The theme that was ruling the Middle East news for a month now, the full normalization of ties between Israel and the United Arab Emirates under American supervision has finally been signed. The agreement, which came to be known as the “Abraham Accords Peace Agreement”, and to which after much-failed attempts Washington and Abū Zabī even managed to force Bahrain into was a grand spectacle. For some, it is a tragic turn equal to treachery, and the marks the beginning of the implementation for the dreaded “New Middle East” policy. For others, it is the beginning of a new area promising peace, but at least a major rearrangement of the Middle Eastern chessboard. Either way, this is a historical milestone though probably not the way Trump has envisioned it, as for him it was a campaign extravaganza above anything else.

The signing ceremony was a clear depiction of what this really is and in a number of humiliating ways. It was clear to see that unlike all agreements before, like the ones with Egypt, or Jordan, or even the one with Mauritania and the infamous Oslo accords this was not a pact made by equal partners under American oversight. Not even by sight. While on the American and the Israeli sides the actual leaders of the countries signed the accords, in the case of Bahrain and the UAE nor the nominal rulers, nor the de facto leaders of the countries were present. Instead, their foreign ministers signed the accords, who are in fact relatively low figures in their own respective power structures.

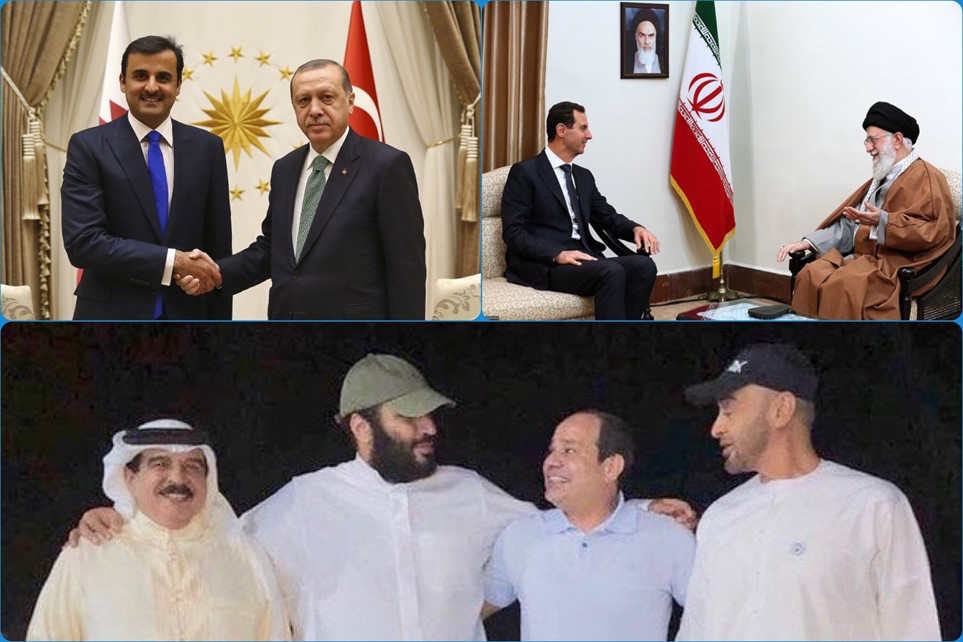

This scene has its importance, but our focus is not that, as there are many detailed assessments on this topic. After what we suggested few two weeks ago about the Israeli-Emirati strategic partnership, what was specifically highlighted in the Abraham Accords paragraph 7 under the title “Strategic Agenda for the Middle East”, this is unfolding in many layers now. It shows in Yemen in the joint project of the island of Socotra, in the Emirati mediation to include more and more Arab states to the deal, and now in the Palestinian fold, as Washington is ready to endorse the UAE’s man to be the next Palestinian president. What was aired directly in the Israeli press. With this development the camp so far seemed to be the weakest, the Emirati-Saudi-Egyptian Axis managed to get ahead and now looks to be on the winning side. Which understandably triggered a response in the other two main camps. They have to cooperate in one way or another to cope with this development, but this needed cooperation, about which Iranian president Rōḥānī spoke very clearly recently, has a number of obstacles.

This week Panorama focuses on the three main strategic camps in the Middle East, how they are made up and what are their aims, and how much the Abraham Accords changed the equation, triggering responses. In many ways this is the culmination of many themes we have been wringing about in the last year or so. And from this assessment, we can suggest the most probable future developments, the most imminent seeming to happen in the Palestinian fold.

The camps and their layers

We talked about this strategic outline of the Middle East many times in the last year. There are three main camps in the Middle East, all having similar patterns and desires to shape the future of the region, and all having similar struggles.

They are all based in the core partnership of a stronger, or senior partner and a weaker, or junior partner – possibly more-, with a big power behind them, an ideological theme, and a strong interest in the Palestinian matter, which is of vital interest in the Middle East. So in many ways, there are similar, though significantly different substances.

The Axis of Resistance

The first is generally referred to it by their own term, the “Axis of Resistance”. This is the oldest if the three, as it is built on the core Syrian-Iranian alliance slowing developing from 1980, and them evolving to something substantially bigger since the early 2000s after a decade of elapse. And being the oldest that went through the most changes. Syria, after decades of being the tip of the scale in several attempts to unite the Arab world under one agenda, has become a dominant power base by the late ‘70s, and had a still strong, yet fading theoretical basis with the Ba‘at ideology trying to unite the “Arab nation”, under one, secular national doctrine. After several successes since the late ‘50s, it was the dominant theme the Arab East in the ‘70s but received a fatal blow in 1979. After being the closest to the much desired Syrian-Iraqi union the coup of Ṣaddām Ḥussayn ended all hopes for this merger and practically sealed the fate of the Ba‘at, which from that point on have became a ideological theme with little true substance both in Iraq and Syria. Damascus never abandoned this ideology, and one listens to leading Syrian politicians, like presidential advisor Butayna Ša‘bān, can still hear such slogans. But this gradually gave space to a bigger project with the unfolding Syrian-Iranian alliance during the Iraq-Iran war.

As we touched it before, this was a very unlikely alliance to last between a still staunchly secular Arab-national Syria and the theocratic Persian Iran. The contradictions kept coming up in the ‘80s in the Lebanese civil war, as the two otherwise war allies kept supporting very different forces. With the setbacks of their individual agendas they learned to cooperate more, and the first time they managed to settle one dispute happened also in Lebanon. They both agreed to give prominence there to Ḥizb Allah, but with not abandoning the other Shii party, the Amal, which by now became the first two junior partners in the axis. Syria was the original dominant player in the axis, as it was practically the only state to give financial, military, and tactical support to Iran, mostly against Iraq, and giving it considerable diplomatic support in the Arab world. In time, however, especially after the end of the Iraq-Iran war, realities changed and Iran became the senior partner in the axis. This, however, was not as much dramatic until 2011, when the war on Syria started, in which Damascus had to rely heavily on the Iranian support at all levels.

Yet even before 2011 this alliance saw many developments much due to Syria’s role still not being truly inferior. In their alliance, Iran started to outdo Syria both financially and militarily, but it had no considerable big power support. Syria’s traditional strong connection with the Soviet Union, which was revived in the early 2000s with Russia helped to create bridges between Moscow and Tehran. In a very similar way, Syria’s than excellent ties with Turkey in the early 2000s – even before Erdoğan – managed to create good terms between Tehran and Ankara. This connection interestingly managed to survive the Syrian war, and now can be built upon for the benefit of Damascus primarily, but also for the advantage of the whole Axis of Resistance. Syria had another key asset for the camp, its excellent ties with the Palestinian factions, which until the Syrian war was the strongest by all regional states. Syria had traditional good ties with the PLO and ‘Arafāt. After these ties turned bitter, especially after Oslo, Damascus sheltered many of the Ḥamās’ leadership. The Palestinian cause plays a central element in Syria’s Ba‘at ideology, but was very adaptable to the Iranian ideology after the Islamic Revolution, and Syria meant access to the Iranians to the Palestinian fold.

The Axis of Resistance has a very solid, and still somewhat appealing ideological basis. Rejection of foreign, mostly Western, formal colonial presence in the Middle East, self-reliance in economy and military, and internal mediation in all disputes. Even the Islamic overtone of the doctrine shifted considerably in time, which in the beginning was the biggest contradiction. The Syrian state is much more receptive to these slogans by now, though for understandable interior reasons it still tones them down, while Iran, which after the Islamic Revolution envisioned the export of its own revolutionary doctrine seriously stepped back from it. One compares the slogans and aims of Ḥizb Allah in the ‘80 and now can clearly see this change. In short this is an alliance with a strong, though these days questionable economic-strategic doctrine, in which Iran is the senior, while Syria, Ḥizb Allah, Amal, and ever more Iraqi and Yemeni factions are the junior partners – on different levels. This has Russia behind it as the big power supporter, though not for the ideology, and especially via Syrian channels have strong influence in the Palestinian fold.

The Qatari-Turkish block

The other two camps in many ways and for a long time were walking in the same course but started to depart, and by 2013 completely departed to form their own camps. The camp which departed is what is known as the Turkish-Qatari block, which was formed on the alliance of these two states, but by now developed into something much more substantial. The Turkish-Qatari block, just like the Saudi-Emirati-Egyptian one before 2013 had excellent relations with the West. Turkey is still the second biggest NATO army, for long was a relatively good partner of the West in most Middle Eastern conflicts, and hosted the negotiations, which resulted in the Istanbul Cooperation Initiative in 2004, which in practical terms meant the extension of the NATO partnership to the Arab states of the Persian Gulf. Though Saudi Arabia since 1945 had a strategic partnership with the USA, which was even developed during the Iraq-Iran war and the Gulf war in 1991, but it was Turkey, which managed to create a more formal framework for the alliance with NATO. Which partnership officially still exists today. During the early stages of the fundamental changes caused by the so-called “Arab Spring” Turkey and its Gulf partners managed to gain serious inroads economically and politically in several Arab countries, including Egypt, Libya, and Tunisia, just to name a few.

Yet by 2013 serious cracks appeared in this formally one loose block for several reasons. The war in Syria reached a halting point, from which it couldn’t be pressed forward. The agenda could not progress and there were no more economic gains. Squabbling erupted, which was increased by the rivalry between Qatar and the Emirates. In the summer of 2013, a full swap of the Qatari leadership was enforced and the coup in Egypt squeezed all Turkish and Qatari interests out of Egypt, also cutting many projects in Northern Africa. That is how the dual partnership between Doha and Ankara, which existed even before, started to solidify. Qatar poured huge investments into the slowing Turkish economy, and by now it became the most important engine of it. In exchange, Turkey established military bases in Qatar, which saved it in 2017 when the Emirates and Saudi Arabia planned to instigate a coup or a military invasion as they did in Bahrain. In time this partnership not only managed to survive the American sanctions against Turkey and the Gulf blockade against Qatar, but even managed to make inroads in Sudan building a military base, Libya where Qatar is financing the Turkish military presence, and other parts of the Arab world.

Before 2013 this block had the US and the NATO behind them as the big power supporter. This support became much weaker, especially after Trump took office, with growing conflicts between Ankara and Washington in Syria and Iraq, but never really disappeared, as Turkey is still a NATO ally, in many significant matters it has an understanding with the Americans. Washington also never wanted to antagonize its ties with Doha, much due to the fact that the two biggest American airbases in the Middle East are Incirlik in Turkey and al-‘Udayd in Qatar. Qatar also gave significant diplomatic services to the US, as it hosted the first and only Ṭalebān diplomatic office, and hosted many rounds of negotiations between the Afghan group and the Americans to secure a viable American pullout. This has started under Obama and never diminished. On 20 February Agreement of Bringing Peace to Afghanistan was reached, which is a practical “peace deal” directly between the US and the Ṭalebān, signed in Doha. This all was hosted and mediated by Qatar, which is an important question, as with the pull out the Americans can end a costly engagement, and focus these forces on other, much more important matters. Therefore the big power partnership for this block was big enough to protect it from the Saudi-Emirati agenda, but by now it is insufficient to promote its own goals. Though in a side note, it has another nuclear power supporter, Pakistan on its side. Pakistan also lent troops to Qatar in 2017, and though it has excellent ties with Saudi Arabia, this is likely to change significantly, as recent protests and statements by Prime Minister ‘Umrān Hān leave no question that Islamabad cannot and will not go along the Emirati normalization with Israel.

The Qatari-Turkish block also has excellent inroads to the Palestinian fold, and for a very long time. Back in 2007 Qatari Emir at the time, Ḥamad ibn Halīfa started building good relations with Israeli Kadima leader and Foreign Minister at the time Tzipi Livni, and he secretly even visited Israel to endorse her bid for premiership. This tie, however, with the ascendence of Netanyahu slowly cooled off. The developing partnership with Turkey hitting different tones at that time halted Qatar’s progress on the road, in which now the Emirates succeeded, and as we can see by now Israel also had other options for partnership in the Gulf.

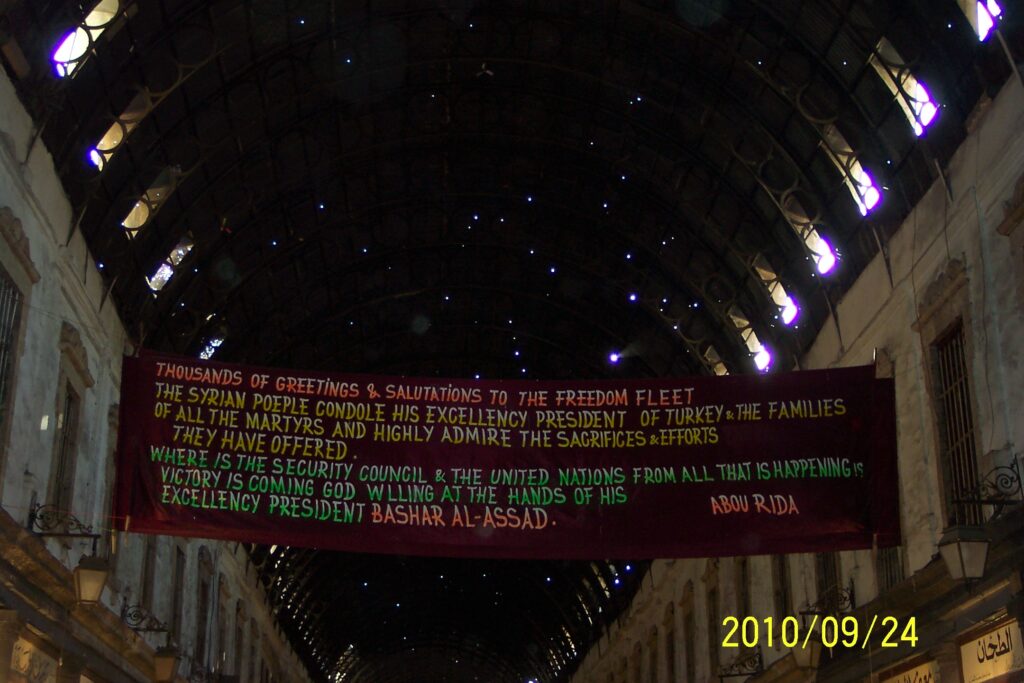

Turkey also had, and still have good economic and strategic ties with Israel. However, with the rise of Erdoğan the tone changed drastically and Turkey started its own bid to be the protector of the Palestinians. The infamous duel between Simon Peres and Erdoğan at Davos 2009 was only the first step, which was aggravated in the Mavi Marmara incident in May 2010 claiming the lives of 9 Turkish people on a ship attempted to bring aid to Gaza. At that time these actions had considerable Syrian support as well, and Erdoğan still holds on – through varying levels – to these rhetorics.

The war on Syria meant a considerable change in this matter, as many Palestinian groups like Ḥamas left Syria and found new shelter in Doha, and by 2013 posters in Palestine celebrated Qatari and Turkish leaders as saviors of the Palestinian cause. One sees the Qatari leadership knows that this block also has its Palestinian strongmen, apart from the now disillusioned Ḥamas strongmen, the former Syrian protege ‘Azmī Bišāra. He is a personal advisor of Qatari Emir Tamīm and aspires to play a strong role in Palestinian politics. His chances, however, were practically smashed recently, as we shall see.

The Turkish-Qatari block also has a very strong ideological theme, the support of the Muslim Brotherhood. Though Erdoğan himself uses the themes of Ottoman past and Turkic identity, these are more for the domestic fronts, and only applicable openly in certain matters, like holding on to Syrian and Iraqi territories, or lending support to certain Libyan factions. Beyond that, however, and with the great help of Qatar, this block utilizes the connections it has with the Muslim Brotherhood factions all over the Arab world. This provided inroads into Sudan before ‘Umar al-Bašīr was removed, into Libya, where the Turkish supported al-Wifāq government is of distinctly Brotherhood model and is there in Tunisia. Though seemingly this block has a much weaker, or less coherent economic solution model, this is not entirely the case. One of the conflicts between the UAE and Qatar is that for more than a decade now Doha aspires to be the economic hub of the Gulf, most especially to the Chinese Road and Belt initiative. This policy was highly successful, slowly causing an economic recession for Dubai, the former hub, which’s role was gradually taken over by Doha. Not a coincidence that Qatar was blockaded and one of the key goals of the blockade was to undermine Doha and the most import air traffic hub between Europe, the Middle East, and the Far East. And that prospect, inviting ever more Chinese investments and presence indicates that in the long run, this block hopes to find the economic and big power supporter in China it cannot hope unconditionally from the US, though this is still in a very early stage.

In short, this is a block in which Turkey is the senior partner, Qatar is a junior with many Muslim Brotherhood satellites. For now, it has America behind it as the big power supporter, though it has an eye on China to replace it. Has strong economic foundations, and with Qatari help and Turkish ambition have a serious role in the Palestinian fold. It just as much has the potential to be the leading block in the Middle East, and was on the winning side, at least until some two months ago.

Before we arrive at the last block, however, we have to point out something significant, which is very well exploited by the Saudi-Emirati-Egyptian block. Both mentioned camps have a strong non-Arab regional power in it as the senior partner, Turkey, and Iran respectively, which is not only projected as “foreign intrusion into Arab internal affairs”, but also works as an excuse to make Israel appear as an acceptable partner. After all, so far the argument goes, Israel is not any less “alien” to the Arab world, as Iran or Turkey.

The Emirati-Egyptian-Saudi Axis

This block was originally based on the partnership Saudi Arabia had with its much smaller Gulf neighbors, which in exchange looked up to it as a patron in sense. This Saudi role, however, was seriously questioned in the last decade by a number of factors. Riyadh, though went along with the restructuring of the Middle East in the so-called “Arab Spring”, failed to project a clear vision, or to truly lead. Thought it never really attempted this before. The utter reliance on the Americans also undermined this role. With King Fahd (1982-2005), King ‘Abd Allah (2005-2015), and King Salmān (2015-) a series of a weak monarch, the last children of the founding king ruled the kingdom, thus policy was determined not by one ruler, but by agreements between the feuding camps in the royal court.

At the same time with the slow decay of the Saudi leadership, the Emirates saw the rise of a new power base after the death of Sheikh Zāyid in 2004. His weak successor Halīfa was overshadowed by his strong half-brother Abū Zabī Crown Prince Muḥammad ibn Zāyid, who by now managed to form a very efficient ruling team. Though Muḥammad ibn Zāyid managed to form impressive personal alliances and was wise enough to stay away from risky adventures, unlike his Saudi counterpart, his probably biggest achievement was the recruitment of a Palestinian former strongman Muḥammad Daḥlān and luring Saudi Crown Prince Muḥammad ibn Salmān under his almost absolute influence. Undeniably Muḥammad ibn Zāyid himself is the nexus of the entire block. Having his power consolidated sufficiently enough by 2013, it was him, who promoted putting Qatar under pressure in the same summer, and with the help of Daḥlān and his associates gave immense help to Egyptian president as-Sīsī for his coup also the same year. Since then the Emirates completely replaced Turkey and Qatar in Egypt, the biggest, most populous, and militarily strongest Arab country, and poured huge sums into the Egyptian economy, which stabilized as-Sīsī in power. That reliance on Emirati funds above all else gave the strongest pillars in the block. The rise of Muḥammad ibn Salmān made Saudi Arabia more active than ever before in endeavors, like the war on Yemen, which was not for the benefit of the kingdom, but brought huge advantages to the UAE, and to Muḥammad ibn Zāyid personally. This block has a strong, though also a questionable economic model of strong Western partnership, and has the USA behind it as the strong power supporter. It also has an ideological basis, though by far this is the weakest out of the three camps. That is Islamic modernity, fighting radicalism, especially the Muslim Brotherhood, and building a strong partnership with the West. This is the most appealing for the West but was seriously hindered by the nature of the Saudi kingdom known for its religious zeal. This picture, however, was somewhat successfully changed with the PR campaigns of Muḥammad ibn Salmān, and all, even former blames of radicalism is now tagged on the Muslim Brotherhood headed by Qatar.

However, there were shortcomings for this group. First of all this block practically had no influence over the Palestinian matters. Thought for long Saudi Arabia claimed to be the biggest protector of the Palestinians, which now the Emirates claim for itself, this role was taken over by Turkey, Syria, and Iran. Though America was and is behind this camp, that support not only could not have been used against Qatar, as Washington does not wish to antagonize its relations with any Gulf state, but even against Iran, or to solidify gains in Yemen, as we could see in the event of last summer. This was a protection, but not a supporting force. Which was even made worse by the self-loaded comments of Trump, saying that he will “milk” the Gulf states. This prompted the idea that it is time to bring in another, a possible second senior partner into the camp. And that is exactly what happened.

Where the Abraham Accords changed the game

Looking back to the events of the last two to five years it is clear to see that this last camp was the weakest and was in a growing crisis. Muḥammad ibn Salmān could not put an end to the coup attempts, and newer and newer rounds of purges followed. Which is still going on? The Saudi-Emirate war effort in Yemen failed to reach a decisive end and was even losing ground. The Yemeni government they supported practically fell apart, which prompted the Emirate to salvage most of the gains by carving out a separate state in the south for itself, thus giving up the dream to bring Yemen under total control. The coup in Sudan was successful, but the new government is still weak and very reluctant to support the block in a number of key issues. The tensions with Iran last summer showed that Washington is not willing to plunge itself to a costly and probably devastating war with Iran, and at the end, the Emirates had to settle with Tehran. The Emirati bid against Qatar was not yielding any benefit, and the blockade started to turn against it. And finally, Egypt after all threats could not use its force in Libya to protect its interest, nor to handle Ethiopia alone.

Now suddenly all that changed to the contrary and the Egyptian-Saudi-Emirati block became the strongest, with inviting a new senior partner into the club. That is Israel. We already saw that Israel started to work together with the UAE in Yemen, which will help to solidify its grip on the south and not let Abū Zabī end this adventure without benefit. The presence of Israel in the Emirates will make it invulnerable, at least that is what they believe it, and surely Israel will be more willing to take steps against Iran. That is regardless of all Emirati claims that the alliance is not against Tehran very clear. It is also hoped that with Israeli partnership the declining Emirati economy can be pumped up once again, especially in fields of IT and biotechnology.

It is clear that Abū Zabī made an impression, as allegedly Trump tasked Kushner to “solve” the conflict with Qatar, which means that Qatar will be forced to the deal with Israel. That would put Qatar under Emirati-Israeli influence, since there can be little doubt about the nature of the “peace solution”, by which Qatar and an independent actor would be cripples, thus the Turkish-Qatari block smashed.

The biggest gain, however, which we suggested two weeks ago, was only confirmed recently. Muḥammad Daḥlān, who was once the security chief of the PLO and trusted man of ‘Arafāt, until he was replaced and later exiled by now Palestinian president ‘Abbās to be one of the most important assets of the UAE leadership is about to be endorsed by Washington to be the new Palestinian president. If that happens, he will likely sign the Deal of the Century, the final “peace accords” with Israel, and will be the first globally acknowledged Palestinian president of the formal state. With this, the Emirati-Egyptian-Saudi camp, which with the accords confirmed its sovereignty over Bahrain, will gain Palestine as a formal partner. Which will be led by a man of the UAE, and a strong member of the Egyptian power structure. Thus Abū Zabī will be able to claim that it did what no other attempts could do, bringing an end to the Palestinian matter, bringing peace and security, and claim moral prominence over Palestine. This would cripple a key ideological pillar in both rival camps’ narrative.

Furthermore, there is already a long feud between Daḥlān and Turkey, as Ankara claims that Daḥlān stood behind the failed coup attempt in 2016. Which is not only very likely but with the possible crippling of the Qatari-Turkish alliance will likely to continue. The prospects are therefore huge.

The responses

It is very clear that the other blocks have to react to this development, not the least, because to some extent is this both aimed against Iran and Turkey. The last meeting between Iran and Turkey and the statements by Iranian president Rōḥānī clearly indicate that they have to react together to the new challenges ahead.

This, however, has many contradictions that have to be settled first. Matters, like conflicting agendas, are Syria and Iraq, relations with Russia, economic partnership. And here haven’t even spoken about those states, which were not part of any camp, but now have to choose. As even in the Gulf, not everyone is happy with the developments.

All that, however, will be discussed next week.