Almost a month ago, in mid-January, Iran bombarded positions deep inside Pakistan. Islamabad did not take the matter lightly and banned the Iranian ambassador from returning to Pakistan while at the same time, it recalled its ambassador in Tehran. Days later the Pakistani army hit back bombarding a village close to Sarāvān in Iran. Both sides claimed that in the respective attacks of the other mostly civilians died, while the justification in both cases was to strike at terrorist organizations.

Very suddenly, and almost out of thin air, the two countries both having massive armies were on the verge of going to war. Or so it seemed. Indeed, neither of these states takes it lightly when military operations are conducted on their soil by a foreign power, though terrorist and insurgent attacks are not uncommon to happen.

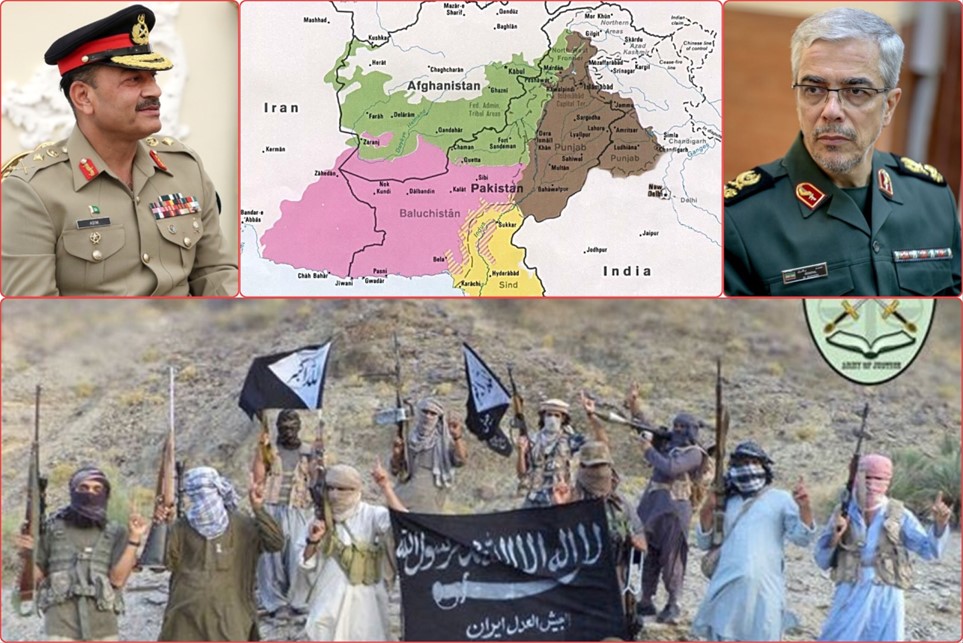

Yet, just as sudden as this storm broke out it settled down almost immediately. On 29 January, so less than two weeks after the initial Iranian strike the Iranian Foreign Minister was already in Islamabad in a meeting with the Chief of Staff of the Pakistani Army talking about cooperation on border security and fighting against common threats. They also vowed not to let foreign sides “drive a wedge” between the two neighbors, who otherwise have cordial ties with each other.

It was a peculiar incident at a very sensitive time. Both sides, though heavily protested about the military action of the other, claimed not to have struck the other side’s army, nor its civilian population, but separatist militants. As if they were fighting against the same problem, if not the same enemy. It also happened at a time when Iran was focusing on the developments in Palestinian fighting an extensive clandestine war with Tel Aviv, while Pakistan was gearing to general elections, the first time since a highly controversial power grab in 2022.

Why in such a sensitive time these two states almost go to war with each other, when overall the relations are good and they have little interest in the internal affairs of the other? Where did this sudden storm come from and where did it dissipate? Has it subsided, or is that just a brief pause, until much worse is coming?

The sudden chain of events

On 16 January the Iranian army using ballistic missiles and three or four drones bombarded two positions deep inside Pakistan’s Panjgur district in Balochistan Province. The number of casualties is disputed. Tehran Net mentioning the casualties only stated the positions it hit were hideouts of the Ğayš al-‘Adl terrorist organization and only to prevent an imminent terrorist attack against Iran. Islamabad claimed that two children were killed in the attacks not specifically mentioning what was hit. On the other hand, Ğayš al-‘Adl claimed that the homes of its members were bombarded killing children, though this indirectly corroborated with the Iranian version that indeed the target was this organization.

This Iranian attack came only one day after similar precision strikes in Erbil Iraq against a Mossad compound allegedly killing 4 Mossad operatives and in Idlib Syria. These attacks came in response to the deadly terrorist attacks in the Iranian city of Kermān on 3 January killing around 100 people and injuring around 200.

Pakistan immediately protested, recalled its ambassador, and forbade the Iranian ambassador to return to Islamabad, vowing that the incident would have its consequences. Indeed, in a country where the army and the security services are by large in control of the state, the army could not allow it to appear weak.

On 18 January under codename Operation Marg Bar Sarmačār – Death to Separatists – the Pakistani Air Force also using drones and missiles bombarded nine positions around the Iranian city of Sarāvān killing nine people. Tehran protested against the attack, which was the first time that a foreign state openly conducted an attack on Iranian soil since the end of the Iraq-Iran war, and stated that nine people were killed in the attacks, were “non-Iranians”. Pakistan claimed that the attack, which was a face-saving retaliation to Iran, targeted the positions of the Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA) and the Balochistan Liberation Front (BLF). Both separatist terrorist organizations are of Balūč ethnic origin, just like Ğayš al-‘Adl.

Despite the attacks and the lack of clarity about the exact targets or casualties, when the situation seemed to be boiling over diplomacy prevailed. Already on 18 January China offered mediation. But that was not needed. Tehran and Islamabad soon engaged in diplomatic talks promising that Iranian Foreign Minister Ḥosseyn Amīr ‘Abdollahiyān would soon visit Pakistan. Which he did and on 24 January in Islamabad he met both his Pakistani counterpart and Chief of Staff of the Pakistani Army General ‘Āṣim Munīr. The two sides carefully avoided mentioning what had just happened both focusing on turning the page on the events and vowing to avoid foreign parties “driving a wedge” between the neighbors. Both sides underlined that relations are good and strong both supporting the other, agreeing on protocols to enhance border control and security cooperation to prevent further incidents. Here it was also agreed that Iranian President Ebrāhīm Ra’īsī would soon visit Pakistan after the general elections in the country to further enhance cooperation.

The aftermath

With the seemingly cordial joint statements and new security protocols signed on 24 January, it appeared that whatever caused this brief crisis it was over and things went back to normal. But the matter is still not completely over.

On 17 January, so only one day after the Iranian strike and even before the Pakistani retaliation Ğayš al-‘Adl killed three members of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards at the Pakistani border including a major operation commander Colonel Ḥosseyn ‘Alī Ğavdānfar. Similar unconfirmed attacks were alleged on the Pakistani side of the border as well since then. On 24 February it was reported that the Iranian special forces entered Pakistani territory and killed one of Ğayš al-‘Adl’s top commanders Esmā‘īl Šāhbahš, though this hasn’t been confirmed by either government.

Yet it seems likely to be true, as on 23 February the Iranian Foreign Minister once again held extensive consultations with his Pakistani colleague stressing that both sides have to do more to implement the recently made security arrangements. Thus clearly showing a dissatisfaction with the results so far.

What is Ğayš al-‘Adl?

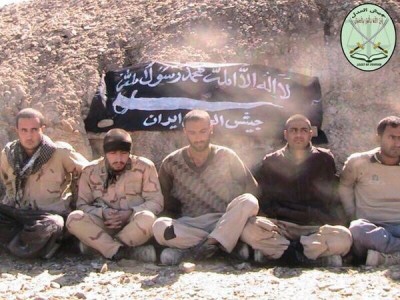

But what is Ğayš al-‘Adl – Army of Justice -, this relatively unknown terrorist organization that seemingly caused all this trouble? This militant organization is a Sunni group almost completely based on the Balūč people living in Iran and Pakistan, mostly active within Iran regularly carrying out attacks against the Iranian state. Though it is often claimed to be a separatist movement fighting for independence from Iran, the group officially claims to fight for better treatment for the Sunni Balūč people within the overwhelmingly Shia Iran.

The group is a resurfacing movement after its predecessor the Ğund Allah – Soldiers of God – was dismantled. The Ğund Allah group was rooted in the many separatist, or anti-Shia movements that had gained support from Iraq during the ‘80s, but after the Iraq-Iran war ended lost support. Within this wide range of activities, many ethnic groups were used against Tehran, including the Balūč. From the remains of these separatist groups around 2003 Ğund Allah was formed by its leader ‘Abd al-Malik Rīgī, soon organizing attacks against Iranian high-priority state and army officials, though mostly concentrating its activities on Iran’s Sīstān and Balūčistān Province. Its possibly biggest operation was the 2009 attack in the same province in Pīšīn killing 43 people, including the Deputy Commander of the Revolutionary Guards Land Forces at the time Nūr ‘Alī Šuštarī. The group already at that stage had strong ties to al-Qā‘ida and by Iranian claims also received support from Washington.

In 2010 ‘Abd al-Malik Rīgī was arrested. According to the Iranian state accounts he was arrested while traveling with fake documents from the Emirates to Kyrgyzstan when his plane was forced to ground in Iran, while other sources claim that he was arrested within Pakistan and handed over to Iran. Either way, Rīgī was soon sentenced and executed in the same year, which caused Ğund Allah to break apart into smaller groups more closely tied to al-Qā‘ida, only to reappear under the name Ğayš al-‘Adl around 2012. This came through the merger of several smaller movements that had broken off from Ğund Allah. At that time and for the next decade it mostly received support from Saudi Arabia, though Tehran always claimed heavy involvement by Washington and Tel Aviv as well.

The main center of its activities in the beginning was the border zone between Iran and Pakistan, mostly around Sarāvān killing Revolutionary Guards and border patrol forces in this remote mountainous terrain. They really gained fame in 2014 when they kidnapped five Iranian border guards and moved them to Pakistan. One of them was killed, while the four others were eventually released. At that time the scandal was a huge burden on then President Ḥasan Rōḥānī’s administration.

Sporadic attacks continued in later years and many times it happened that border guards were kidnapped and taken to Pakistan. The attacks soured after 2018 and the group’s biggest attack came in February 2019 with a suicide attack against the convoy of the Revolutionary Guards close to the Pakistani border killing 27 of its members and injuring another 13. At that time already Tehran summoned the Pakistani ambassador and vehemently protested the lack of serious action by Islamabad against the group. It was seen that the group acts freely within Pakistani territories receiving funds, planning operations, and carrying out attacks against Iran, regularly kidnapping people back to Pakistan.

These events launched a series of negotiations and meetings between top diplomats and military officials from both sides, as mostly Iran tried to achieve a more comprehensive cooperation with Pakistan to break Ğayš al-‘Adl. It should be highlighted that while Ğayš al-‘Adl mostly hides in Pakistan and carries out attacks in Iran, there are similar organizations, like the Balochistan Liberation Army and the Balochistan Liberation Front, which are mostly attacking targets within Pakistan and lurking in Iran. And against these Iran has an equally hard time to act.

Though foreign involvement by funding and arms support is undeniable, the problem is deeply rooted in the ethnic fabric of the region, as these terrorist organizations are all connected to the Balūč/Baloch people.

Who are the Baloch people?

There are highly contradicting accounts about the origins of the Baloch people, but they are a group of semi-pastoral tribes speaking a Western Iranian language. Their numbers are relatively small, around 10 million total with roughly two million living in Iran (2% of the population) and 7 million in Pakistan (3% of the population), with smaller groups living in Afghanistan, the Persian Gulf countries, and even West Africa. Though sharing a largely homogenous culture they are also deeply divided, not just by the borders between Iran and Pakistan, but by the many tribes – estimates go up to as much as 150 – and different origins, as many originally not Baloch groups have been incorporated into their tribes.

These numbers would suggest a low importance in these countries, however, in Pakistan’s Balochistan province they are the biggest ethnic group with significant numbers in other provinces as well, while in Iran’s Sīstān and Balūčistān Province, they constitute the majority. And they are almost all Sunnis. Though some groups are Hindus there are practically no Shia Baloch tribes. They also inhabit sparsely populated and hardly accessible areas, especially Iran, and all share a high level of independent mindset a rejection of central authority. In Iran, they also live in the least developed and by far the poorest province.

Given these conditions for long, there was a lack of will to incorporate the Baloch people into a centralized state system and an unspoken self-governance was established. It was much easier to let these regions live by their own rules and customs, as long as they did not jeopardize the unity of the state, or did not constitute a major economic, or security problem. Much easier than starting a long and arduous campaign to break a fiercely independent-minded and divided people in a remote region with little chance of offering social benefits. That sort of non-interference by Tehran and peaceful coexistence was an uneasy, but working approach for long, but in the last two decades was upset by two things. The separatist-terrorist movements, and economic progress and interests in Baloch regions.

Exploiting ethnic tensions both against Iran and Pakistan is nothing new, and even though in Iran these problems soured during the Iraq-Iran war, they eventually calmed down. Yet in Balūčistān since 2010 it flared up once again, largely due to Iran’s problems first with its Gulf neighbors, and recently ever more with Tel Aviv and Washington. But other actors are also interested in inciting these problems.

The other factor that started to upset the former balance was economic progress. In the case of Iran with increasing problems with its neighbors in the Persian Gulf Tehran started to look for alternatives to its main port Bandar ‘Abbās, which is its main gateway to the international markets. But that being in the Gulf is vulnerable in case the Straight of Hormuz is closed down. Iran has a major port outside of the Gulf directly open to the Indian Ocean, Čābahār. This port is deep inside Sīstān and Balūčistān, and as here the infrastructure is way less developed the Iranian state started to invest heavily in roads and transportation, developing the ports and utilities in general.

Also in the last decade, two somewhat competing projects gave special intention to this region. China introduced the Road and Belt Initiative to which the port of Gwadar in Pakistan’s Baluchistan Province is a central point – China has gained almost exclusive concession over it in 2019 -. On the other hand, India has introduced its own economic cooperation initiative to connect Mumbai with Čābahār to make it a key transit point for its trade towards Central Asia. And with the appearance of such massive projects state control and security – at least along the trade and transportation lines – had to be strengthened. But at the same time for any party wishing to undermine stability, these lines became prime targets.

In the same context, it is also important that Baluchistan, especially in Pakistan is rich in minerals, which is further attracting foreign investment and presence. And Iran and Pakistan also got a lot closer economically, which has also stimulated a more intensive interaction at the borders. Just one example of the growing importance of the border region is the Iran-Pakistan gas pipeline project introduced in 2013. Iran has already completed its part in delivering the pipeline despite the security problems, but Pakistan only recently started to speed up construction connecting the border crossing with the port of Gwadar, as the project is due to become operational in 2024. Otherwise, Islamabad would face a $20 billion fine for missing its part of the deal. Though Pakistan claims that the main reason for the delay was that the American sanctions made the project impossible and asked for a waiver from Washington, but with no response. So in order to avoid paying damages Pakistan recently started working on this otherwise very profitable project. And that is just one of the many projects that can connect the two states. However, these projects require more and more involvement in Baluchistan.

Trapped in an eternal contradiction?

Based on all this, what happened this January was not unexpected at all, though unprecedented with bombardments from both sides. In a way, both states are facing the same problem. Separatist rebels in an unwelcoming region, which is better to be left alone, but by now very needed for economic development. The winds of change reached Baluchistan. They both face the same problem, an ethnic group very hard to pacify at a time when attention is needed elsewhere.

That would indicate cooperation, but it is very difficult, as neither side wishes to step up hard and possibly start an uprising. And so they expect steps from the other side. In this regard, Pakistan is surely in a more difficult situation, with a bigger Baloch population in a wider area and a more insatiable hinterland.

However, this setup explains why despite the mutual bombardment and harsh rhetorics they eventually did not commit to war against each other. Simply there is no interest in that by either side. These two states are not enemies at all, though might be in a number of matters uneasy partners. Neither sides have any territorial claims towards the other, nor would they have anything to gain by a war and that is well understood on both sides. Yet, for their own stability, they both have to control their border regions, which is a task hard enough on its own. And so they cannot allow this delicate balance to be stirred up from abroad, even if the reasons are somewhat understandable.

This will keep Baluchistan a hotbed from conflict. And even though a war is not in the interests of either neighbor, the conflict of January 2024 has already shown an unprecedented spillover. And by all indications, this border zone will for the time being remain a source of trouble and a weak spot to be exploited by outsiders.