While most of the Middle Eastern attention now turns to the Persian Gulf amidst possible confrontation between Iran and the US with its Gulf allies, the general Arabic scene seems to be generally quiet. The Emirates are pulling out of Yemen, and there are indications that soon Riyadh will do the same, but the case is still far from over, and the reconstruction of Yemen is still very far away. Algeria and Sudan are still boiling, but for the moment major cataclysm seem to be unlikely in both cases. The Syrian war is still now over and there are many open matters, but the result is known and only the time and the details of Damascus eventually victory over its enemies are in question. Also this week, on the 25 July the 93 years old Tunisian President, Muḥammad al-Bāğī Qā’id as-Sibsī passed away. Which might again cause problems for Tunisia amidst the renewed terror attacks there, but elections were already scheduled for this year. Therefore this might just not cause a major problem after all. All these matters, however, seem to excite the general public much less than the events of the Gulf. Rightly so, since all can feel that the result of this debacle with the failure of the “deal of the century” might just be a game changer in the region. Whether Iran can take the pressure and hold on to its influence, or give concessions and retreat. Within this context, naturally, all bilateral ties are evaluated as a major change in the balance will have its effect on all major regional questions.

One connection, however, seems to be almost completely forgotten and that is between Egypt and Iran. Not like there was much talk about it before, but approximately since mid-2016 it is like the two states have no connections, nor any comments on each other’s dealings even on mutually important matters. Which is puzzling given the importance of both states in the region. Should we keep in mind that the Middle East has four practical regional powers capable of effecting the events on their own, and they are Egypt, Turkey, Israel and Iran.[1] Most of the inner connections between these four are quite well known, though might be controversial, like the Turkish-Israeli or the Turkish-Iranian ties. Yet we hear almost nothing Cairo’s opinion in the current crisis in the Gulf, which is significant considering Egypt is not only a close ally of Saudi and the UAE, but in fact the only major Arabic power.

The relations between these two are in fact very interesting as were they to agree many of the regional problems could be healed. These ties were often troubled, but saw an unprecedented – and unprecedentedly complicated – blossom in 2012-13, only cool down gradually and by now practically die. Much of these details were less known when they happened, and were all seem to forget them, but are import to be remembered if we are to understand the region. Many of the shifts in the relations happened in response to the rapidly changing circumstances since 2011, but many were caused by inner factors isolated from outer reasons. In many ways the two states are very similar, while at the same time fundamentally different. That what makes their connection so unique, and since the circumstances allow us now, the topic of this week.

The oil and the water

By addressing the Egyptian-Iranian relations we deal with one of the most intriguing topics of Middle Eastern relations. Yet at the same time one of the least covered ones. Which is puzzling, since the two states are very similar in a number of ways, and in any case we are talking about two of the most influential regional states. In recent years, however, they seem as they not only have no relations what so ever, but they remarkably refrain to comment on each other, even on mutually crucial matters. That was the case more or less before the so called “Arab Spring”, and that is where relations returned since 2016.

They are very similar states as both of them are heirs of great civilizations, share very similar recent history, have significant armies and economic potential, have hold on two of the most important crossing points in the region, the Straights of Hormuz and the Suez Canal respectively, and have huge influence on the Arab world. Iran is a theocracy built on its 1979 Islamic Revolution, where the armed services, most prominent among them the Pāsdārān and the Basīğ now incorporated into it, play significant political and economical roles. Egypt, at least in theory, is a secular state, but the revolution in 2011 and the counter movement in 2013 play significant roles in the state’s identity and very similarly to Iran the deep state, the army cadres play a significant role in politics and in the economy. Should we not forget that the current president, ‘Abd al-Fattāḥ as-Sīsī was head of the Military Intelligence before Mursī’s presidency, when he became Commander-in-Chief of the Army. After all, he was a Brigadier-General before he became president. Religion is also juncture point, since Egypt might be a secular state formally, but it is home of the Muslim Brotherhood, which is still highly present in the society regardless of the current leadership’s animosity towards it, just like it was the practice before 2011. Therefore, capitalizing on this, as Mursī himself tried, Egypt has the potential to gain influence in the region via one of the most significant Islamic movement in the Middle East. The only two other religious movement in the same capacity are the Wahhābī ideology promoted by Saudi Arabia and the Shia revivalism favored by Iran. Even on historical grounds religious understanding would not be impossible, since Egypt in the Middle Ages was the center of the only Shia Caliphate, the Fatimid Empire. Also in size, population, military power, economic potential and influence in the region they are approximately at the same level. That is also true to the education and technological fields, as Egypt is the biggest Arab state in these, while Iran is one of the fastest growing countries in technological advancement globally. If Cairo and Tehran were to cooperate many of the region’s problems could be healed without outer interference and in a number of economic matters they could help each other. So from a certain angle this would be a match made in heaven.

On the other hand, there are as many contradictions between the two as similarities. Egypt, even if we disregard the secular facade of the state, is a predominantly Sunni state, where the Shia has no presence anymore. The two great religious views most popular in these two states are the complete opposites of each other. The Brotherhood and its affiliates see the Shia as their biggest enemy, for which Iranians usually have a great distrust in the Egyptians. That difference usually fuels animosity not cooperation. In a number of regional issues they are either taking the opposite sides, or there is an almost lethal competition between them. Like Syria for example, was always a vital matter of Egypt, with which it was briefly having a union between 1958 and 1961, but by now is a firm ally of Iran. The Gulf states are also a matter of dispute as Egypt sees them allies and counts on them for economic support, while Iran has constant quarrels with them. In most of the smaller matters there is a constant competition between Egypt and Iran, as both states try to project their influence in the regional states, and therefore their own vision for the region. So despite their many similarities and understandings for each other, they are in fact much better competitors than allies.

Where we came from

Even looking the history of the last century, there is much in common between the two, which should make them understand each other. However, eventually they came to completely different conclusions and in a number of instances pushed their agendas to the other’s expanse.

At the end of the World War I they were both ruled by local monarchies, which had no deep history nor roots in the society and were lightly covered facades of British influence. Britain had a mutual defense pact with Egypt until 1951, and the control of the Suez Canal was a vital interest for the oil shipments, since some two third of European oil import came through Suez. The Pahlavī dynasty in Iran started as a movement to rid the state from Russian-British interference, but after 1941, when the Allied forces facilitated a regime change, Tehran, and especially the new monarch, Moḥammad Reẓā Pahlavī relied heavily on British support against communist encroachment. Not to mention its own parliamentary institutions. Iran was vital for the British oil trade, as the refineries in Ābādān was the main source of English oil. That is the place where BP, originating Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC) was born. In the early ‘50s in both states deep political movements tried to end this British indirect rule, though in different forms. The military coup of 1952 in Egypt ended the monarchy, withdrew from all military accords and reclaimed the Suez. That lead to the English-French-Israeli intervention in 1956 against President ‘Abd an-Nāṣir, which was successful militarily, but failed politically and for some two decades Egypt joint the anti-Western camp. Iran, and this is where the difference started, also witnessed an anti-British movement lead by Prime Minister Moṣaddeq (1952-53). Contrary to the popular vision he did not aim to end the monarchy, but by reducing the duties of the monarch to symbolic roles tried to gain full control of the wealth of the nation, until than in the hands of foreigners. The biggest matter was the oil export and the Ābādān refineries, for which Iran was willing to suffer complete boycott, and the matter was ended in 1953 with an MI6-CIA instigated coup. That removed Moṣaddeq from power and stabilized the rule of Moḥammad Reẓā, who in return not only allowed further British economic presence – though in a much reduced fashion -, but by firm British and American support became a bulwark of Western presence in the region. So what Egypt experienced in its independence struggle against the British in the form of direct military confrontation, and won in it, Iran witnessed in in the form economic warfare and secret service operations and failed. While Egypt became a major concern for the West from the ‘50s, Iran was transformed into “America’s policeman” in the region.

In time their positions changed, but ironically they stayed at the opposite end of the table. In the 1979 Islamic Revolution Iran permanently broke with the West and since then propagate an idea very similar to what ‘Abd an-Naṣir wished for. Namely that the countries of the region should rid themselves from outer interference and should rely on their own capabilities. Though since the the death of Homeīnī Iran gave up its quest for the export of the revolution, at least officially, it still promotes regional cooperation and self reliance, which proved to be a much more effective tool in foreign policy. Egypt on the other hand chose a completely diagonal path. Under President Sādāt (1970-81) it gradually broke with its Soviet-Leftist orientation and by signing a peace treaty with Israel started to bond with America. The break with the regional self-reliance doctrine was most visible, when Egypt took this path even by suffering expulsion from the Arab League. To which the return came in the ‘80s to the expanse of Iran. It also did not help the relations that quite when Iran broke all connections with Israel and gave the former Israeli embassy to the Palestinians Egypt made peace with it, and that Sādāt gave refuge to the shah, who died and was buried in Cairo.

When the Iraq-Iran war started and the initial Iraqi thrust failed to bring about the collapse of the Islamic Republic, the prolonged war made Iraq to look for more support the Gulf could offer financially. That is the time, already under President Mubārak (1981-2011) – a much weaker successor of Sādāt -, when Egypt gradually made its way back to the Arab world and got readmitted into the Arab League in 1989. By then, with huge financial support already pouring in from the Gulf and from the US, Egypt completely took a pro-Western position similar to the Gulf states, and as an intermediary between the Arab world and Israel. From such a stance, naturally, Cairo regularly voiced the same concerns towards Iran as the Gulf monarchies as Mubārak himself many times accused Tehran with attempts to interfere with its domestic affairs. Cairo, just like the GCC members, complained that Iran interferes in Arab inner affairs, though from Egyptian point of view this meant that Iran was expanding its influence to Cairo’s expanse in Palestine, Syrian, Lebanon, and even in the Arabic Peninsula. So, much of the concerns of Egypt should be understood in this light, even if their words mirror the Saudi-Emirati-Bahrain statements.

The honeymoon years

The two state, just like now, behaved as cold adversaries having almost no relations with each other since 1979 and tried hard not to take the other into consideration. The lack of open confrontations was mostly due to the fact that Tehran recognized it cannot influence Egypt and hoped for better times, when things might change. And that change indeed came, bringing about the most promising times in the relations, thought by mostly highly misread expectations.

When the so called “Arab Spring” started by many it was read as a genuine Islamic revivalist movement. Though by now we now that in Egypt, just like in practically all states, this movement was instigated from abroad and the Brotherhood served as a blunt instrument, in the early months of 2011 this revivalist idea was widely believed. By a strange coincidence, it was especially popular in Iran. Not by the majority of the political and deep state elite, which viewed the matter with great concern, but by the infamous president at that time, Maḥmūd Aḥmadīnežād (2005-2013).

He came from a very distinct segment of the Iranian political class. One that is highly patriotic, very confrontational with the West, and in religious terms one of the most fervent disciples scholars like Ayatollah Moḥammad-Taqī Meṣbāḥ Yazdī, who has little regard to this world, since he is convinced that the return of the Hidden Imam is imminent. Therefore religious discipline should be upheld with the upmost rigor and that is the only thing that matters. This cluster, thought curiously most of Aḥmadīnežād’s closest advisors were pragmatists, not religious ideologists, made their credit as being the first generation of the Revolution having achieved everything after it took place, and resonated well in the rural population. At least initially. Aḥmadīnežād proved to be way more confrontational than the political class could take it, way more conservative as the population could take, and generally a very poor economical caretaker. All these factors contributed to massive disillusionment in Iran. Not only in him, but in the whole establishment after the the controversial elections in 2009, when the elite held him in place only to save the image of the state. But while the establishment viewed Aḥmadīnežād as a scandal and safety hazard, therefore a replacement should be looked for immediately, he became even more sure of himself to conduct his own policies apart from other centers of power and started to build up his own power base. This all should be held in mind when we assess how the Iranian state officially reacted to the Arab Spring.

While most political power centers in Iran were suspicious about it, Aḥmadīnežād saw a great opportunity in the Arab Spring. Especially that it started in states, which are in the pro-Western camp, like Tunisia and Egypt. He viewed these “revolutions” as repetitions of Iran’s own, and these will result in Islamic republics. That is why in spite of the Brotherhood’s great hatred for the Shia and now gaining control in a number of states, Aḥmadīnežād openly welcomed these changes in a number of instances. In certain instances of course this was viewed favorably by the elite, like in Bahrain or Yemen, but those with more vision saw the wave might soon reach friendly states like Syria, Lebanon, or Iraq, where such enthusiasm will cause trouble. Also the now emerging powers might be Islamic in name, but very anti-Iran and anti-Shia in nature. Therefore they prompted caution. But Aḥmadīnežād, by than much reassured of himself, would have none of it, and endeavored in one of his most controversial, though intriguing quests, a rapprochement with Egypt.

That was in fact not new, as in 2007 Aḥmadīnežād proposed to restore full diplomatic connections with Egypt and close all pending matters. That was mildly welcomed in Cairo, but nothing came of it. So it was natural that the Iranian President welcomed the change and hoped to capitalize on it. Especially when with Mursī an openly Islamic movement came to power, who soon stretched out to Iran. By official invitation from Tehran, Mursī visited Iran on 28 August 2012, being the first Egyptian official to that after 33 years. In that trip Mursī affirmed his intention to build strong ties with Iran, and that cooperation between the two states can solve all regional disputes, Syria being at the top of the agenda. On 5 February 2013 Aḥmadīnežād returned the favor by visiting Cairo, being the first Iranian state official since the revolution to go to Egypt in an official visit. Though Mursī warmly welcomed him as potential friend, the next day the Iranian President already experience how difficult his idea is, when he ran into a scandalous press conference with the sheik of the Azhar Mosque. While it was an important approach for Aḥmadīnežād, it was even more important for Mursī as he viewed Iran a potential friend a more reliable supporter. He feared repercussions from the West for being Islamist, and not trusting his own military elite, most of them educated in the US.

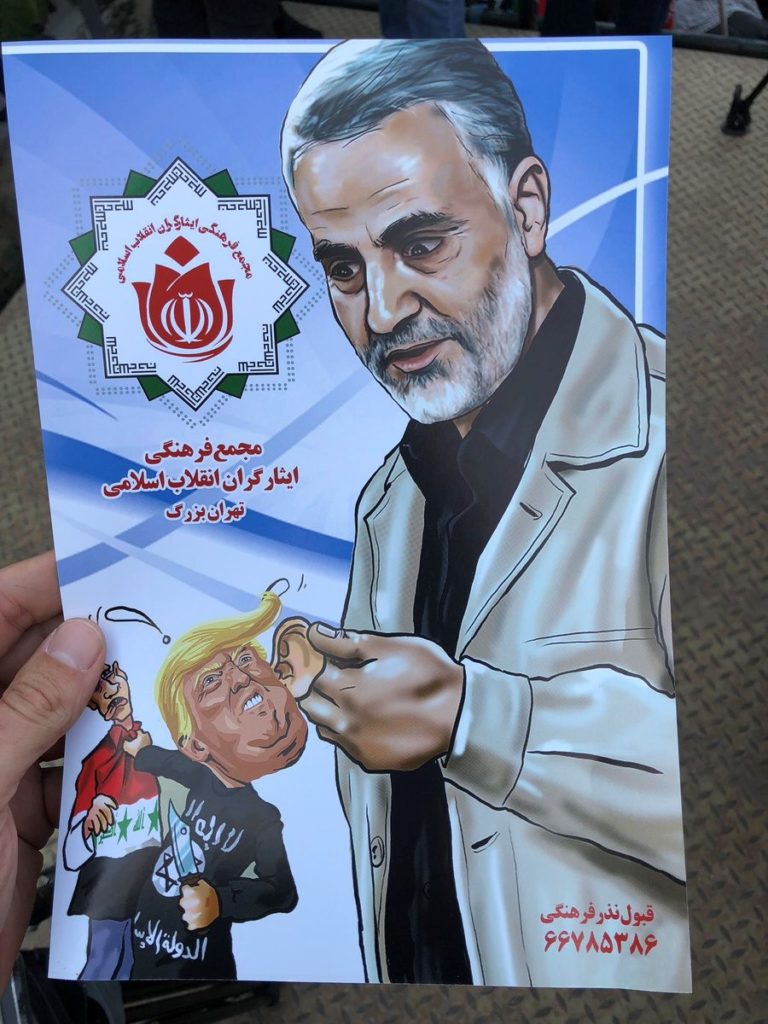

Reports have it that even before the official visit Mursī asked for support to create the Brotherhood’s own security apparatus resembling the Pāsdārān and the Basīğ. To that aim at the end of December 2012 Qāsem Soleymānī was sent to Cairo for a two days visit, where he met with ‘Iṣṣām al-Ḥaddād, Mursī’s foreign affairs advisor and practical head of intelligence. Interestingly at that time, between August 2012 and March 2014 the Minister of Defense and Commander-in-Chief of the Egyptian Armed forces was none other, than ‘Abd al-Fattāḥ as-Sīsī, who just before that served as the head Military Intelligence. Meaning that it is

highly unlikely these negotiations took place without his knowledge, even if he did not take part it them. On the Iranian side, however, the person in question is significant as Qāsem Soleymānī is a living legend, and not only in Iran. He was already a hero in the war against Iraq, after which in the late 1990s became head of the Pāsdārān’s elite Qods (Jerusalem) Forces, which’s main task is to provide military assistance by training and special operations to allies abroad. Soleymānī himself became a legend appearing regularly in Syria and in Iraq fighting against Dā‘iš, but also regularly airing political opinions, mostly against American threats. If he was sent to Cairo to assist Mursī and the Brotherhood, though him being a very far-sighted and tactical person, surely did not approve the mission, this was not a gesture but a very serious initiative. The seriousness of this attempt by Mursī is further reaffirmed by the fact that almost at the same time, early January 2013 Qatari Commander-in-Chief Aḥmad ibn Nāṣir ibn Ğāsim also visited Cairo without meeting with any Egyptian military commander.

Regardless all apparent contradictions and technical problems this rapprochement was not confined to secret dealings and groundbreaking official visits, but Mursī in many interviews insisted that he sees a potential ally in Iran and in a number of cases, like in Syria, he counts on Tehran’s support. Given that we were just after the the hardest time for the Syrian state against the foreign sponsored terror war, in which the Mursī government was heavily involved, it is puzzling what was the rationale for that somewhat diluted approach. The main objectives were contradictory as Mursī and the Brotherhood needed to push for even more like minded governments in the region, and for that Syria was essential, while Iran needed to stop the wave before it reached Tehran, again Syria

being the key bastion. Though at the same time Mursī needed funds and support, even if from Iran, since no one else was willing to give it to him apart from Qatar. However Aḥmadīnežād wanted to expand this relation he just could not deliver it, as in his last year or two he was practically sidelined by Hāmeneī, exactly for his blunders and for his misjudgment on the whole current.

While this two years period might seem brief and by now insignificant it was groundbreaking as the two regional powers tried for the first time to mend fences. But this honeymoon ended in mid-2013, as in both countries major changes occurred. In Iran Aḥmadīnežād was replaced by a skillful technocrat, Ḥasan Rōḥānī, while Mursī was ousted by a coup lead by as-Sīsī.

Please, stay with me!

That should have ended the briefly enjoyed rapprochement, yet Iran took lengthy steps to keep and even improve the already started initiative. And that went on almost until the end of 2017. Between 2013 and 2016 the official ties cooled down, but the deep-state connections in fact increased for a number of reasons. The new Egyptian leadership tried to reverse almost everything Mursī did, and ironically that as well helped the relations. By getting rid of Mursī’s biggest supporters, Qatar, Turkey and the Brotherhood, Cairo was hitting hard forces which were causing trouble for Iran’s allies in Syria, Lebanon and Iraq. There was a genuine understanding between the two truly fighting Dā‘iš and its affiliates in the region. Though officially they could not praise each other, since as-Sīsī was the result of a shah-like military coup against the democratically elected Islamist president, ironically the need was bigger than ever to cooperate and it worked. There were clear signs of on-the-ground cooperation both from 2014, and 2015, through even at that year as-Sīsī denied not only any connection, but even possibility to restore diplomatic connections any time soon. That, however, was probably only a facade as he needed continued support from the UAE and Saudi Arabia.

2016, even 2017 actually brought the sides together for a number of reasons. Syria was already getting over the worse and Egypt felt that would be an opportune time to lift a hand. So Cairo discreetly mended fences with Syria and even gave limited military assistance, while the intelligence cooperation started to flourish. For that approach to work Egypt needed Iranian blessing as well. Yemen was for some time a collusion point as Egypt supported the Saudi lead war, and Iran strongly opposed it. But soon enough cracks started to appear between Cairo and Riyadh, which by mid-2016 became a major rift, best manifested in the dispute over the islands in the Straits of Tiran. Iran sensed the opportunity to finally distance Cairo from the Gulf, and in October 2016 Tehran offered to supply Egypt with Iranian oil. The case by that time was handled by Deputy Foreign Minister Ḥosseyn Amīr ‘Abdollahiyān, one of the best example of the Rōḥānī administration’s professional cadres, who worked hard to keep the Cairo-Tehran channels open since 2014. That was the same time when Cairo’s approach with Syria was at its zenith, Iran was coming out of the sanctions thanks to the JCPOA – so it was not a necessity to help Egypt economically -, and even on the ongoing Syria peace talks in Lausanne Iran demanded Egypt’s presence as well. Even more, Tehran set Egypt’s presence as a precondition for its own partaking.

These approaches were unanswered by Cairo, at least officially, and while Tehran kept trying, after 2017, when Egypt and a number of Gulf states started their Cold War against Qatar it all stopped. The reason is probably not the warming Iranian-Qatari relations, but the fact that such a move by Cairo clearly signaled that it solved its matters with Riyadh and there is no space for Tehran here anymore.

The matching interests

In a number of points it is important to remember the crossing interest, because that answers us why the two states kept on trying to be friends even after 2013 and why it all failed. Yemen was such a point, but Egypt stepped out relatively soon, remembering well from the ‘60s what it is to fight there. While a possible Iranian bridgehead in not favorable, it is much better than the Turkish and Qatari possession around the same area. At the end, Egypt doesn’t really care who wins there. Syria was important for Cairo to cause pain to Saudi and Turkey at that time, having difficulties with both, and intelligence cooperation was vital for Egypt as fanatics started to pour back to the country. Now giving some support to Damascus could have sweetened the deal, but Egypt soon realized the it can not carve out influence for itself there in the expanse the already present forces. So why to bother? Iraq means a similar idea for Egypt. By now the Egyptian President gave up all non-emergency foreign matters, partially due to the fact that he stabilized his post and Western support started to pour in again, and partially because the economy is still not doing well, and the insurgency in the Sinai is still raging on.

From the Iranian point of view right before the JCPOA, and after Trump’s victory when it was clear it will be abrogated Iran needed a stable and large-scale trade partner. Securing oil sales could have meant a return for the European markets as well. A number of strategic affairs also promoted consolidation. Distancing Egypt from Saudi, both in Yemen and in general was perfect for intimidation. Which worked somewhat in 2016, only to as-Sīsī’s favor in the long run. Also if Egypt took Syria’s stance in the Arab world that would have meant Damascus’ reentry to the Arab League and some sort of guarantees to end the war there. That was critical in 2014, before the Russian intervention. A number of matters, however, simply outdated these aspects. Egypt could deliver nothing and was clearly playing to gain more finance from the Gulf. Therefore its detachment from the Riyadh-Abū Zabī axis is an illusion. Turkey showed perfect willingness of cooperation, even after the JCPOA collapsed, therefore a steady trade partner is secured. And the growing trade partnership and cooperation in mutual security matters made Turkey a valuable asset. Given the animosity between Ankara and Cairo, Egypt simply doesn’t worth as much as Turkey. The Russian intervention and the Syrian Army’s victories in recent years rendered all possible Egyptian help unnecessary, even unwelcome by Damascus.

All these factors, though Tehran truly put a lot of effort into it, eventually killed the renewed alliance between the two states.

The potential and the future

There is something truly ironic that the two very leader, who broke the ice between the two countries are by now permanently out of the picture. On 17 July 2019 Mursī died in prison, while Aḥmadīnežād became a political outcast in Iran, who fell as far to even renounce the 1979 Revolution as a British plot, regardless he took part in it. As if faith had it this way, that ideology was buried under the rationale of state interests.

For any foreseeable future there seems to be no hope for renewed Iranian-Egyptian cooperation. The current status is convenient for both, while changing it would take way too much effort. However, now in both sides there are people, who have firsthand experience with the others, which can cause mistrust, but just as much can be built on it.

This brief encounter after such a long isolation from each other shows the possibility for an understanding, while the sad faith of the two late presidents the limits of such an initiative. Which is quite unfortunate given, religious and ideological differences aside, there is great potential in the cooperation both strategically and economically.

For the time being, as Rōḥānī in his remaining brief three years and much bigger problems at hand rapprochement seems unlikely. But with a likeminded successor, with diminishing Saudi and possibly American influence in the region, and the changes enforced by China’s economic appearance, there might just be a a fertile ground for Cairo and Tehran. Especially that such an understanding would be much welcomed in the region after the troublesome years of Gulf meddling.

[1] One might add Algeria, but given its limited ambitions outside its neighborhood and its inner problems now Algiers is not on the same level. While Saudi Arabia might have immense economic power and a standing army, but its power projecting capacity have just died inside Yemen.