative solution, and the most capable was the growing Shiī resistance in the north. In these chaotic year as Hādī and the powers behind him tried to assert control, both Dā‘iš and Anṣār Allah was gaining ground, the latter mostly in the north closing on the capital. On 21 September 2014 they took over the capital practically without resistance, but keeping Hādī and the parliament in office, forcing upon them a hard coexistence. All this had much to do with Ṣāliḥ paving the way to get back into power. On January 20 Anṣār Allah seized control over the Presidential palace, and thought did not hurt the president and acknowledged him in his office, it imposed its Supreme Revolutionary Council as government.

That was indeed an unlawful act, but by that time there was no legal government either, as the President, the Parliament and the government all lost mandate by the end of 2014. Nonetheless for the time being the new Revolutionary Council using much of the support of Ṣāliḥ old party members and supporters of the military recognized Hādī as president, and tried to force out the Saudi allies. Right at that time, however, as we shall see later, major shifts happened in Saudi, which further complicated matters and the pressure was growing on Hādī to leave Sana’a and seek support. On 21 February Hādī resigned and escaped from Sana’a with Saudi-Emirati intelligence support and arrived to ‘Adan, which practically left Anṣār Allah in charge, which indeed could take over much of the country and could have paved the way for Ṣāliḥ to retake office. That, however, was not to happen as in ‘Adan Hādī revoked his resignation, reclaimed his already terminated mandate and officially asked for foreign intervention. On 26 March Operation Decisive Storm was launched by a broad coalition of Arab states being supported by the US officially and a number of other Western states unofficially as arms and intelligence providers. Though that operation officially ended a month later, consolidating Hādī in the south, in 22 April 2015 it was immediately followed by Operation Restoring Hope, lasting until its very day.

The war, which was for long concentrating on massive areal bombardments to dislodge Anṣār Allah from the capital and brought on an almost complete lockdown of Yemen went back and forth, all hoping to gain the upper hand with winning the majority of support. Anṣār Allah was mostly betting on Ṣāliḥ’s support, while the Saudis tried to impose the Iṣlāḥ [Reform] Party, the local branch of the Muslim Brotherhood into power, which also centered in the northeast. The war, which devastated Yemen and caused a total humanitarian catastrophe, where famine as long defeated diseases decimate a population, reached a stalemate by 2017 heighten side being able to overcome the other. By that time Ṣāliḥ realized that he cannot return to office and his original gamble for a fast takeover was lost, which made him try to change sides once again. Having failed in that, he was killed by fighters of the Anṣār Allah. The war nonetheless went on, but by than Anṣār Allah inherited most of Ṣāliḥ’s former power base, especially after his brother was also killed.

In November 2018 Operation Golden Victory was launched by the Saudi forces to capture al-Ḥudayda, the biggest port still in al-Ḥūtī control at time, being the biggest support channel. While it is disputed how much military support the government of Sana’a was getting here, it was known that most of the humanitarian aid entered Yemen here, which was indeed a lifeline for the government. The battle lasted all month, making the city practically divided and that lead to the ceasefire deal in Stockholm in December 2018, which is officially still standing and not just for the city. But by mid 2019 most Coalition members withdrew al-Ḥūtīs stabilized themself. In the last few weeks, they started to advance once again, but after several strikes deep into Saudi territories – mostly our topic next week – it offered a one sided ceasefire for negotiations. Which so far Riyadh is reluctant to take, but soon might jut be forced to accept, as the tip of the balance between the two illegitimate governments are changing for the benefit of Sana’a now.

Assessments on the Yemeni war differ greatly around one key question, mostly even without touching, or even realizing the magnitude of the matter. Who represents the Yemeni government? In one hand, mostly in Western and Gulf or Gulf sponsored sources the legal Yemeni government is lead by President ‘Abd Rabbihi Manṣūr Hādī, a former loyal servant and Vice President (1994-2012) of ‘Alī ‘Abd Allah Ṣāliḥ. That is now residing in exile in ‘Adan and being supported by the “International Coalition” against the al-Ḥūtī insurrection usurping power in Sana’a, that being the extended arm of the Iranian sphere of influence or proxies in the region. On the other hand, a principle adopted mostly by those in opposition of Saudi policies, ‘Abd Rabbihi Manṣūr Hādī lost legitimacy having exceeded his term and even resigning and has since than became a tool of open Saudi-Emirati intrusion into Yemeni internal affairs. In this sense the Yemeni “Salvation” government, a broad umbrella mostly, though not entirely inheriting the former Yemeni state is the legitimate representative, in which the Anṣār Allah Movement lead by the al-Ḥūtī group is an important component with its military arm, the Popular Committees. Indeed the question is not an easy one and in all fairness in one hand it is true that government now in Sana’a inherited more from the former central Yemeni state apparatus, it is more concentrated around one principal group, and the whole matter is much rather a reawakening of the age old contradiction between North and South.

Either way, however, it is clear to see that the al-Ḥūtī group is a key protagonist in the story, either as the leading force in the liberation of Yemen from Saudi invasion, or a key Iranian proxy usurping the central authority.

In many ways the al-Ḥūtī tribe, family, group and movement is a modern representation of the same Zaydī Shiī movement that was strong in the northern mountainous region for centuries and which was leading the state from time to time, or leading the struggle against foreign invaders. After Imam Yaḥyā Ḥamīd ad-Dīn al-Mutawakkil and the gradual disintegration of the al-Mutawakkil kingdom the new, mostly republican-Socialist tendencies won over the political scene and the religious-Conservative representation of the Zaydīs lost influence. This had much to do with the fact that the one unrivaled power master ‘Alī ‘Abd Allah Ṣāliḥ was also from the north and had his ways to gain support. This state of political-ideological paralysis lasted until the 1990s, when much of the influence of the Islamic Revolution in Iran and the victories of Ḥizb Allah in Lebanon against the Israeli invasion found an audience in Ṣa‘ada province, the bulwark of Yemeni Zaydīs. In 1986 the “Ittiḥād aš-Šabāb – Union of the Youth” was formed, which is believed to be the most direct predecessor of the current movement, and which entered the political arena after the Yemeni unification in 1990. It was first organizing itself among the youth, especially in the north and taking inspiration from Iran and Lebanon. Though it is claimed, and indeed the mental and moral support between Ḥizb Allah, Iran and the al-Ḥūtīs are acknowledged, direct financial, or military links have never been verified, other than the al-Ḥūtīs do indeed copy pro-Iranian groups in style and slogans a lot. But as we saw in our last article on Yemen, Zaydī radicalism has a long history in the north of Yemen, therefore it might just as well serve as a spiritual catalyst.

The first main leader of the group was Ḥussayn Badr ad-Dīn al-Ḥūtī, a descendant of Zaydī religious leaders, who with his family allegedly spent considerable time in Iran, and have developed good personal ties with Iranian state and religious leaders, as well with prominent members of Lebanese Ḥizb Allah. The slowly emerging group first aired concerns of negligence for the region, but soon gained support by attacking the Saudi influence gaining upon the Yemeni state, and the decisions of the government siding with the West in various matters. Which was at the time a political necessity for ‘Alī ‘Abd Allah Ṣāliḥ having been a strong supporter of Iraq in the 1991 invasion of Kuwait, and facing a deadly civil war after the unification until 1994. This tension, only one and at the time one of the smaller ones for the Yemeni President, got especially strained after the invasion of Iraq in 2003, in which Sana’a was a supporting partner. By that time the al-Ḥūtī group was renamed as aš-Šabāb al-Mu’minūn, Believing Youth and had support was bigger larger than the boundaries of the home province. In 2004 huge rallies were organized even in Sana’a renouncing the support for America and chanted slogans most familiar from Iran, Death to America. That in time became incorporated to their main slogan: Death to America! Death to Israel! Curse to the Jews! Victory to Islam! President Ṣāliḥ was responding in his usual fashion by a massive arrest campaign in the capital, but being a careful tactician and sensing the influence of the group, he did not chose attack head on. He summoned Ḥussayn al-Ḥūtī to the capital to reach an agreement, but when he refused a series of clashes erupted lasting for several months between central troops ordered to deliver him to Sana’a and his followers, which lead to Ḥussayn al-Ḥūtī’s death. A matter even a decade late was a source of great controversy.

That, however, did not cripple the movement as it was taken over by his brother, ‘Abd al-Malik, who still leads the movement called Anṣār Allah, where his other brothers are all prominent members. In many ways even more prominent, as ‘Abd al-Malik is more of spiritual figurehead as a charismatic leader like his brother Ḥussayn was. And this is the starting point from where on the al-Ḥūtī group very specifically distanced itself from any notion “al-Ḥūtī”, signaling that it has a much larger appeal than a tribal allegiance and indeed managed to gain in years to bring significant Sunni support. The constant “al-Ḥūtī” reference concentrates on the idea that this is a tribal-family group only, therefore highly limited in appeal, consequently in numbers.

The reaction was a war erupting between the state and the al-Ḥūtīs, which lasted until 2010. In yet another beautiful maneuver ‘Alī ‘Abd Allah Ṣāliḥ exploited the Saudi fears from an emerging Shiī group and not willing to sink into a prolonged war alone in a notorious hazardous and fanatical frontier he invited the Saudis. Which they did, and that was the first time the Saudi army faced this foe, even with considerable Yemeni support, which lead to catastrophic defeat. Less of Ṣāliḥ, who could benefit from this internally and financially, but much more for the Saudi army suffering humiliating defeats, when entire battalions were scattered and the most modern equipment taken away, like the famed Abrams tanks. A scene repeated many times after 2014. The war went back and forth, but by 2010 Ṣāliḥ mostly turned the table and on February the 2010 the sides agreed to a ceasefire, which crippled Anṣār Allah, but did not exterminate it. ‘Alī ‘Abd Allah Ṣāliḥ’s victory, however, proved to be short lived, as only less than a year later he was struggling for survival in the Arab Spring. In which, not surprisingly, the Anṣār Allah was an important organizer.

Taking advantage of the general meltdown of the central authority, but also not wishing to let the state be taken over by pro-Saudi forces, Anṣār Allah joined and organized the protests. Which payed off as they were part of the process removing Ṣāliḥ from power in 2011 and in 2013 they joined the National Dialogue Conference, which sought to find a solution for the transition of power and envisioned a federal model for Yemen. Though Anṣār Allah rejected the stipulations of the process, it was by than an officially recognized political actor, not a renegade group anymore, and their influence was gradually growing all along the north, slowly gaining unofficial control over most of the northern provinces, including the now regained al-Ğawf. Though they renounced the original U.N.-GCC deal of transition, they acknowledged the legitimate process. However, in during the time of uncertainties between 2011 and 2014 as central authority collapsed and radical groups including Dā‘iš, many of whom already had a level of control over segments of the country, started to gain foothold. In part because of that, and in part to further their own mission, Anṣār Allah was expanding and arming itself heavily, being only one of the competing forces ready for takeover. It is significant, however, that during that time their biggest opponent was not the central authority, but the than growing Islamist terror groups.

In sum, therefore, Anṣār Allah is much bigger than a simple tribal federation, upon which it was founded. It grew into a massive networks, including many Sunni groups, which by now successfully incorporated many of the Yemeni state attributes. The nucleus of the movement is indeed al-Ḥūtī family and tribe around it, but the movement by now slowing distancing itself to incorporate larger spectrums of the former state bodies. Which, mostly by the rival state structure falling apart, is successful. Here we much rather see a dual structure, in which the al-Ḥūtī group and movement serves a religious-ideological core catalyst along a broader movement, much more focusing of ethnic Arab themes, than religious one. By now the government of Hādī has practically fallen apart, and after his escape and putting his capital in ‘Adan, since Hādī himself being from the south, his government gained an appearance of being the revival of the former South Yemeni state – that being always renounced by Hādī -, which now works for the benefit of the Salvation government, operating with themes as the unity of the state and protection from foreign invasion.

Therefore the sheer categorization of the Salvation government, the Anṣār Allah and the al-Ḥūtīs is pretty much the matter itself, far greater then being scientific effort.

The price of Yemen

Probably the most logical question for anyone new to the topic of the Yemeni war is to ask, what is the war going on for. What is the price of Yemen? Officially Saudi Arabia and the Emirates in the colors of the “International” Coalition fight to restore legality and order in a friendly neighboring country, and to free it from Iranian proxy influence, which might in time threaten the security of the region. Though semi-officially the goal is to assure the gains of the U.N.-GCC agreement of power transition, which would put a loyal ally in charge of that neighboring country.

With any sense of reality, however, none of these are convincing arguments, even if we accept that Anṣār Allah would be an Iranian proxy. Not because this movement has showed signs of reasoning and honored agreements, therefore even in a full takeover an accord could be reached, since then it would be a bargaining tool for Iran in bigger disputes. Much more, because the whole history of Yemen proves that no group can rule firmly over the whole Yemen by force, therefore the Anṣār Allah would be much to preoccupied to run Yemen, than to pose any real threat. Also, it is one thing to fight off an invasion on home ground, but it is another to take a war abroad. It is true that Yemenis showed interests to areas under Saudi control now, even to the holy cities, but in the current state of Yemen rebuilding the country would be a bigger burden for the Anṣār Allah than they could carry on an invasion, or a prolonged war. Than they would have to deliver achievements, otherwise they would lose support fast. And indeed all the Saudi claims are hard to find logical, knowing how huge funds are wasted in this project, apparently without any gains, nor even tangible goal. After all, even if the Coalition won and Hādī would return to Sana’a, what would be the benefit for Riyadh and Abū Zabī?

The efforts and the assets spent here indicate a significant price. Something beyond direct material gains, or those concentrating in very small sections, since the intensity of the Saudi-Emirati campaign hardly changed with gains and losses.

The closest possible answer that the aim is a set of direct gains on the ground and internal goals, all different for each individual party. First off all Yemen has natural resources, mostly oil, though its reserve are nothing compared to those of Saudi Arabia, or the Emirates. So that can hardly be the answer. The most direct gains are due to the strategic location of the country right at the southern exit of the Red Sea. In this regard the Socotra archipelago has an even bigger significance, where the rivalry between the Saudis and the Emiratis are the most intensive. Whoever has bases here, has an overview of the movements in the Red Sea, along the coasts of Somalia, to Egypt and has control over a segment of one of the world’s most precious trade routes. The competition for this strategic piece of land is probably best signaled by the fact that Djibouti hosts four foreign military bases – the US, China, Japan, France and Italy -, Eritrea three – Iran, Israel and the Emirates – and in Somalia two – Turkey and the Emirates. Meaning there is a stiff competition here and whoever has a foothold in Yemen has a valuable real estate. There is, however, large and so far practically untouched oil reserves around Socotra, which on its own is a unique natural phenomenon, highly exploitable for other purposes as well. Most of the untouched oil reserves are under Yemeni waters, which according to recent relegations the Emirates carefully assessed since 2016, and has an immediate reserve of some 5 billion barrels, which Abū Zabī already started to extract

Yemen, however, has another resource, practically only exploitable for Arabs states. That is manpower. Not only the massive numbers of workers have for long flooded the Saudi and Emirati labor market with cheap and very reliable workforce, but Yemenis are well recognized fighters. That is a capability famously missing in the Gulf’s power arsenal, which makes Yemen an excellent pool of recruits. Not directly for the Saudi or the Emirati Defense Forces, thought such detachments are possible to create, but for radical elements well known to be used as proxies by these states. Like the ones deployed in Syria and Iraq in recent years. Having a friendly government in place, Yemen can be turned for area of ideological advancement, which in time yields bigger number of capable fanatical fighters than Syria, Iraq or Libya ever did. And since Yemenis for outsiders are hardly distinguishable by appearance and speech from the Gulf people, the secondary use of these fighters is possible.

These could have been the original motivations to promote a takeover and a strong influence, but the reasons for direct military involvement still lasting today are much more linked to direct personal ambitions of emerging leaders in the Emirates and in Saudi Arabia respectively. In an earlier article we already showed how Muḥammad ibn Zāyid used the war in Yemen to consolidate his grip on the other six emirates in the UAE, and with much success. Which is perfectly enough reason. Having achieved most of that, especially by gaining ever bigger influence over Muḥammad ibn Salmān, consequently over the Saudi policies, and having felt the limits by Dubai, now the Ibn Zāyid slowly withdraws now, for much bigger concerns. As for Riyadh, if we look back to early 2015, at that time now Crown Prince and practical head of policies Muḥammad ibn Salmān was at that time only a young Minister of Defense, as his father only took the throne January that year. He managed to take the post of Secondary Crown Prince in April 2015 and only two years later he became the Crown Prince – without Secondary Crown Prince in an unprecedented move – sidelining his much more capable cousin, Muḥammad ibn Nāyif. This period of being second to Muḥammad ibn Nāyif for long haunted Muḥammad ibn Salmān, as the opposition centered around his cousin. Which after several brutal crackdowns was met with a severe blow, as Muḥammad ibn Nāyif was arrested to prevent a coup. By now we forget that Muḥammad ibn Salmān rose to power in an unprecedented speed in Saudi Arabia only few years ago, in which his position as Defense Minister and being mostly responsible for the position taken in Yemen had a major role. Ironically the move was supposed to increase and stabilize his standing, but his failure showed him a valuable asset for those who wish to gain influence over Riyadh. One being the US, for which the Hašuqğī incident is just one prime example, but even for Muḥammad ibn Zāyid, ruler of the Emirates, who is directly behind the recent shakeup in Riyadh. Ironically the war still works for his benefit, as if tomorrow he takes the throne and withdraws from Yemen, he will be the peacemaker in a war he started in the first place. Overall, however, especially in the early years of his carrier from 2015 to 2017, the war in Yemen was a very significant political jump post for the now Crown Prince, especially since at that time the losses were not showing and progress could be projected.

Losing the supremacy?

With Saudi sinking ever deeper into this conflict the cracks within the royal families started to show, which only this week lead to a series of arrests. That might stop the tear for now, but cannot save the plummeting economy as the stock market reaches a record low.

With the Gulf being occupied with Yemen, which seemed like an easy assignment five years ago, signs started to show that this might be the end of the Gulf supremacy that stated a good decade ago culminating in the Arab Spring, with the reincorporation of Syria into the Arab League.