No doubt the Abraham Accords between Israel, the UAE, and Bahrain, which has unofficially but very practically opened the door for the normalization between the Jewish state and a number of Arab states with the Gulf in the first line created shockwaves, which still moves political deliberations all around the region. As we saw that is not because these relations are anything new. Quite the contrary. The political alliance between a number of Gulf states and Israel, directly to keep Iran at bay, but also to serve other ambitions of political control at home and in the region by some leaders is a very old story. For some, it was self-evident, while for other a clear sign of conspiracy theory, but nonetheless, it was a well-circulated political theme for decades. The difference is that until now all these ties, though they were very real and contributed largely to the general deterioration of the Arab world and many common Arab platforms, like the Arab League, were denied and kept unofficial. By Abraham Accords, all came to the surface.

The shock, the realization of this so far inconceivable trajectory is enormous. Many, who cannot deny the reality anymore, namely that a great part of the Arab world simply stepped over the Palestinian matter, thus the biggest obstacle of the alliance between them and Israel being lifted, shifted their denial to the theme that such relations, alliance might from, but there cannot be alliances between the people. Forgetting, or knowingly disregarding the fact that politics is largely a game of the leaders, not the people. And for proof, they point to the example of Egypt and Jordan, which two states never really formed any clear, or official bond, or any common strategic front with the Jewish state in spite of their formal recognition for it and the diplomatic ties.

Here the difference is, and that is constantly reminded of by Netanyahu and a number of Israeli leading politicians that the circumstances are fundamentally different. Those agreements were made for land, political assurances, and by pressures from outside. Unlike now, as this time the main trigger factors are the political and economic ambitions of one state, the UAE, and its leadership. The agreement is only a tool for much bigger plans, not an aim anymore, like a decade ago.

Regardless of the denial by many and the slowly dissipating illusion that popular refusal will be a major obstacle in this path came, it is undeniable by now that Israel’s official appearance and probable further gains reshuffled the calculations all over the region, and for every major state. Which raised the question, who lost the most with the deal?

The obvious answer to this question seems to be Palestine, but in fact, there is little change to be expected, as the Palestinian matter for long has been result of a clear equation. The Israeli willingness to compromise, and the outer – Arab, Iranian, or Turkish – support willing and able to change the situation. And in this regard, Abraham Accords brought almost nothing new. Others might also point to Syria, Lebanon, Algeria, Tunisia, or other states still staunchly refusing the normalization. Yet they are hardly calculated within this major realignment, as their reaction was anticipated.

In this light, it is interesting to see that more and more assessments both in the West and in the Arab world Egypt as the biggest to lose from this development. Which is curious, not only by the fact that the Egyptian policy and the state-run media did its best to support and advertise the agreement but also because Egyptian President as-Sīsī is a close ally and a dear protégée of the Emirati leadership. This all comes in a time when as-Sīsī faces huge problems at home and the biggest protests since he quelled the rebellion right after he overtakes of the country. And his regional prospects, after a fruitless showdown with Turkey in Libya, and equally futile power politics against Ethiopia are not any better.

Therefore it worths to assess how much the Abraham Accords changed the possibilities of Egypt, and as-Sīsī personally, after more than seven years for him on power, as his fortune seems to take a serious downturn. Given the weight and significance of Egypt to the whole Arab world it is easy to see that a cataclysm in Egypt might create news shockwaves for the whole region. Bigger than the infamous “Arab Spring”.

Doubtful economy

When as-Sīsī took power in the summer of 2013 the Egyptian economy was already in very dire circumstances for years. The liberal economic policies of the Mubārak era, especially in its last decade certainty boosted certain sectors, but in large had such social and overall economic implications – combined with corruption and inefficiency – that it greatly contributed to the meltdown of the Mubārak government. Political turmoil and the controversial rule of the Muslim Brotherhood under Mursī never managed to help the situation – it hardly had any time, nor a chance for it – and the regional uncertainties largely crippled the tourism, a major source revenue, and work opportunity. That is the situation as-Sīsī had to deal with upon his arrival to power. He managed to secure the economic privileges of the army’s officers’ corps, which were threatened under Mursī, and that secured his grip on power to this very day. Confrontation with Qatar and Turkey after their harmful presence in the Egyptian economy was eliminated meant an obstacle, but the lost investments were compensated by equally substantial Emirati and Saudi support. By 2016 these were met with the gradual return of Western investors and loans from the World Bank and the EU.

Yet the challenge remained that investments had to be channeled to boost the economy and also to create work opportunities. Thus to curb unemployment, which is not only an economic and social hazard but even more a political one in a country with huge urban poverty and the still influential Muslim Brotherhood’s ability to agitate the streets. As-Sīsī’s response was a series of giga projects, from urban development and finally building the new Grand Egyptian Museum – the biggest in the region costing some $791 million – to building a new administrative capital. Most of these projects served Emirati business interests and had the UAE’s investments behind them, but all served in one way or another the internal political interests of as-Sīsī’s government. Many, however, like the massive $58 billion projects of the new capital started to suffer in recent years after partial completion, as investors started to pull out. The gemstone of all was undoubtedly the New Suez Canal project, which with its roughly $4.2 billion was far from being the biggest, but was a dream since as-Sādāt and had a huge economic potential. Even more importantly that was directly linked to as-Sīsī, who elevated the endeavor to a national level, and took great pride in it when it was completed.

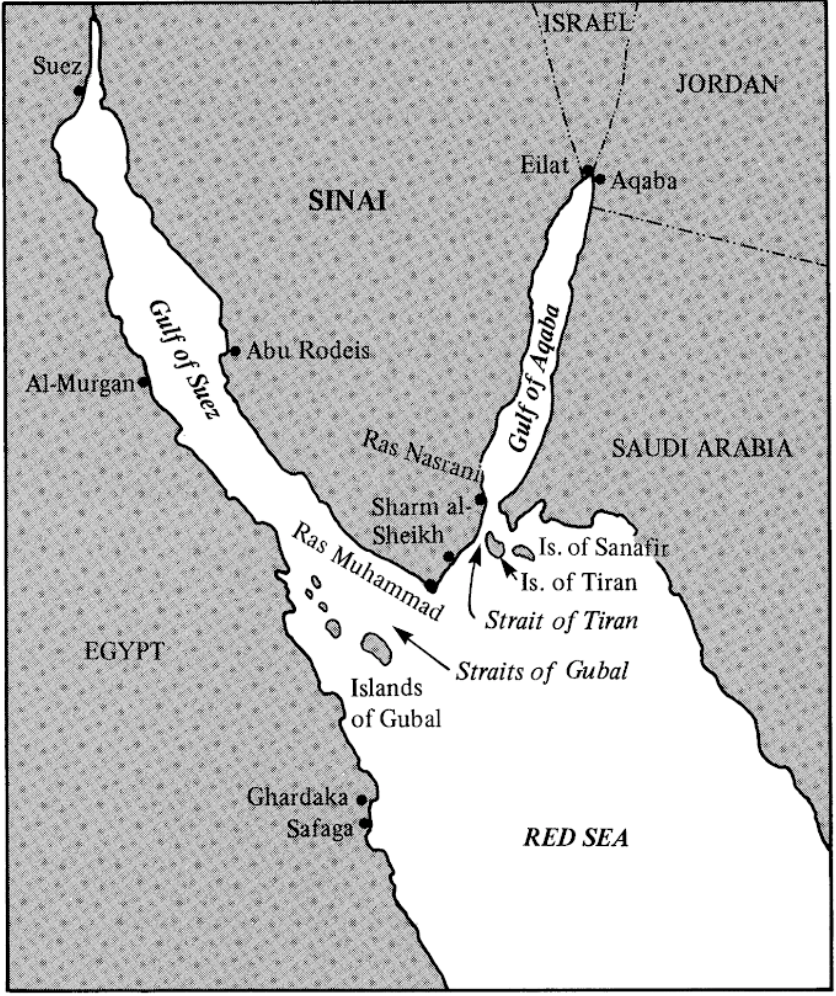

Recent developments, however, turned many of these projects bitter. Investors started to pull out, Saudi and Emirati support – mostly for their own inner troubles – started to vain, and then the Corona crisis hit the country. With the huge fall in long-distance trade the project, which suffered the most was the New Suez Canal, which started to lose its economic rationale. And that is exactly where the Abraham Accords might prove fatal for as-Sīsī. Recent reports indicate that the New Suez Canal might become obsolete much sooner than anticipated, as the Emirates started to sign economic treaties with Israel delivering Emirati oil directly from Dubai and Fuğayra to the port of Eilat in the Red Sea.

From there transports will reach the ports of Ashkelon and Haifa, connecting the Gulf to the European markets via Israel much cheaper than via Egypt. The rationale here is that soon there will be a direct pipeline connection between Israel and the EU, without additional transport costs. As early as 2013 the EU approved the construction of an undersea gas pipeline from Israel via Cyprus to Greece, and from there to Italy. The three countries in the presence of State Secretary Mike Pompeo signed the so-called “EastMed gas pipeline” agreement on 20 March 2019, and Israel has recently approved the building of this $6.9 billion project. A project expected to be completed by 2025 the latest. Even more menacing for Egypt, this trajectory indicates that if the UAE manages to secure Saudi support, the Gulf oil grid can be connected in the close future to the Israeli, and from there to the European one. Not even touching the oil transfer, it seems clearly indicated that by the normalization the massive transport trade, which was for decades ruled by Dubai, until Doha became a major rival, might soon be rerouted to Eilat.

One infamous indication of this gradual shift is the “King Salmān Bridge project” connecting Saudi Arabia and Egypt at the Strait of Tiran. That was to be fully financed by Riyadh and heavy legal battle was fought about the rights for the islands in the Strait, but in recent years the project simply disappeared from the news and stayed unfinished. Many ideas, like this one, are in early, or partially constructed phases, but funds ran out, and those which are finished are losing importance. The problem is that by now both the Emirates and Saudi Arabia lost interest in developing such major Egyptian plans, as the Israeli cooperation has much bigger prospects.

And as mentioned by many analysts, especially those Egyptians in exile, the country took a very drastic downturn in recent years. While national debt was successfully cut back from the soaring 108% in 2017 to roughly 90% by 2019, the non-oil sector economy rapidly shrinks. Official unemployment reaches 10%, much worse in urban areas, and the reality is probably much higher, while the inflation keeps fluctuating regardless of the major currency devaluation in 2016. Most shocking of all is the extreme poverty rate, which more than a year ago reached 32,5% with no sign of stopping. In light of these indicators the Giga projects, especially after reaching a halt, seem to a questionable policy, which understandably causes large scale frustration.

Growing regional isolation

These contradictions, the fear that in time Riyadh and Abū Zabī would simply stop financing these projects were present before, but until now Egypt had the leverage that it apart from its economic magnitude it has the military weight the Gulf needs both as a security guarantee and as means for its political agenda. However, with Israel appearing in the scene Egypt almost instantly lost this card. And that is not the only one.

For a long Egypt could claim and rationalize its links with Israel as being the main nexus between the Arab world and Israel, thus the most important power broker in the Palestinian fold. The only major force, which can mediate between Israel, Palestine, and the Arab sides involved in the matter. This mediation has also become obsolete. Not only because the direct link has been established since the UAE is not interested in solving the Palestinian matter and Bahrain greatly lacks the capabilities for that, but because, as indicated before, Abū Zabī already has a winning card in the matter with future Palestinian president candidate Daḥlān. The situation greatly changed in the last seven years, and very badly for as-Sīsī. In short, while in 2013 and even before the Saudi-Emirati duo needed Egypt, it does not need it anymore, while Cairo is still largely dependent on these relations.

And while the UAE and the whole camp around it greatly improves, or even solve most of its pending regional concerns, Egypt is stuck with its involvement in Libya, with its vital struggle with Ethiopia over the Nile, and with its still ongoing struggle against Turkey and Qatar. And it can achieve very little progress.

One possible way out was the resurrection of an old constellation, the Iraqi-Jordanian-Egyptian cooperation. For that, on 25 August the three heads of state met in Amman and held intensive talks about economic partnership. Indeed these states have much to offer for each other and have no disputes. Politically as well, such a new axis could be ideal, as Iraqi President al-Kāẓimī is desperately trying to pull farther from Iran and Jordan as well as in a deep crisis without supporters. Realistically, however, at this stage, such a new axis seems to be a very weak possibly, as Iraq is way too tied to Iran, while Jordan can hardly distance itself from the Saudi-Emirati line of normalization.

A fatal new project?

In September, regardless of all setback but well in line with the previously started trend, the Egyptian government started a new economic-social campaign. Ironically, while many of as-Sīsī’s decisions were controversial and he did indeed seemed to be a pawn in his Gulf supporters hand, the decision, which brought him so far closest to downfall was the one showing the most statehood characteristics.

For long, and this is far from being peculiar to Egypt, the country suffered from haphazard appearing slum districts in many major cities. Complete neighborhoods were built under dubious circumstances, many times without any licenses or proper engineering, or already existing neighborhoods became overgrown by randomly built huge residential buildings. Which in recent times caused several disasters randomly collapsing. That exists in many parts of the Arab world, but Egypt being by far the biggest, its slum problems are also bigger by a magnitude.

Partially to tackle the safety hazard, but even more, to create order in this notoriously chaotic urban jungle as-Sīsī launched a massive campaign to demolish these. Whole districts, which had no permits were pulled down with the promise that in time new, but organized quarters will be created.

While this sounds to be a reasonable enough plan, especially if someone has been to Cairo, Asyūṭ, or Luxor recently, the controversies are numerous. Demolitions were executed with full vigilance, which was beneficial, but with little to no regard to the residents, who many times were simply put to the streets. Also, it was clear to see that these policies are mostly implemented in areas, where planes are ready for new, organized, but largely unaffordable quarters. With such much massive poverty in urban areas, this was less noticed but the tension was boiling and it reached a threshold with the destruction of the first slum mosques. What’s worse than this has become a trend and in reaction to the massive protest and criticism as-Sīsī responded by saying: “Mosque cannot build on forbidden land! Only in land allocated to it, and by agreement of the government!” Not surprising that protests broke out, as haphazardly built mosques were torn down in a number of cities. These were the biggest since 2014, which were mild in the north, but very menacing in the south, especially for the slogans much too familiar from 2014, when as-Sīsī had squash a real rebellion in Cairo.

This goes largely unnoticed in the West now, as as-Sīsī is still regarded as a stabile character in a highly volatile region, but has already caused shockwaves in the Arab world. And this is only further exacerbated by the huge number of Egyptian tv anchors – mostly in exile in Turkey, or Qatar – who put oil in the fire with their vitriolic – and not unfounded – criticism over the President.

As long as as-Sīsī has the army and the officer corps firmly behind him that should not worry him, as the state authorities have way enough means to handle the situation. Yet with the current state of the economy and possibly even worse coming, these are very troubling prospects.

Buying grace?

For long as-Sīsī had a talent for causing controversies with his urban reconstruction campaign, while at the same time makes huge army purchase deals. Yet when Macron visited Cairo in 2017 winning major investment projects for French companies in the press conference the Egyptian President got carried away in reaction to criticism and managed to say this: “Don’t ask me about the right of a good education! We don’t have a good education! Don’t ask me about the right to good healthcare! We don’t have good healthcare in Egypt.” The latest of these is the scandals that as-Sīsī was financing Trump’s campaign in 2016 through an Egyptian bank with $10 million, and there is a big likelihood that he would do the same now. So why are the huge spending on the army, if that cannot be used? Why are such political favors, if the overall prospect is bad? Why supporting the normalization, when it has potentially destructive implications?

While most of these steps have very bad results on Egypt, the large sums by which as-Sīsī supports the French, Russian, or German industry helps him stay in favor of the big powers. Help him stay in office. That is why Trump is such valued ally since regardless of the criticism for some Russian arms deal, Trump seriously turned the criticism Obama was so famous for against Egypt. And in the meantime help to push his agenda against Turkey with Russian, or now French help.

While that might help him even in the middle run to stay in office, this policy has increasingly terrifying prospects for the economy. And if that does not improve social implosion might be unavoidable.

While the state-run media celebrates the policies of the Emirati ally, as-Sīsī hasn’t openly commented on the Abraham Accords, and rightly so. Because he might indeed be one of the biggest losers of it.