Since Biden took office the biggest questions about his Middle East politics revolve around Iran. The top of the list being the question of whether Washington returns to the JCPOA, the nuclear deal, and if so, under what circumstances. All other matters came secondary, yet had much to do with this primarily matter. So much so, as it would seems that all other considerations are measured in comparison to the Iran case.

We dealt with the first such example last week, Yemen. Clearly, Yemen is not a priority for Biden, nor for the U.S. in general, but in the context of its behavior towards Saudi Arabia, the Gulf in general, and Iran it is significant. Because it is a valuable bargaining chip both ways. So far the Biden administration was willing to make remarkable gestures to appease the Anṣār Allah Movement-led Sana’a government, like taking them off the terrorist list or stopping support for some of the Saudi operations in the country. All that serves the purpose to prevent the fall of Ma’rib, the last major Saudi possession in the north of Yemen. This seems to be inevitable at this point, yet the negotiations are not over. And as we saw, both Tehran and Washington are raising the stakes.

Since then Washington offered to return to the JCPOA – under certain conditions – and as a token of goodwill on 19 February Biden withdrew the request made by Trump for certain U.S. sanctions. So it would appear that Washington is hopeful for some sort of arrangement and there are promising tokens of goodwill. All looks to proceed straight in a more conciliatory way.

But there is two other major fields where the interests of Tehran and Washington are deeply contradicting. Iraq and Syria. In both of these cases, the problem is not only the antagonism between the American and the Iranian allies, both supporting different sides in the local conflicts. All considerations are overshadowed by their respective regional allies also interested in conflicts, and they are all very actively affect the equation.

Iraq is a complex question, which should deserve our attention separately soon enough. Yet this week we shall focus on Syria because much is going on and not everything is moved around by Washington or Tehran. Which might give space to some sort of agreement. Or is it?

The actions of Biden are less than clear about Syria since he took office. Quite the opposite actually. There have been illegal American bases evacuated and there have been words about a possible full withdrawal. But on the other hand, there have been some new bases fetched up, the separatists Qasad militia is remarkably active, there have been suspicious activities by Dā‘iš, and the most pressing matter, the American sanctions are untouched. These are, however, not the only odd events around Syria recently.

To go or not to go

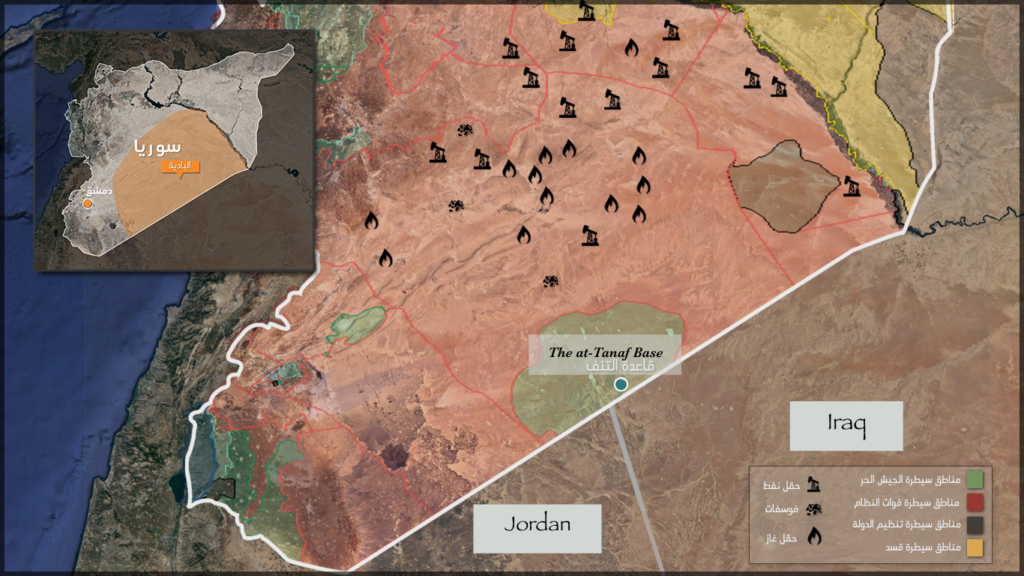

One of the main questions about Biden conceding Syria was whether he would end this American engagement and pull out, or continue his team’s former policy on a more radical step and move for invasion. Neither is easy. An invasion while Russia is present and resistance is expected from it is extremely risky. The pullout was promised and seriously tried by Trump and failed on the manipulation of the military-intelligence establishment. In theory, Washington could continue what it was doing for the last 2-4 years sitting on the oil, supporting the separatist elements enforcing more sanctions, and wait for the Syrian state to break. And this might very much happen, but in the context of the general policy rearrangement and negotiations with Iran, some form of change will probably happen, even if only symbolic.

One of the first notable acts of Biden was announced in early February that the American troops no longer guard the oil wells in Syria. Which has the tone that the American is getting ready to pull out, yet in reality, the statement only said that the duty of the occupying forces is to fight Dā‘iš not to guard the oil. This does not mean the troops left the oil fields, only that much of the guard duties were handed over to local radicals.

It was further promising that around the same time the matter of pullout was openly raised by Washington. And it was soon followed by the first abandoned military base on 12 February, which was an important service hub close to the Iraqi border. Since that day yet another base was evacuated, which would support the idea of the slow and gradual pullout.

Yet the picture is not that clear, as the American forces since Biden took over also pulled in massive supplies and started building two new large bases around aš-Šaddādī south of al-Ḥasaka. What is even more troubling is that during the last month or so the otherwise uneasy relations between the American-backed – allegedly – Kurdish separatist Qasad militia, the Syrian state, and the local tribes completely broke down. The Qasad, which lately got bolden by the Americans its on ways on the local population, closing schools, enforcing curriculum, appropriating properties, and acting as a local authority, which caused huge tensions. Since the summer the tribes are in an act of revolt. The attacks against the Americans are getting more frequent, but by now the clashes with Qasad became a daily phenomenon. While the skirmish against them are frequent, their answers by random raids and arrests – sometimes even against Syrian soldiers – are many times directly supported by the American troops.

The other troubling sign which led many to believe that Washington might be planning an invasion is that since mid-January the Dā‘iš became extremely active. Not just in Syria, but also in Iraq. Most of the activities happened deep in the Syrian desert, while the infiltrating groups usually come from the south crossing over from the Jordanian border. Strangely that is the very area, where the American illegal base is present at at-Tanaf. And that is the very same place where the Americans transported 60 Dā‘iš terrorists in early January from Eastern Syria, while ten days later they moved there 100 new terrorists from Iraq. In this context, Washington’s claim that the U.S. troops are in Syria to fight Dā‘iš and not to guard the oil anymore is much less promising. Because it suggests that they are ready to be more active once again at a time when the terrorist activity – strangely solely around the American and Turkish bases – is rising.

It is probably not a coincidence that seeing the growing violence with Qasad Russia took huge efforts to hammer out a deal and reach a ceasefire. So far the Russian troops did not intervene directly, but this was also suggested. The real problem, however, is not Qasad, but the Americans behind them. Was it not for them the Qasad would not dare to openly challenge the Syrian state institutions? Also on 12 February, it was announced that Russia would develop its airbase in Syria to receive nuclear bombers, which will soon station there. Meaning that soon enough Russia will – or might – deploy nuclear bombs in Syria. Even though Moscow also announced many times that the number of Russian troops is to be reduced and a pullout should happen. That is a very serious message that Russia is not about to allow any direct aggression against the Syrian state, but also that it trusts its Syrian ally.

From Damascus’ point of view, these Russian steps are very commendable. But recently a number of matters harmed this relation.

A troubled friendship?

As the new rounds of Russian-Iranian-Turkish direct talks over Syria started on 15 February 2021 – less a month after the last round of Geneva talks – Russia’s position became questionable by many Syrians. It is on its own very curious why Russia is keen to hold good relations with Turkey, while Ankara clearly plays a very destructive role in the conflict. While the negotiations in Sochi did not specifically bring anything groundbreaking, not much later on 20 February a Russian-Turkish agricultural deal was reported, by which grain from the Syria territories occupied by the Turkish army and the Turkish-backed mercenaries was to be transported to Aleppo under the Syria government control. This officially aims to ease the food shortages in Syria, but surely has major benefits for Turkey as well.

However, recently even much more troubling suggestions arose about Russia’s role in Syria. There have been reports about a plan to replace Syrian President Baššār al-Asad before this year’s expected presidential election with a military council. Allegedly there is a large number of Syrian officers willing to participate in this project and would be led by Manāf Ṭalās, son of late Muṣṭafā Ṭalās, who was a legendary Syrian Sunni general, Defense Minister, strongmen and a key ally of late President Ḥāfiẓ al-Asad. Manāf Ṭalās defected from the Syrian army during the current crisis and left the country, while he was allegedly very close to the foreign-sponsored armed groups. Even more interesting that according to the hypothesis this council would not only include the Qasad militia, a clearly American-backed separatist entity, which is a major source of trouble for Damascus now, but all “opposition groups” as well, and even gained tacit Russian approval.

This sounds very wild and illogical, practically crossing over all the previous Russian attempts to preserve the functioning Syria state, and would count as a betrayal. Considering that all these reports can be traced back to Saudi, or Saudi sponsored sources this could easily be disregarded as malicious propaganda to sow distrust. And on the sidelines of the Sochi talks, President Putin’s personal envoy to Syria Aleksandr Lavrentyev denied such accusations. Reportedly he said that all talks about Russia’s involvement in such a military council are “deliberate misinformation aimed at undermining the talks and the political process of Syria.” This seems convincing, especially that during the years of the war on Syria numerous times similar allegations were raised, all to be proved false later on. However, it was not only Saudi affiliated outlets, which openly and seriously discussed this idea. On 11 February RT Arabic aired a discussion on the topic with full seriousness.

And even more, while all the phrases and the context resembled the terminology of the so-called “opposition”, the guests were the editor of the Le Monde Arabic and spokesman of the separatist Qasad militia. Yet there was no guest at all to express the opinion of the Syrian state, which is more than curious from a “friendly” outlet.

This was not a lone incident. On 16 February about the talks in Sochi a different program of the same channel hosted two guests for discussion. A member of the Syrian Social-National Party – an internal opposition party – and the head of the “Opposition Delegation”. The latter was Aḥmad Ṭu‘ma, a notorious member of the Turkish-sponsored armed gangs, who once posed as “interim President of Syria”. Once again, there was no guest on the Syrian government’s behalf.

So when Lavrentyev says that talks on a Syrian military council are “deliberate misinformation” this might be true, but RT, Russia’s biggest Arabic language outlet itself was involved in it. And not in a satirical way.

Something, however, changed after Sochi. Right after the very same Lavrentyev warned Tel Aviv to stop its airstrikes against Syria, otherwise “the patience of Damascus might run out”. This is a clear message that Russia is annoyed by the constant Israeli bombardment and the Syrian complaints. So if Israel does not change, Russia will not block Syria from hitting back. That of course most probably not mean direct Russian assistance, but Moscow might give a green light to the Syrians, or even the Iranians to hit back severely. Which at this stage would be very harmful to Netanyahu’s reputation.

While this was going on another strange event happened, which further stressed that Russia is pressuring Israel now for Syria’s benefit. On 17 February an Israeli “lady” – about whom there is very little information ever since – crossed into the Syrian province of al-Qunayṭra, where she was detained by the Syrian authorities. A day later a deal was arranged with Russian mediation, by which this “lady” was exchanged to two Syrian prisoners held in Israel. According to Israeli sources, the lady was a strange nature who miraculously crossed the border by accident, while Arab sources claim her to be an Israeli intelligence operative. Either way, the speed and the effort Tel Aviv took to return an allegedly “ordinary citizen” ranger suggest that big things were happening behind the scenes and this was no random incident.

A few days later it was alleged that the deal also included that Israel buys two million Sputnik V vaccines for Syria as an act of goodwill and a humanitarian gesture. This was denied by Damascus and it is probably exaggerated, the very notion that Russia would make Israel pay for the vaccines it donates to Syria is remarkable. And suggest that Syria did not just stumble upon a weird Israeli citizen.

As it can be seen Russia’s role in Syria changed a lot in the last few years and there is a growing frustration. While in 2015 Russians were welcomed as saviors, the Russian presence by now is not considered so favorably. Much more is expected of Moscow about the Turkish and the American presence, and also to help ease the sanctions on Syria. On the other hand, however, the support Moscow gives internationally, diplomatically, and now against the Corona pandemic is invaluable. These circumstances make the Syrian-Russia relations troubled these days. And that gives space to other players, Iran, but also the Americans to exploit this tension for the benefit of their own agendas.

Choices and elections

The biggest matters of the Syrian question are the same for the last three years with very little change. The war itself is over, the Syrian state overcame the attack, which was launched against it, not the least by the administration in which Biden was the Vice President. But there are large parts of the country still under illegal American and Turkish occupation. While that can – at least theoretically – be ended any time if there is a will, both of these states built up a massive mercenary force on the ground, which has to be dealt with. And while there are no easy answers to this problem, nor Ankara, nor Washington is ready to relinquish these tools.

The other major problem is the catastrophic state of the Syrian economy. The sanctions are just one side of the problem. The Corona pandemic and the precarious conditions in both Lebanon and Iraq practically sealed off Syria from foreign trade. There are potential investors, even supporting forces for the reconstruction, but these are hard to capitalize upon, as Russia is advancing its own economic benefit and blocks most of the rivals.

Internationally the Syria case is getting secondary to conflicts, like Libya or Yemen, and that is why the works of the “Constitutional Council” go so terribly slow. Nonetheless, the negotiation processes are going on both in Astana, Geneva and the U.N. There seems to be little progress now, but all can feel that the biggest obstacle is that the outer powers still haven’t agreed on how to end this conflict with minimal losses in their interests.

This might come to an end soon, especially with the ascendence of a new American administration. And if so the presidential election sometime in mid-2021 will be the perfect ground to start the process, which finally closes the Syrian war.