It has been two weeks that the Ṭālebān Movement overrun Kabul. Despite the allegedly surprising victory of a terrorist organization, the cooperation between this armed group and the Western powers occupying the country seem to work well.

This week we continue looking into the less obvious, or at least less presented implications of this development. Much of what we see, or the mass media shows us is far from being the reality we face in this matter. But the case’s importance goes far beyond Afghanistan, as many of the technics used here have been seen before and surely this is not the last time to be used. And there are two other countries in the region which face American occupation today, but Washington claims to leave soon. These are Iraq and Syria.

The world was shocked by the sudden overwhelming victory of the Ṭālebān. At least allegedly, as last we saw that there was little reason to be surprised. We saw that the Americans and the Afghan government set up by them knew perfectly well what is coming. But today we face a new reality. A reality, in which an internationally recognized terrorist organization became the ruling power in a county. How does this development affect the regional powers and the neighbors? How can they cope with a new “terrorist” neighbor? How does the formal members of the previous government deal with the situation? Is really the Ṭālebān everyone’s enemy?

The new realities

As we saw last week the Americans were preparing for an overall pullout and they knew well what were they doing. But were other powers prepared for this development? What could have been the scenarios for the Americans knowing full well that upon their leave the Ṭālebān will be the ruling power in Afghanistan?

The first logical question is why would the Americans arrange such situation? A situation, in which the Ṭālebān came to rule Afghanistan after twenty years waging a war, which eventually seems to have reached an end without any achievement.

Looking at the map the strategic importance of Afghanistan seems obvious, even without the potential use and resources of this state. It is right next to China, Iran and former Soviet Central Asia states still strongly under Russian influence. All these states are high on the American agenda to be confronted, or contained at least in a level. And also there is the industrial giant India, which had plans to invest in Afghanistan’s rare mineral mines. And for that aim India invested heavily in the Iranian port of Čābahār, which was supposed to work as a pathway to Afghanistan. And there is also Pakistan, a state formally strong ally of the Washington, especially in the covert war waged against the Soviet Union by creating the Ṭālebān at the first place. Yet Pakistan recently is not as an obvious ally anymore, and its strategic role, or use is somewhat questionable for Washington today.

So it is clear that leaving a troublesome neighbor behind for both China, Iran and Russia is not necessarily a bad thing for Washington. Recently in a number of debates American analysts argued that while the Ṭālebān is not anymore a direct threat to the US, the real loser by a Ṭālebān Afghanistan is Iran. Because in the late ‘90s Tehran almost went to war with the Ṭālebān, so surely it will be a huge threat to Iran, which will divert its attention from the more pressing Persian Gulf scene. This also can mean a barrier between China and Iran, while recently Beijing made a strategic partnership with Iran, the Chinese economy needs the resources of Iran and sees benefit in appearing at the Persian Gulf. There is logic in leaving such a problematic entity behind, which would mean an obstacle for all of its neighbors. It would bog them down while the internal war in Afghanistan goes on, but this operation would not require American troops and efforts. But are these states ready to deal with the situation? Since we saw last week that the American pullout was built up in the last two years with great detail, surely they did not sit idle. Surely they as well prepared plans for all scenarios.

Iran and the Ṭālebān

Indeed the history of Iran and the Ṭālebān is a troubled one. Upon the failure of the Afghan government left behind by the Soviets Iran supported the Northern Alliance, practically anyone against the Ṭālebān to hold up the emergence of a terrorist state at their doorstep. This change meant a major security threat to Iran in two ways. First and most directly that would have meant terrorist incursions against Iran along a long and hardly defendable border. Secondly the flow of refugees meant a security and economic burden on Iran, and indeed eventually millions of Afghan refugees settled in country. For these reasons Teheran wanted to slow down the Ṭālebān takeover, or prevent their victory if possible. This almost led to war, which was only prevented by intense U.N. mediation, and by careful reasoning in Tehran that a military operation has no exit strategy.

This cold relation eventually ended with the American invasion in Afghanistan, which Iran handled somewhat indifferently. On the one hand the collapse of the Ṭālebān state was a relief, but on the other the American military presence along their Eastern border was anything but favorable. That brought the two former adversaries closer and a number of former Afghan officials and even Ṭālebān members found audience in Tehran. Iran gave covert support for the Afghan insurgents bogging down the Americans, and this created opportunities to find allies within Afghanistan. This was the beginning for the planning what happens when the Americans leave one day.

Now Iranian analysts point out that the Ṭālebān of the ‘90s is not the Ṭālebān they face today. As we shall see that is very much correct. The transformation is huge. But Tehran was not betting solely on the idea of a “tamed” Ṭālebān and helped to build up allies. The most famous and most cited is the group mostly made up by the Hazara ethnicity is the Fāṭimiyyūn Brigade. This ideological indoctrinated paramilitary group was allegedly formed and trained in Syria fighting Western sponsored terrorist groups on the side of the Syrian state. While their true significance in Syria is heavily disputed, nonetheless they are an important asset, which is acknowledged by Iranian analysts today. The Hazara ethnic group is most significant in the north of Afghanistan around the power of based of Uzbek warlord ‘Abd ar-Rašīd Dostum, who is also not a particular friend of the Ṭālebān today. Giving support to him and having a hand within Afghanistan can by a huge asset while negotiating with the Ṭālebān. And the Fāṭimiyyūn is just one of these Iranian projects.

Tehran also had considered the eventuality of the Ṭālebān retuning to power. And for that aim they made contact in time to prevent yet another warlike situation. It is less known when the contact started, though allegations are numerous that Iran sheltered some Ṭālebān officials during the years of the American occupation, but the official breakthrough came in July 2021. On 7 July 2021 the “Dialogue between Afghans” conference started in Tehran, where not only representatives of the by now fallen Afghan government were present, but also those of the Ṭālebān. In that Iranian Foreign Minister Moḥammad Ğavād Ẓarīf met with the same Mullā ‘Abd al-Ġanī Barādar, who led the Ṭālebān “diplomatic mission” in Qatar.

The exact results of the negotiations are less known, put in the conference Minister Ẓarīf said: “We confirm the commitment of Iran to give help to achieve comprehensive social, economic and political progress after peace was achieved in this country”. That does not openly state, but hints that Tehran was prepared to deal with a completely new government in Kabul after the Americans left. And it is not surprising to see that Tehran officially welcomed the “victory of the Afghan people repulsing the Americans”. What was outlined that Iran is ready to accept the reality of a Ṭālebān government and grant political and economic support, given this new government restrains itself and departs from the former aggressive behavior.

This is the best possible scenario for Tehran. Seeing a government not being a friend of Washington and not hosting American military bases, for which in exchange economy cooperation can be offered. And this can be advantageous, if China indeed builds an economic corridor here. But to secure the bargain Tehran has paramilitary allies within Afghanistan, which can be friend, but also an obstacle in case the Ṭālebān turns against Tehran.

China and the Ṭālebān

China had a much less troublesome past with the militant group and has the advance of a long-known policy of not interfering in the inner political conditions of any state they make business with. And sure, China means business when it comes to Afghanistan. It already invested heavily in the neighboring Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, it made a strategic partnership this year with Iran to which Afghanistan can be an important corridor, and Afghanistan is relatively rich in rare earth minerals. To which India, an economy rival of China had an eye on, but now China is ready to take over these positions. China is already a producer of some 55% of the global output of these vital minerals, which means huge experience for this robust economic and logistical giant. Afghan rare earth minerals can easily find market via China, which is has a potential of huge revenues for the new Afghan government. This combined with industrial and infrastructural investments can mean a huge incentive for the Ṭālebān that now business is more favorable than war.

This could be the time when Ṭālebān not only wins a war, but wins the peace. By achieving stability – with whatever Draconian means – can be the foundation of massive economic development, which was only promised by the Americans, but never achieved. And on 13 July 2021, so even before the takeover of Kabul, Ṭālebān spokesman in Doha welcomed the potential Chinese investments in Afghanistan. He did not go into the specifics, but in light of these details it is not hard to guess what he meant. This of course did not come out of the blue. Negotiations between the two sides were well on the way. On 28 July 2021 the same Mullā ‘Abd al-Ġanī Barādar met Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi in China, who the same month made fruitful agreements in Iran.

Once again, the first, or second leader of an international terrorist organization, who spent years in prison in Pakistan and was released by American pressure was traveling around the world and making international agreements. Trivial matter, but worths to ask: With what passport, and by which airlines was he traveling so freely in a world, where ordinary citizens still face huge restrictions by COVID? And this was weeks before even the Ṭālebān came close to Kabul, when the mass media was still reassuring that it will take months before they take the capital, even in worts case scenarios. The answer is, to course, business.

Russia and the Ṭālebān

After all that it would probably not be surprising to see the same Afghan delegation meeting with Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, or even President Putin for that matter, but no such official meeting took place. In light of their past it is not all that surprising. Yet the Russian reactions are puzzling.

On 17 August this year Lavrov said that “…we see encouraging signs from Taliban…”, but also that Russia in in no hurry to recognize Ṭālebān government. Yet he also said that Russia was ready for Ṭālebān’s win and were in contact with it for at least seven years. While also emphasizing that Moscow still recognizes the Ṭālebān as a terrorist organization.

This attitude, which is not peculiar for Russia, can be somewhat understood by earlier statements in a press conference on 16 July 2021. Though Lavrov was diplomatic, the idea is clearly explained that the U.S. saw interest in leaving behind chaos and a military threat in the neighborhood of its most potent rivals to keep them bogged down with a highly volatile and unsolvable situation, in which eventually came back as a mediator. However, most neighbors also had contacts within Afghanistan and pressured the newly emerging power group that cooperation and peaceful contacts are more beneficial.

The same is true to Russia, which has less direct economic interests in Afghanistan, but its Central Asia allies need security. And that it a priority for Moscow, while economic cooperation with Iran and China here as well lucrative. These matters are much more important for practically all neighbors than the exact nature of the Afghan government. In other words, for Russia just like for all neighbors a “tamed” and moderated but stabile Ṭālebān rule is more favorable than chaos.

Even the West

All over the Western press we can see statements that what happened in Afghanistan is a surprise and a total failure of the West, or the Western values. We already saw that there was no surprise. But the anger of the European powers is understandable, as the U.S. pulled out casually leaving them without clear explanation and having to deal with an ordinal of evacuation. They went in to Afghanistan by Washington’s request and were left with a controversial situation they cannot really explain.

At the end a terrorist organization took over the country, which they fought for twenty years. It is indeed hard to sell as anything else than a huge failure. Yet on 28 August British Prime Minister Boris Johnson held extensive talks with his German colleague Angela Merkel on the situation, and they outlined two main issues. There must be international efforts and help to prevent a humanitarian crisis, and there can be recognition for and engagement with a Ṭālebān given they give safe passage to all who want to leave Afghanistan. And they have already admitted the relocation of some 15 thousand people above the diplomatic staff.

That means to meeting certain requirements the West is ready to pour huge funds and investments into Afghanistan regardless of being taken over by a terrorist organization. It is a noteworthy shift from the position even couple months ago. There are no talks about defeating the Ṭālebān anymore, but there are offers of funds. It is a puzzling behavior, considering they are far from Afghanistan with no direct security, or economic interests here. In other words they could afford to just leave Afghanistan behind without dealing with the new government.

The American connection

As we could see, the American policy was to leave Afghanistan as soon as possible. That is because its enemies managed to wear down the American forces here, which are ever more needed in more important fields. Washington could not make a steady foothold here to be the ideal bridgehead – as they imagined it twenty years ago – against Iran, Russia, China and India. But it was more favorable to leave a volatile situation behind, which is a menace to all these rivals. It seems to have failed largely, but there are many details, which show that a possible good Ṭālebān-American understanding can come around.

After all, it is a confusing scene to see around Kabul airport now, where the two former (?) enemies not only face each other every day for two weeks now, but they even need to cooperate to manage the chaos. Several videos show that despite the chaos within and around the airport there are checkpoints all around it where cooperation is working fine. While inside mostly American troops control the entry points, outside ordinary Ṭālebān soldiers and the Badr Battalion keep order. The same Badr Battalion, which was one of the most trained special force of the Afghan army, until they joined the Ṭālebān and secured their entry to the capital. These scenes give out a confusing picture to just what extent the former Afghan army “fell apart”, switched sides, or became incorporated to the new realities. And several ordinary Ṭālebān soldiers confirmed that they only allow those into the airport, who have to proper papers, which is determined by the Americans.

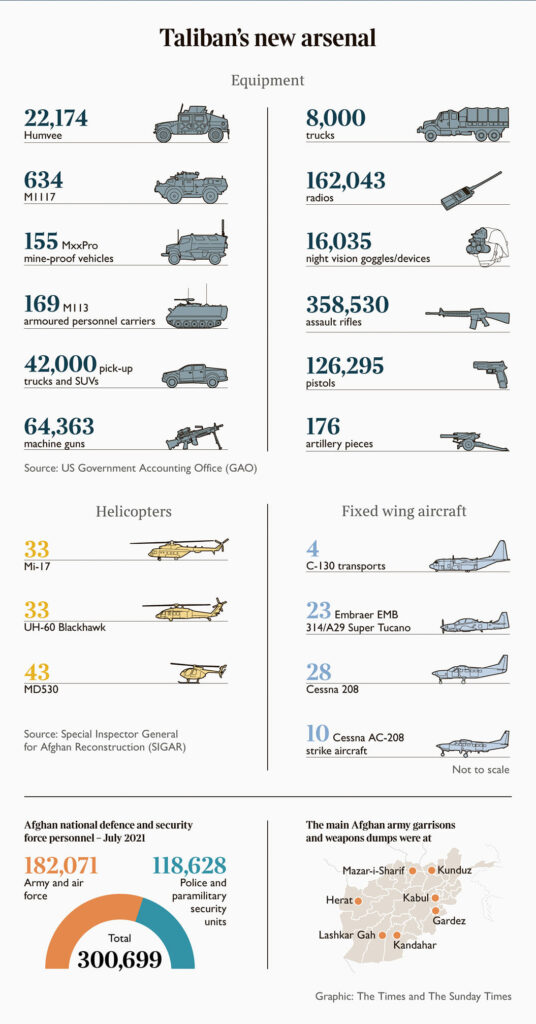

It is a known rule that after a major military operation ended the shipping of the equipment used, mostly the vehicles and arms is so costly that it is best “gifted away” to allies to cut the costs. Now the Americans can hardly think about something like this, yet their result is puzzling given the pullout was planned for at least two years. So Washington simply left most of its assets to its Afghan allies in the military bases. And the reasoning for that is that unfortunately all that was apprehended by the Ṭālebān. But just what exactly was left behind by the Americans?

It is interesting to note that the Americans now not only show no interest to retake at least some of these armaments, but to at least destroy them. After all the result is that they massively armed a terrorist movement. With whom, or with their successors Washington still has plans.

A new Ṭālebān?

We saw that the behavior of most states towards the Ṭālebān changed fundamentally to what it was twenty years ago. The hinted reasoning is that this is not the same Ṭālebān anymore. This Ṭālebān talks about human rights, women’s rights, makes promises, grants amnesties and make international commitments. This is truly not the behavior we saw in the ‘90s, when it was rough underground movement taking over a county gradually. The Ṭālebān spokesman in Qatar and by now even in Afghanistan makes almost daily press conferences to all agencies of the world, address issues and respond smartly.

Most of these promises are yet to be seen in practice and naturally many are skeptical. But there is a much more fundamental change in the nature of the Ṭālebān. While in the ‘90 it was just one of the many small fighting groups, which gradually subdued or annihilated the others, it had a very coherent hierarchy led by one man, Mullā ‘Umar. Today the Ṭālebān is practically one umbrella, which in no time incorporated whole army battalions with ease. If that is indeed the truth. Yet its leadership is not under one man anymore. Despite the division we addressed last week between the local and the Qatar based leadership, there seems to be a collective, a ruling council, which is somewhat alien of such movements.

And this ruling council is so inclusive that it is ready for a power-share mechanism, by which the new government would give posts to tribal leaders and former government figures. And not just anyone. According to reports the new ruling council of Afghanistan will incorporate former President Ḥamīd Karzāy and former Foreign Minister and Chief Executive of Afghanistan ‘Abd Allah ‘Abd Allah, who since May 2020 was the Chairman of the High Council for National Reconciliation. Thus he was the head of the government delegation negotiating with the Ṭālebān in Qatar. He was the main rival of former President Ašraf Ġanī. And he was lobbying for a settlement with the Ṭālebān even a year ago.

In light of this it is less surprising to see that the military resistance still in control in the Panğšīr valley rumored to keep fighting the Ṭālebān is not that determined anymore. Its most prominent leader Aḥmad Mas‘ūd at one point was reported to be ready to recognize the Ṭālebān. And recently this forming resistance group, which meets little support from abroad made a ceasefire with the new rulers of Kabul.

What we see is in fact the merger of the Ṭālebān and the top echelons of the former Afghan leadership. Which really means a more suitable, “tamed” movement, far from being the rouge organization what it used to be. The question is where its allegiance will lie.

A dangerous precedent

Why is Afghanistan immensely important for the Middle East? There are lessons to be learned about the changing nature of politics. But we should not loose sight of the facts that Afghanistan is not the only pointless and endless military engagement of America in the Middle East. Most directly there is its questionable presence in Iraq, and its illegal presence in Syria.

In Iraq the parliament has already accepted a resolution demanding immediate withdrawal of the American troops from the country and there is a growing resistance supported by Iran. The current Iraqi government still in a fragile state held intensive negotiations with the U.S. to achieve a pullout. Biden has promised just that until 31 December 2021, but until then parliamentary elections are coming up. Iraq struggles with terrorist groups, most importantly with the Dā‘iš, but is adamant about American pullout. Surely a handover of assets and power using the Afghan script is not viable in Iraq, though it was experimented with in 2014. That was the last time the Americans “tried to leave” Iraq. And unlike Afghanistan, here the U.S. wants to stay for good. So Baghdad has good reason to fear chaos upon a possible American pullout.

Syria is just as complicated. With most states rebuilding their relations with Damascus and even Arab states heavily pressuring Washington to leave Syria, it is clear that the current situation cannot go on for long. But the U.S. does not like to leave its positions behind before securing interests. So we can expect the increase of Qasad activity in Eastern Syrian under American guidance in the soon future before major steps are made for a pullout. Which might come only after Iraq, if that ever happens.

It is feared already that the Afghan scenario might repeat itself in Iraq soon. And Iraq is indeed in a very volatile situation now ahead of the upcoming elections. And that shall be our topic for next week.