The matter of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) is a major issue for Ethiopia’s downstream neighbors Sudan and Egypt, ever since constructions began in 2011. For quite some time it was a distant menace for Egypt, which had way bigger problems at the time. Since Egyptian President ‘Abd al-Fattāḥ as-Sīsī took power in the summer of 2013, however, there were constant clashes between Egypt and Ethiopia about the project. Sudan took Egypt’s side in the conflict in recent years, which gave more weight to Cairo. The three sides reached a partial understanding in 2014, but cooperation gradually broke down as the construction progressed and there was no progress on the final compromise.

In the last two years, the sparks were getting more frequent between Cairo and Addis Ababa, just like the suggestions on possible military action. Yet back in 2019, as the Libyan crisis and the confrontation with Turkey was at their height and by the summer of 2020 getting close to direct war, Egypt simply had no power to wage a two-front war. This matter, however, seems to be closed and the rift between Cairo and Ankara is closing fast, giving Egypt time and backing to finally stop Ethiopia.

Currently, the matter is so serious that there are almost daily suggestions by Cairo to actually bomb the dam. Which does not seem to be extremely difficult militarily, as the GERD is close to the Sudanese border and Khartoum seems to be on Cairo’s side. Egypt is gaining regional support for its stance, and this comes at a time when Ethiopia is still weakened by armed unrest in its northern regions. As the last attempts for negotiations in Kinshasa on 6 April, 2021 broke down. The possibility of military action seems to be getting closer, as as-Sīsī already on 30 March in a speech in Suez promised action.

The matter of GERD is a complex and controversial one, as Egypt and Sudan are rightfully worried about the drop of the water flow. But at the same time they have a number of dams already on the Nile, meaning they want to prevent, or at least serious curtail Ethiopia from doing what they’ve done themselves. The issue of such a major investment project and turmoil around it naturally brought the attention of many states, even those of big powers.

By now it a regional crisis, in which Egypt has a lot to lose. Depending on the Nile and the Aswan dam so heavily we can understand why is it such a crucial matter. But much less publicly Cairo has another reason to worry if the water flow becomes less. For years now it is conducting a major project at the end of the Nile. This also soon might reach its end, which might make Egypt not the final destination of the Nile anymore.

This is the point, where the matter becomes much more complex, and much more important regionally.

Who has the Nile?

Water distribution in international law is a very long topic. Not going deep into the details, Ethiopia does have all the right to build a dam on the Blue Nile, given it has reached a compromise with the downstream neighbors, namely Sudan and Egypt. Given that they have a number of dams themselves – Sudan itself built and enlarged a number of them since the 2000’s – there can be a little moral objection to the plan.

Ethiopia has serious electric shortages, but the GERD could transform it to electricity supplier to its neighbors, including Sudan and Egypt. Meaning what they lose could be compensated, and at the same time, there is a significant agricultural benefit. A further argument for the Ethiopian dam that it could better regulate the seasonal floods on the Nile, which only last year caused huge devastation in Sudan.

On the other hand, Sudan and Egypt are rightfully worried about the loss of water. The Blue Nile provides the majority of the Nile’s water and almost all of the seasonal floods’ sediment. That would seriously affect their electricity production and their agricultural output. And the latter is a much more serious issue, especially for Egypt. Given both Sudan and Egypt has oil, the lost electricity can be compensated. Sudan also has the White Nile, which is not connected to Ethiopia, so it can circumvent the effects of the GERD. But Egypt only has the Nile to depend on. And, as we shall see, it has even bigger, though less public goals with the river.

However, since the beginning of the project, it became a matter of national sovereignty for both Egypt and Ethiopia. Egypt considers the river its own historical possession, the whole civilization was built upon it. So it is not easy to see another state changes its fate. As for Ethiopia, the Blue Nile starts from Ethiopia itself, so it is understandably a matter of national pride to do with it as they wish. This mentality was perfectly shown, when on July 2020 upon the completion of the first spillway the Ethiopian Foreign Minister stated: “… the Nile is ours”.

So beyond the huge economic, agricultural, national security, and environmental concerns, there is a question of national pride and sovereignty. Which in the Middle East rarely brought other than conflict.

A gradually escalating tension.

By now the Arabic media is full of suggestions that an Egyptian military action is unavoidable. That is both presents on the Arabic owned and in the Arab language foreign channels debates. But his is not at all a new issue. Ever since the construction started in 2011, the GERD project was criticized by Egypt. But back then Egypt was itself in turmoil. So it had a more compromising policy of showing support, only negotiation every step in the way to ensure a result less harmful for Egypt.

Since President as-Sīsī took power in 2013, he had more basis to deal with the situation, especially after 2015, by which he settled most of his pending major problems. Constructions on the GERD progress slow, and negotiations bore fruit when a tripartite agreement was reached in 2014 that joint commissions will discuss technical details to appease all parties.

The work of the joint committees, however, gradually broke down and both Egypt and Ethiopia started to deviate from the compromise evermore. Things started to spiral out since 2018, where Ethiopia elected Prime Minister Abiy Ahmad, who took the project as one of his personal quests. And pretty much since then, there was a secret war, or – a matter of viewpoint – a strange series of extreme coincidences. In May 2018 the first high-ranking officials were gunned down in the Ethiopian capital, then in July Simegnew Bekele, the main engineer and project manager of the GERD were found dead in Addis Ababa. He was obviously assassinated.

In November 2020 a series of clashes started against the Ethiopian armed forces in the north of the country, which led to the Tigray War, which spread out Eritrea as well. And that is still not completely over. It might just be a coincidence, but at that time the Egyptian press heavily reported on the war and it became one of the arguments of Cairo that such a project cannot be discussed with such a volatile and unstable country.

Negotiations went on and broke down periodically, always achieving delays in the completion, but never the solution. Which led Egypt to assume that Ethiopia eventually will finish the project by its own desires, no matter what. Since then the relations are on a collision course. Only at that time, Egypt was busy holding off Turkey in Libya. But since then this matter is over and the Egyptian-Turkish relations are rapidly improving.

In recent months there has been a significantly harsher tone by Egypt, and the support it gained increased, at least in the Arab world. On 30 March in an open speech at Suez President as-Sīsī said: “Don’t take even a drop of water from Egypt… all options are open, but the cooperation is better”. Most views hold that this counts to be the last warning, since then there is a preparation for war.

Tunisian President Qays Sa‘īd visited Cairo on 10 April and about the Ethiopian dam had the following to say: “… About the just distribution of the water, I say, and I repeat in front of the whole world. We are looking for a just solution, but Egypt’s national security is our security. Egypt’s position in any international forum will be our position”. Tunisian might be a small player in this conflict, but this statement shows how much the wind is changing, and that Egypt is seriously considering military action. On 15 April this position was shared by Saudi Arabia, by King Salmān himself, who openly hinted that Saudi Arabia is ready to assist Egypt, in case it is needed. For military considerations, this is a significant boost for Egypt.

Can it be done?

As we see by now Egypt is openly suggesting military action, the direct bombardment of the GERD to its foundations. This might seem possible by a precision hit on the dam, which can be achieved relatively easily, but for the desired result Egypt’s task is much bigger. A few missile hits might render the power plant inoperable and block further constructions for a while, but probably not damage the massive concrete wall on the level of breaking through. And here we are talking about three spillways. That would need a more intensive barrage, meaning more careful planning. This is fairly obvious at this point, since if it was that simple Egypt would have taken this step long ago.

Of course, the potential environmental impact has to be taken into consideration, meaning that with the collapse of the dam all the water stored in the reservoir would suddenly flood the Nile downstream causing huge damages in Sudan and Egypt as well. This is to be avoided, but at this point, Cairo is running out of options.

Assessing the possibility of a military strike Egypt has to evaluate two major factors. Can it be done from a military perspective, and can it be done politically?

From the military, or technical point of view, it should be kept in mind that Ethiopia by now is a land-locked country, meaning it is only accessible through another, there is direct access from international waters. Therefore bombarding the dam the Egyptian military needs cooperation from a country neighboring Ethiopia or has to strike via a country that is not in a position to pose serious complications. For the first one Sudan is the ideal partner. Khartoum is also highly concerned about the GERD project and would be happy to see it stopped. For two years now, since the ouster of former president al-Bašīr the government is practically in the hands of the military, and the Sudanese military has a historically good relation with its Egyptian counterpart. After all back in the old days al-Bašīr started his career in the Egyptian army. The dam itself is only 40 kilometers from the Sudanese border, meaning the Egyptian planes could enter Sudan undetected, refuel, and hit the target easily and intensively before major opposition can be mounted by the Ethiopia Air Force or air defense. This seems to be the most logical and direct way. Further supports this scenario the fact the in early April 2021 the Egyptian and the Sudanese air forces held a major joint exercise in Sudan under the telling name: Nusūr an-Nīl 2 (Eagles of the Nile 2).

However, Sudan is far from being stable at this point and has reasons not to risk an all-out war with Ethiopia now. Also, its government is on less than stable grounds since the coup two years ago and the normalization with Israel in late 2020. So it is doubtful if Sudan would allow this sort of action without a coordinated plan to meet the Ethiopian response. That is probably why we don’t hear the same heated threats from Khartoum, as we do from Cairo.

The other possibility would be to hit either from the sea, from the Saudi bases in Yemen, or the Emirati bases in Yemen, or Somalia. This way the Egyptian task force would either refuel in the air, or operate from a Saudi, or Emirati base in the region, and cross over Eritrea, Djibouti, or Somalia. None of these states have the capability to cause any complication for an Egyptian strike force. But the problem is that in all these scenarios the Egyptian planes would have to cross vast areas in Ethiopian airspace, which might be achieved on the way in, but the return would be costly.

There is of course the possibility of a mixed strategy. Either carrying out attacks from multiple sources, or hitting from Yemen, or Somalia, and leaving the Ethiopian airspace via Sudan. That would put much less stress on Sudan and Khartoum could evade repercussions easier, while the objections from Somalia, or Eritrea could be easily disregarded. But that would still need a high level of cooperation with Sudan. So far that seemed unlikely, but the recent warning from Saudi Arabia could signal that Riyadh and possibly Abū Zabī would pressure Khartoum to cooperate. That is because after the Gulf crisis with Qatar ended in the al-‘Alā GCC Summit Egypt rapidly started to distance itself from Saudi Arabia and the Emirates, while at the same time was solving its problems with Turkey. So it is favorable now, at least for Riyadh, to regain some Egyptian sympathy by supporting it in its conflict with Addis Ababa. The question is, how far would they be willing to go.

Assessing the military capabilities we have to bear in mind that while Ethiopia does not have the same military capabilities as Egypt and its mostly outdated Soviet-built air force is far inferior to the Egyptian one, it is still a force to be taken into consideration. And since the political conflict about the dam became severe in the last few years Addis Ababa took steps to equal out this disparity. On that Ethiopia relies on support from Israel.

Already in 2019, Ethiopia bought air defense systems from Russia, but the Pantsir-1 while being a capable model, if on its own insufficient to repel a possible Egyptian attack. Therefore Addis Ababa in May 2020 acquired Israeli SPYDER battalions and deployed them around the GERD. So while Ethiopia itself is largely vulnerable from the air, the dam itself is relatively protected, or at least great steps were taken to repel any military action. Yet this might not be enough, as experts pointed out that modern Rafale airplanes can outplay these air defenses, and the Ethiopian Air Force is no match against them. There is a fairly clear arms race between Egypt and Ethiopia about the dam, in which so far Cairo is gaining the upper hand.

Militarily speaking the strike can be done, and there are indications that a plan has already been developed, with or without Sudanese participation. The question is the environmental and diplomatic result. The environmental is risk is severe but might be secondary in the calculations. The diplomatic result, however, is much more complicated. Egypt has little to fear from Ethiopia directly, as the Ethiopian army is in no condition to seriously harm Egypt. The supposed strike might trigger an open war with Sudan, which is a deterrent, but Egypt can lend support to Sudan, and also it is not in the interest of Ethiopia to launch such a war. It has not much to gain from that beyond revenge, but a costly war after the collapse of the dam, and right after months of severe fights in the northern regions could be catastrophic to Prime Minister Abiy Ahmad’s government.

The much bigger question is how much support Cairo has, and if it is bigger than that of Ethiopia. If a military strike took place the international outrage will surely follow. Overall in the Arab and in the African fold Egypt has enough support to let such an action unpublished, or even openly support it and blame the conflict on Ethiopia. The West is much more occupied to take serious action, and other major powers, like Russia, or China have bigger interests in both of these countries to severe relations. Meaning that if we are talking about one decisive hit and not a war, and if there is enough Arab and African diplomatic support, Egypt can “get away with it”. A possible war with Sudan is a risk, but if sufficient financial and military guarantees are provided a Sudanese objection can be overcome. Sudan is an important provider of troops in Yemen for the Saudi war effort, an important ally of Egypt, and recently secured ties with Israel as well. So there would party to support Khartoum.

There is one state, however, which is heavily involved with both camps and has a major role to play. That is Israel.

The Israeli connection

Israel a significant role in the matter. Ethiopia has an outstanding role in the Israeli mindset, as it is home to the Ethiopian Jews, a community Jewish by religion, which started to migrate to Israel in the ’70s. Their number in Israel currently is around 80 to 120 thousand. Also in the Ethiopian Christian tradition, Israel has a pivotal role, as much of the Ethiopian transitions are closely tied to the ancient kingdom of Israel, and their form of Christianity is in many ways much closer to Judaism than most other Eastern Christian churches. There is a very significant moral, psychological connection, apart from the fact that Ethiopia is now a major entry gate for Israel to African relations. There are huge Israeli investments in Ethiopia. This includes the agricultural sector, but also telecommunications, which is seriously encouraged by Addis Ababa. Since Prime Minister Abiy Ahmad took office these investments skyrocketed, and one of the main projects is the GERD. Not even including its military connotations. So the failure of the GERD would not be specifically welcomed in Tel Aviv. And since Israel has official – and unofficially excellent – ties with Egypt, it has enough influence to dissuade as-Sīsī from military action. Given it seriously wants to.

Interestingly, however, Israel has interests in the other camp as well. The recent normalization with Sudan was diplomatically a major achievement, though it so far hasn’t reached an irreversible stage. If Israel would implicate itself in the matter on the Ethiopian side, it would surely not help to consolidate its recently gained foothold there.

But more important than that, there is a way bigger reason Israel would also be unhappy to see a serious drop in the Nile’s water level. It is rarely talked about, but in fact, the Nile is getting very close to reach Israel and right where it would be most beneficial for its agriculture, its southern part at the Negev desert.

Looking at the map this seems unbelievable, but the plan is not even new. Already in 1979, late Egyptian President as-Sādāt proposed to derive a section of the Nile to Jerusalem as part of the peace deal. According to the idea the water was intended to reach the Palestinians, but also be accessible by everyone in the area, thus stopping the conflict for arable land. Apart from the huge costs, allegedly, the real reason was the legal advice received by as-Sādāt not to make Egypt from the Nile’s destination country to one simply along its banks, as it would seriously change its legal status and in international forums, Israel would have a saying in how Cairo uses the river. The plan to deliver water from the Nile to Israel, thus making Israel part of the Nile’s stream, was never really given up. It was only put to hold until as-Sīsī picked it up once again sometime around 2016.

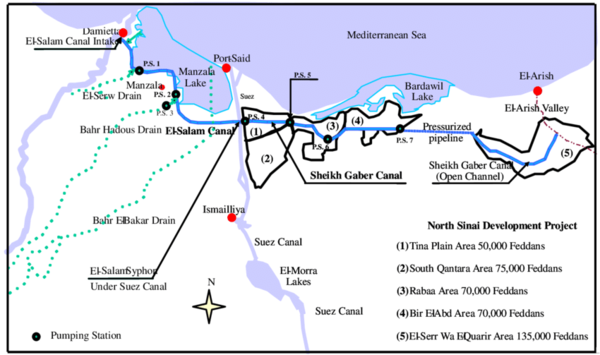

Though – at least officially – the idea to delivering the Nile to Israel was dropped, by the late ‘90 there was such a growth in Egypt’s population that the enlargement of arable lands and living areas as needed, and for that several major ideas were put forward. Most of these with significant financial help from Gulf countries were built later on, though various scales. One of these megaprojects was the North Sinai Development Project. By this the Nile would be partially rerouted at Damietta (Dumyāṭ) to the Peace Channel (Qanāt as-Salām), delivered to the Suez channel, crossed it in tunnels under the channel, and deliver a significant amount of water to the Sinai, making agriculture possible. Thus Egypt could gain some 400 thousand feddans (648 square miles) of land for agricultural production, create income, and urbanization in the area, thus further increasing stability. By late 2019 the channel has already crossed under the Suez Channel, and by December 2020 the Egyptian authorities proudly presented the initial success of the project.

The North Sinai Development Project contains 5 major areas of agricultural development. The fourth stage is Bi’r al-‘Abd, and that was reached in 2019. Though very little is announced about it, and strangely enough, the current Egyptian leadership never commented on the possibility of the Peace Channel reaching Israel, we can safely assume that the construction continued. Since there hasn’t been any announcement, we cannot confirm, but the project should be close by now to reach al-‘Arīš. Which is only some 40-50 kilometers from the Palestinian border, and the last major Egyptian urban center before it. This major construction is noteworthy for two reasons. There is very little information about it, and it is ongoing despite all security problems and insurgency in the area. This suggests that the project has special importance for Cairo, above most other development projects, which are regularly announced and celebrated.

Why is that so important in the matter of the GERD project? If Ethiopia finishes the dam and floods reservoirs, Egypt will have a significant loss in water and in seasonal floods, which will decrease its electric production at Lake Nasser, but more importantly, will jeopardize the whole North Sinai Development Project. There will simply not enough water for that.

That is where the Israeli role is significant. Tel Aviv currently plays for both camps. If Ethiopia finishes the GERD project, it can capitalize on its agricultural investments and might receive water transports. Technically that is feasible. There were such agreements even between Turkey and Israel, even if that did not materialize. Financially and strategically it would be a huge gain. Yet if the cards played right, Israel could approve an Egyptian military action, for which it could ask the completion of the Peace Channel from al-‘Arīš to the Negev Desert. Which would ease its water needs and gain further arable areas. This suggests that Israel is ready to back either camp, but would ask a heavy price for the support.

Currently, however, there is not a stable government in Israel. Netanyahu came out the winner in the recently held elections, but its allies could not gain a majority. On 6 April Israeli President Reuven Rivlin tasked Netanyahu to form a government, though he himself acknowledged that there is little chance he will succeed. This is the fifth election in Israel in the last three years and Netanyahu’s chances are getting smaller every time to continue. Considering that he is busy with forming a government and waging a secret war with Iran right now, this is the best possible opportunity for Egypt to act. Given its wishes.

On the verge of collapse

There is a clear preparation for war by Egypt. Less than a year ago President as-Sīsī was ready to go to war in Libya against Turkey, a much more formidable military power than Ethiopia. The threat was very real and though the war did not follow, we can see how much Ankara changed its position on Libya since then. It was not a totally empty threat, even though it faced serious objections from a number of regional countries.

Now with Ethiopia, there is no need for a long military engagement, “only” a limited strike. There is no major opposition either, while the number of supporters is gathering. The only state, which might seriously oppose such a military strike is Israel, which can be persuaded.

The last statements of President as-Sīsī and the joint military drills with the Sudanese Air Force leave little doubt that this is once again not an empty threat. Ethiopia has very little space to maneuver, but still has time to reach some sort of agreement or international mediation. However, the last rounds of negotiations in Kinshasa, which were said to be the “last effort”, left little hope for a compromise.

The possibility of a military conflict and a major environmental catastrophe is very real, and there seems to be very little international effort to stop it.