This week the Gulf managed to gain the attention of the headlines in a way more suitable to their projected image of being an exotic partner of the West as one of the great royal households, though in a negative way. The Emirates, which still managed to hide behind Saudi Arabia in the Western evaluations in light of the recently flaring up tension between the Gulf Arab states and Iran, this week got the attention of the celebrity news, as wife of Dubai’s ruler, Hayā bint al-Ḥussayn announced in London that she leaves his husband and asks political asylum in Germany. Many who resent the UAE’s recent negative role in most of the local disputes all over the Arab world now can’t help, but to scorn Dubai’s monarch, Muḥammad ibn Rāšid Āl Maktūm as if faith has its revenge on the Emirates. More so that it was not the only recent negative news about the country, as on 2 July the heir of another emirate in the UAE, Hālid al-Qāsimī of aš-Šāriqa deceased, and strangely, also in the UK. The “defection” of Princess Hayā naturally brings attention now, as Germany refused to extradite her, or her two children to any country, which is a great shame for Dubai. But some details show that this scandal is caused by much more than a simple family dispute and has great connections to our last week’s topic.

Price Hayā is from the Hāšimī royal household of Jordan, half brother of the Jordanian king ‘Abd Allah and by numerous sources she had much to do with the rumored coup attempt. This development reveals deep divisions – long known for experts – within the Emirates and points to great realigning attempts now. Since less covered, but the Emirates recently took a very surprising step. UAE Foreign Minister ‘Abd Allah ibn Zāyid in a bilateral conference in Moscow 27 June 2019 refrained from accusing Iran for the recent attacks on oil tankers in the Gulf. This left many to wonder what caused Abū Zabī to suddenly show prudence and not to follow the previous line to cause tension, even if this came in Moscow. Even more puzzling that after much effort news came out that the Emirates has started to pull out from Yemen as well both in an attempt to reenforce is security, but also to free some energy to bigger matters.

Why all these seemingly unrelated news now, and how do they add up? What has the scandalous defection of the princess has to do with this, and what does all have to do with our topic from last week? The picture is more complex as many would think and there are many points seem to be hidden now from the Western reader from this exotic, yet favorably imagined country now.

The royal refugee

There are basically three, seemingly less related issues now in hand which came together and now puts the UAE to crossroads how to continue from here. These are the story of Princess Hayā, the struggle between the individual emirates within the state, most imperative between Abū Zabī and Dubai, and the effects of all these of the regional politics, which naturally culminates in the attempt we know now as “deal of the century”. And to see the matters right we have to see these factors one by one.

Princess Hayā bint Ḥussayn al-Hāšimī is from the Jordanian royal family, eldest child of late King Ḥussayn from her third wife, ‘Aliyā’ Ṭūqān, from whom Hayā also has younger brother, ‘Alī.

Born in 1974 she studied in the UK and reportedly an enthusiastic equestrian with a reputable history of U.N. charitable and sport services. In 2004 she married to Muḥammad ibn Rāšid Āl Maktūm, the current monarch of Dubai as his second wife. The marriage was arranged as an attempt to boost cooperation between royal Arab households. Thought the two have two minor children the marriage was never really happy, partially for her husband’s first, main wife and other five others. Apart from their differences few problems emerged between the two, at least publicly, as the emir was a great supporter of his wife’s equestrian hobbies and secured her a lavish lifestyle. Rumors have it that he only barred her to meddle in politics in any ways and specifically banned her to have any contacts with the ruling elite in Abū Zabī. Now within this context of cold, but balanced relation came the news that on 30 June that Princess Hayā left the UAE with her two children, with some £31 million with the help of an alleged German diplomat, though unconfirmed sources claim that she was wasn’t seen in public since mid May.

Many things, especially the timing still remains mysterious in the case, mostly that she claimed asylum in Germany, though she is in hiding in London. The first two obvious question is that if she was afraid for her life – as she now claims -, why did she not move to Jordan, or why did she ask asylum in Germany instead of the UK, considering she has excellent connections there. The later is easier to answer as London, being the former colonizing power and still greatest supporter for both Jordan and the Emirates, would unlikely have given asylum, not to antagonize its relations with its former colonies. But if Germany gave that to her, she could easily stay in any EU countries, as none of them would have the legal basis to extradite her either to Dubai or to the Hāšimī kingdom. The other question, why she didn’t go to Jordan is much more complex, though it is very telling that this question is not even suggested in the Western press, now very eager to follow the case.

Strangely enough after a few days the Western press came out with yet about Cinderella type of answer as the case has much to do with another “defection” from the Dubai royal household. According to this version Princess Hayā made her decision after learning disturbing facts about one of the emir’s daughters, Laṭīfa, who last year made another sensational escape with the help of a – former? – French diplomat. Laṭīfa and her companion were intercepted in India and returned to Dubai, after which no news came out of her, though by Dubai sources she was well. Allegedly Princess Hayā recently learned that the daughter was held in precarious circumstances and she became afraid for her own and her children’s life, so that is why she decided to leave now.

This version is now all over the Western press, and even getting quite an attention in the Arabic newspapers as this scandalous approach now overshadows all other possible explanations. Several things are, however, puzzling and noteworthy. First of all, since the connection is not established at all between the two events it is rather strange why would the Princess get afraid for her life now, alter a year or so, considering she had nothing to do with the Laṭīfa’s escape, not even allegedly, and she is not Princess Hayā’s daughter. She might disapprove what happened to the Royal Princess, but it is rather obscure why would that push her to run for her life. Noticeable how casually Western press makes an open scandal about the emir, who in general he lives a lavish, but not at all scandalous lifestyle. He is possibly the most known in the West among the emirs and indeed the economic marvel achieved in Dubai in the recent decades has much to do with him and his visionary approaches. Which were extremely successful until the 2008 economic crisis. It is true that in recent years the Emirates seriously damaged its reputation with the involvement in all regional disputes, most outrageous among them the massacres done in Yemen, but Muḥammad ibn Rāšid in fact had nothing to do with these decisions. As much as it is known he was always against these and the recent quarrels between him and the ruling elite in Abū Zabī was the direct result of his criticism over the Ibn Zāyid’s brothers’ politics as he viewed this extremely harmful to the UAE. Yet while the Western press has great time mocking the possibly most capable ruler in the Emirates, the same sources had almost no criticism over Muḥammad ibn Zāyid taking part in a bloodbath in Yemen, and almost all internal conflict of the region.

Likewise interesting the casualty how Western diplomats like to “help out” Dubai royalties to escape. Once a French, and now a German. Though no questions are raised how this all fit into the rules of international affairs. Not to mention the most logical question, the interest behind their apparent generosity.

The approach is also interesting as it completely derails discourse from another possible explanation, which was raised immediately after her escape. And here dates are important. As we discussed last week, on 1 May King II. ‘Abd Allah sacked the highest secret service and military advisors, even part of the royal court and it was rumored to be an answer to a coup attempt. He did this even though the country was preparing for a major joint military drill abroad, which started in 21 June 2019. With none other than the Emirates. This, Exercise at–Tawābit al-Qawiyya 1 (The Strong Constants) is the first ever to happen between these two states, officially aimed to boost bilateral cooperation in military and anti-terrorist dimensions, and was prepared for months. Even though there is no military agreement or any joint military protocol between the two states. Which makes it curious why the Jordanian monarch sacked most of his senior staff not much before that. He even visited the drill on 26 June, which makes it his first journey to Abū Zabī for a very long time now. Now if the rumors are true that the emir of Dubai specifically forbid his wife to hold any connections with the Muḥammad ibn Zāyid and his brother, foreign minister ‘Abd Allah ibn Zāyid there might just be interesting coincidences. As sources suggested immediately after her surprising escape, Princess Hayā might had a lot to do with the rumored coup attempt in Jordan in favor of his brother, ‘Alī. She might have been the connection between the plotters and the Emirati services behind the coup, as she could hold connection within Jordan without raising much suspicion.

Let suppose this is true! Had the coup succeeded she could have had a favorable government, possibly important roles even in the new Jordan, to where she could retire with ease. The failure of the coup and the complete dismantlement of the conspiring cells must have caused Princess Hayā to worry, since it was logical to assume that it is only a matter of time until her involvement and connections to Abū Zabī leaders becomes clear. And reports suggested that she disappeared from the public in May, so not much after the failed coup. The visit of his half-brother II. ‘Abd Allah to Abū Zabī, now securing his rule, might have came to discuss the matter with Abū Zabī. Naturally after the such an attempt the logical following step would be to distance himself from the Emirates, but as we saw last week that is something he simply cannot do. Therefore it is logical to assume that he came to sort out of the matter giving assurances to Muḥammad ibn Zāyid for a more the lenient foreign policy, including the deal of the century. And only more than a week after the visit Princes Hayā escaped. Now it is easy to understand why she didn’t go to Jordan. Having the two possible scenarios compared the latter fits the timeline much more.

Though that would still leave the question open, why Abū Zabī would support a coup in Jordan, why would that upset Dubai, and why the apparent affection of Western diplomats for Dubai royalties. These, just like the sudden death of yet another Emirati prince in the UK also this week, can be better understood in the context of internal politics within the Emirates, and the gradual rise of Muḥammad ibn Zāyid to be the effective ruler of the country.

The rise of Abū Zabī

Indeed the Emirates and its inner politics can be puzzling for outsides, since it is a federative monarchy. The state, or better put the states within the union were all British dominions until 1971, when along with the other two similar possessions, Qatar and Bahrain were given independence. The initial idea was a full union between all nine former British colonies, but for reservations by Bahrain the new state, what we know today as United Arab Emirates was formed in 1971 by six emirates. The following year the seventh, Ra’s al-Hayma joined the union, but Bahrain and Qatar chose to stay independent ever since. Regardless the merger the union was not an easy venture as most states were eager to hold on to their internal freedom. Therefore, partially for the charisma of Abū Zabī monarch, Zāyid ibn Sulṭān Āl Nahyān an agreement was made under which two executive bodies, Federal Supreme Council (FSC) made up by the seven rulers of the individual emirates, and the partially elected 40 membered Federal National Council (FNC) govern the state in all joint affairs. Externally the UAE is represented by Federal President – always the ruler of Abū Zabī – and the Federal Vice President – the ruler of Dubai -, while the latter usually holds on to the position of Prime Minister as well. All major appointments are done by the FDC in a collective decision, though leading posts are given to the two major states, Abū Zabī and Dubai. The general idea was that the state would be internally governed by the respected emirs in their own states, but externally follow a neutral foreign policy under the leadership of Zāyid ibn Sulṭān. The political leadership was given to Abū Zabī, while Dubai chose a path of openness to the outside world and in time became the economic engine in the state. Therefore one visits the UAE might be surprised to find that there are major differences in laws and practices from one emirate to the other.

That careful balance suited everyone as all could pursue their own vision for their own state and peoples, and while prominence was given to Abū Zabī, no one could gain overpower in the expense of the other rulers. Who in return blocked all attempts for further unification of personal power by just one ruler. That fitted well as long as Zāyid ibn Sulṭān was alive. When he died in 2004, however, things started to change both in the internal structure and the position of the UAE in the region, which was caused by the rapid rise of a new generation of rulers. After Zāyid ibn Sulṭān his eldest son, Halīfa ibn Zāyid took over his father posts, but due to his ill health he started to rely more and more on his younger half-brother, Muḥammad ibn Zāyid, especially after he suffered a major stroke in 2014. Halīfa ibn Zāyid is still the official head of the state, but by now Muḥammad ibn Zāyid practically took over state affairs, which he was pretty much running since 2004. In that he can count on his closest ally, his younger full-brother and Foreign Minister since 2006, ‘Abd Allah. The ambition of Muḥammad ibn Zāyid was clear from the beginning to transform the state to more centrally run one under his own rule, but because of the internal structure he faced serious difficulties. In such a pattern he chose to boost his standing in a field left open for him, foreign policy. Which meant a gradual break with the UAE’s passive, cooperative role in the region to a more active, and consequently aggressive stature. And accordingly, he had to slowly subdue or sideline all the other emirs. The two most formidable ones were the economical giant Dubai, and the famously conservative aš-Šāriqa.

The first big opportunity to curb the influence of Dubai came in 2009, by the global economic crisis in the previous year. Though usually the UAE and Dubai within it is considered to be an oil-gas based economy, which is not false at all, Dubai made significant steps to diversify its economy, more based on trade, banking services, and most of all real estate development. The Palm Island and World Island projects were the prime examples of that, but also it should not be forgotten that Dubai airport and the Emirates Airline made Dubai the center of transport and trade in the Gulf. Dubai was still investing heavily in real estate, when the crisis came hit the UAE. And since the whole crisis started in the real estate sector it was a huge blow to Dubai. Especially since the other pillar of the UAE’s economy, oil export, was also experiencing heavily problems, as oil prices at that time were all time low. Unimaginable even a few years before, Dubai arrived to the point it could not manage its $26 billion debts and asked for help from both the other emirates and the federative body. By the IMF report of 2010 Dubai was shrinking rapidly and only became stabilized by a complex aid fund package put together by Abū Zabī. Which practically meant that Abū Zabī managed to gain a limited financial control over Dubai, since much of the relief fund was provided by the Central Bank, and came not in the form of loans, but almost exclusively in guarantees for Dubai’s debt. Meaning Dubai still had to manage its problem mostly on its own, but became significantly dependent on the good will of Abū Zabī. Though Dubai mostly recovered since than, the problem is still serious and more and more reports describe Dubai as becoming a “ghost town” as tourism and foreign companies started to leave the emirate.

In this context Dubai, already experiencing Chine economic penetration and its former investment oriented growth model failing, needs peace and realignment in regional thinking. The least it needs is trouble in the Gulf and a war with Iran. The very climate of the possible war with Iran is devastating for Dubai now, since as we mentioned before, Chinese trade projects are to shift the center of economy in the Gulf to Qatar. With which cooperation is now impossible, given the UAE along with Saudi Arabia and Egypt are conducting an economic war on Doha for two years. Which further benefits Qatar in this context, since Doha pulled closer to Iran. Therefore if any war comes with Tehran no doubt retaliation will come upon the UAE instantly, but not on Qatar. So investments prefer Doha now even more. And that is the source of a major rift now, along many other similar problems between Dubai and Abū Zabī.

Muḥammad ibn Zāyid expanded his own influence through foreign policy in support for the USA. Taking part in Afghanistan and Iraq already managed to put the two Ibn Zāyid brothers on the international scene. That is very significant in the last decade or so, since the beginning the so called “Arab Spring”. In all majors turns the Emirates managed to tactically hide behind the back of Saudi Arabia, but get involved in all regional conflicts from Libya to Egypt, all the way to Yemen and Qatar. Should we not forget that in the beginning of this major regional restructuring Qatar was the practical caretaker of Riyadh, and managed to gain significant economic gains. All that was taken over by the Emirates after 2013, when the still mysterious government restructuring happened in Doha. As for only one example, Qatar was the biggest supporter the Mursī government in Egypt at one point even rumored to buy the pyramids, but after the coup of as-Sīsī the Emirates took over all Qatari possessions. Which was triumphantly expressed in 2017 at the opening of the Muḥammad Nağīb Military Base – now the biggest one in Egypt -, where President as-Sīsī was parading with none other than

Muḥammad ibn Zāyid – and some client leaders like General Ḥaftar from Libya -, while the biggest Saudi royalties were absent. That explains why Muḥammad ibn Zāyid is eager to support the Saudi Crown Prince now. Not only since he is being just like him, only much less talented, but also because as long as the Saudi leadership is so engaged internally the Crown Prince needs a stabile supporter in the region, even against his own family. While the other end of the bargain is the this way the Ibn Zāyid brothers can push the much bigger and stronger neighbor ahead of themselves, while being free to depart in any convenient occasion. As is the case now in Yemen, or the conflict with Iran.

Most of these foreign projects were covert operations performed by the Air Force and provided logistical support along with financial, tactical and intelligence backing to supported local allies. But the biggest one was the participation in Yemen since 2015, where the UAE put troops on the ground. That served Muḥammad ibn Zāyid so far the best. In the war against Yemen Muḥammad ibn Zāyid managed to significantly expand his control over his competition, even against Riyadh, and doing so he was either extremely lucky, breathtakingly cunning, or just outright ruthless.

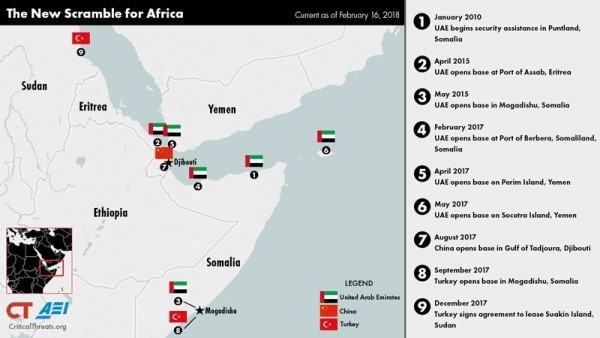

When the war started in Yemen it was launched in the name of a broad coalition, but was practically driven by Saudi Arabia, the Emirates and though reluctantly, but by Qatar. Thought the latter soon departed. They managed to convince – or tactically force – other states, mostly Arabs, like Egypt, Sudan, Morocco, but even Pakistan to put their much more capable forces on the ground and they restricted their operation mostly to air raids. Only gradually Saudi moved in from the north, while the UAE took positions along the coast, mostly in the south. The operation officially aimed to restore ‘Abd Rabbihi Hādī, former Yemeni President to power, who was deposed by the practical overtake of the al-Ḥūtī Movement. Since the movement is Shia and holds close ties to Tehran and its allies, the semi-official aim was to cut the growing Iranian influence behind the Saudis’ back. Also among the semi-officials aims were to gain hold of strategic sections of the country, like the major ports, the island of Socotra and the southern entrance of the Red Sea. For which aim the UAE set up a military base in Eritrea in 2015. That is the second ever official military base solely run by the

UAE on foreign soil, the first in Somalia in 2010, which is a major change in the foreign policy since the days on Zāyid, considering since then they build another four in the region. And given the supreme head of the Emirati Armed Forces is Muḥammad ibn Zāyid, these can all be attributed to his name.

The war on Yemen brought unprecedented inner cohesion, at least seemingly, in the UAE, which has much to do with sudden catastrophes. The UAE put significant amount of troops on the ground compared to its relatively small size. These consist of three distinct types. The first is some 1500 professional officers and trainers, which are building up loyal Yemeni troops under Emirati supervision, a so far limited success. The second group is made up of Yemeni mercenaries officially also doing training, but presumably they provide most of the guard and control services. The third group, the real fighting force, is around 1800 people, mostly mercenaries from Colombia, Panama, San Salvador, Chile and Eritrea, supplemented by Emirati Special Forces under the direct command of the Emirate Presidential Guards. Though recently both Western and Arabic sources claimed that the UAE also shifted Dā‘iš fighters to Yemen under its supervision, and even Human Rights Watch criticized Abū Zabī for the war crimes its troops commit. Nonetheless the UAE managed to take hold of valuable parts Yemen, mostly in the south and the operation seemed to be successful, until recently, when news suggested that Abū Zabī already started to pull out.

That might seem to be a failure after all, but not so much for Abū Zabī. But how and what does it have to to with the growing tension with Iran? Does the story of Princess Hayā and the recent death of another Emirati prince has anything to do with these? That is where we shall continue next week.