For almost two years now Lebanon is going through one of its deepest political and economic crises. This is remarkable, as the current crisis even overshadows the bloody chaos of the Lebanese civil war. The civil war erupting in the ‘70s was undoubtedly bloodier and more confusing, but at that time Lebanon was surrounded by relatively strong neighbors, who along with their great power supporters were all trying to wrest their power here and support their local allies.

This time, however, the whole region is in turmoil. Syria is just coming out of the long bloody war launched against it, and even Israel is experiencing internal conflict and setbacks in the region.

Lebanon is once again a key spot on the regional chessboard. Yet much of its current troubles are because of the unsolved legacy of the civil war, as many sides still have score to settle with their former foes. Within this deep crisis, which once again saw regional and international attempts to change the equation, recently Lebanon started to see some light at the end of the tunnel. Investigations against the Riyāḍ Salāma, formerly untouchable head of the Lebanese Bank is under investigations and is about to be removed. A new government was finally formed under Nāğīb Mīqātī, who for the moment enjoys the support of the biggest power blocks. And two separate regional initiatives started to ease the economic and energy crisis Lebanon experiences, one by Iran, and another by Egypt, Jordan and Iraq, while Syria plays a vital part in both projects.

This rearrangement, however, as it is only natural in this deeply divided country, left some deeply unsatisfied. This volatile atmosphere served as the background for the recent massacre in aṭ-Ṭayūna neighborhood on 14 October, which left at least 7 people dead in a political protest. A scene reminiscent of the civil war days.

The culprits and the masterminds are all relatively known. But given the circumstances this event might tear open the old wounds of the civil war and ignite a new one. Thus ripping Lebanon apart once again. So far the situation is under control, but the frustration is growing. And the explosive box of the Middle East can blow up any second, so close to solution.

A volatile atmosphere

When the current deep political and economic crisis broke out after the resignation of Prime Minister Sa‘ad al-Ḥarīrī we dealt with the circumstances. After the utter meltdown of the complete Lebanese economic and political structure set up at the end of the civil war and immediately after it logic would have dictated a rapid reconfiguration and mending the wounds of the country. But it wouldn’t have been the Middle East if all went easily. A bitter power struggle started on one hand by certain forces to truly bring change about, while on the other the losing sides doing their best to bring down the appointed government under Ḥassān Diāb. Which indeed happened in August 2020. The immediate cause was the tragic explosion in Beirut’s main port, the biggest ever non-nuclear explosion in an inhabited area. If nothing else, this shocking tragedy showed have prompted all Lebanese political sides to finally bury the hatchet and work on putting the state in order, yet once again political rational prevailed and the bickering continued. Resulting an even deeper downward spiral.

The devastation of Beirut port did not reset the political equation, only opened a new chapter of the political struggle and gave a new reason for the internal conflict, as all sides tried their best to put the blame on the others and offer a solution on for the growing crisis to their own likings.

The underlying conflict of the whole problem was the shifting balance both in the region, and within Lebanon. As the war in Syria is closing to its end with the Syrian leadership surviving the war war launched against it, and while Iran also managed to overcome the effects of Trump’s policies balance inevitably shifted towards the Axis of Resistance. Which within Lebanon meant the developments favoring the biggest Shia party, Ḥizb Allah. While Ḥizb Allah was cautious not to exploit the situation, being mindful of the internal sensitivities, change was felt and all power blocks tried to prevent the Shia party becoming all too powerful. Bringing down the coalition government in 2019 and trying to form a new one without Ḥizb Allah was desperate attempt by Sa‘ad al-Ḥarīrī to reposition himself, and the gamble eventually failed. All later events can be understood within the frameworks of this underlying theme, with two other features being important. Political factions were not only deeply divided along the pro-West versus pro-Iran and pro-Syria blocks, but some, like the biggest Christian party, the Free Patriotic Movement of President ‘Awn tried to keep the ship afloat. Thus accepting any development, which offers solution. Yet this caused quite unstable realities. On the other hand within the deep sectarian division, all parties representing the political fiefdom of a respective strongmen tried to pose themselves as the most dominant force of their religious background. A struggle, within the war, which makes the whole constellation confusing and unpredictable.

In such an atmosphere, where the political elite is without responsibility for the country and all have an eye for growing their influence any event, even the mildest is looked upon not by facts, but through the lenses of distrust and old scores to settle. And provocations grew steadily in the last two years. The protests following Sa‘ad al-Ḥarīrī’s resignation witnessed atrocities against Ḥizb Allah and Free Patriotic Movement centers, but that eventually did not cause civil war. Violence already broke out in August 2021, when a funerary process was fired upon (Magyar) in the mostly Shia inhabited southern part of Beirut. That time Sunni radicals were behind the attack and the Lebanese army managed to contain the situation, while Ḥizb Allah refrained from hasty reactions.

When recently the conditions around Lebanon started to improve, as both Iran and Egypt agreed to transport energy resources to the country and a government was formed the prospects were promising. But as both projects had major Syrian involvement in it, the outlook inevitably showed that Ḥizb Allah despite all pressures managed to solve what the whole political establishment without could not.

Here we wish to point out that by this we don’t aim to suggest that Ḥizb Allah, or any major Lebanese political formation is clearly better than the other. All these parties are deeply responsible, as they have been in last four decades, for the political setup. But there is an appearance, and outlook, in which Ḥizb Allah and its current (temporal?) allies are winning the struggle, leaving their toughest opponent on the losing side.

The massacre in aṭ-Ṭayūna

Within this sensitive atmosphere a new atrocity happened last week, which tore open all slowly healing wounds. Protesters gathering in front of the Justice Palace the aṭ-Ṭayūna roundabout in downtown Beirut were fired upon leaving at least 7 people dead and tens wounded. It was immediately clear that snipers opened indiscriminate fire upon them and the army was rapidly deployed, but even after the culprits were arrested, it was less clear who stood behind it. It was all the more confusing that in Lebanon it is only normal for many people to have arms, and some opened fire towards the suspected snipers even before the army intervened. Leaving a confusing scene, where it was not indisputable who shot whom, and whether the protest was peaceful as they claimed, or was armed. Because if the latter is true, blame can go far who is truly responsible for the outbreak of violence. And no doubt, the old game of mutual blaming started once again.

The footage was also circulated heavily on social media for its somewhat comic nature.

(Source: Facebook)

By now most fingers point toward the Lebanese Forces Party led by Samīr Ğa‘ğa‘, as allegedly some of those detained admitted to belong to this party’s militia. But even if their guilt was to be proven, eventually in Lebanon nothing is entirely clear and nothing comes clean of sectarian sensitivities. And whoever was the true mastermind behind the attack, he surely counted on this. Logically suggesting that the main goal was to set the stage for yet another sectarian civil war.

But how events escalated to this? As we saw the conditions in Lebanon these days are all set for hell to break loose. The immediate events before the massacre all came in the framework of the previously explained sensitive mindset.

After the explosion in Beirut port almost all policies leaders demanded a swift and decisive investigation, also vowing unconditional support for the inquiry. Once again politics intervened and the process went along excruciatingly slow. The first judge tasked with the investigation was the experienced Fādī Ṣawwān, a Maronite Christian with a good reputation. He faced growing difficulties, however, after he charged to former ministers, Ġāzī Za‘ytar and ‘Alī Ḥasan Halīl for negligence leading to the disaster. Given both ministers are Shia from the Amal Movement, an ally of Ḥizb Allah, no leading politicians of other parties were charged and Ṣawwān himself being a Christian all played a role in the mounting criticism, until on 18 February 2021 he was removed from the case. Fury grew for many reasons. It was clear that appointing a new judge will be difficult and highly politicized, and will just further delay the process. Also because it was clear that political influence once again play a major role in the inquiry, putting serious doubt that this time it would not be a political outcome. Two days later yet another judge, Ṭāriq Bīṭār was appointed, a Christian from the north, from area overwhelmingly supporting al-Ḥarīrī’s Future Movement.

Bīṭār largely followed in the footsteps of his predecessor, requesting the detention of Prime Minister at the time of the explosion Ḥassān Diāb – another ally of Ḥizb Allah – and upholding the case against the two formerly accused ministers, while largely disregarding other leading politicians possibly implicated in the disaster.

Lately investigations entered into new rounds. This triggered the fury of Ḥizb Allah for very understandable reasons. It could be felt – or at least could be argued for – that the inquiry is indeed taking a political angle. Though Ḥizb Allah was not directly targeted, the inquiry was taking an direction against its allies, putting the Shia party into a sensitive position. It either disregards the developments and the complaints of the ministers jeopardizing the trust between itself and its allies, or moves in, once again risking the appearance that the party is pressuring the process for its own liking.

In this context came the speech of Ḥizb Allah’s Secretary General Ḥasan Naṣr Allah on 11 October labeled “Victory is with patience”. In this Naṣr Allah vehemently criticized the whole process still demanding justice, but claiming that it took a highly politicized course. Thus he was not demanding the cessation of the inquiry, but demanding a more fair – or more favorable?! – approach. The result was that a protest was organized to 14 October in front of the Justice Palace, to demand the less politicized inquiry.

Regardless of the reasons two things were clear. The aim for the protest was indeed to put pressure. But given the sensitive nature of the matter, no force was planned to be used, knowing full well that any armed action will be used against Ḥizb Allah.

The protest turned out to be relatively big, when suddenly live fire was opened in the protesters. Confusion and rapid violence broke out even against the army, blaming it for letting the massacre happening. It is indeed hard to see clear when exactly fire was used against the snipers, and whether those who shot at them were present in protest, or only appeared in result, as the area has a significant Shia population.

Two distinctly different approach started to manifest. On the one hand it was presented by sides mostly close to Ḥizb Allah that peaceful protesters took to the streets to protest lawfully against a political witch-hunt, when they were shot at by snipers. By this version the aim was simple sectarian hatred and to provoke aggression, eventually blaming Ḥizb Allah for renewed violence. Maryam Farḥat, an innocent bystander local resident, a mother of 5 children waiting her children to come home from school became the symbol of this version, who was got killed, thought she did not event take part in the protest. And she was also Shia.

The other version mostly focuses on the allegations that the protest was not even peaceful, but there were many armed men in the square. A possibility not at all unlikely. Thus critics of Ḥizb Allah usually point that it was the this party, which took arms to the streets and underlined that all other victims except one were young men, all being active – possibly armed – members of Ḥizb Allah and the Amal Movement. Which is true, yet this script oversteps the role of the snipers, and only raises doubts about the identity of the shooters. Much rather the appearance is given that Ḥizb Allah fighters attacked, or simply “clashed” with groups of the largely Christian Lebanese Forces.

Given the confusion and the massively politicized nature of the whole Lebanese reality it is hard to know the exact sequence of events. And probably the whole truth will never be known as more and more theories and accusations will flood the media.

However, it should be pointed out that it is largely uncontested that snipers opened fire on protesters. Also, Ḥizb Allah had little reason to start confrontation. Overall matters are proceeding for its favor and the last thing it needs is to be entangled in a bloody internal conflict. It is also becoming more clear and uncontested so far that the snipers belonged to the Lebanese Forces, a political party led by Samīr Ğa‘ğa‘. A person with a brutal reputation, who was once an ally for current President Mīšāl ‘Awn, but always a staunch adversary of the Shia and Ḥizb Allah. A person, whose political career was already coming to its end in 2019, when Sa‘ad al-Ḥarīrī stepped down, and since then his fortune only turned worse.

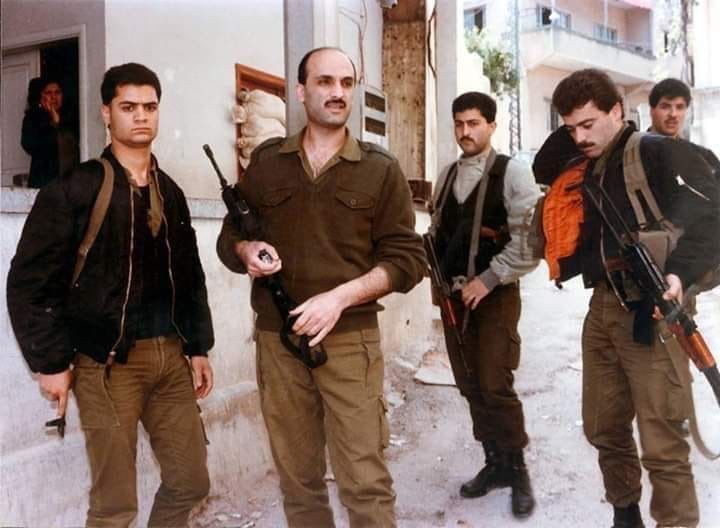

Who is Samīr Ğa‘ğa‘?

Samīr Ğa‘ğa‘ is one the five old faces of the Lebanese civil war, who managed to stay strong on the political scene even after the war ended. The others being Ḥasan Naṣr Allah, leader of Ḥizb Allah. Nabīh Barrī from the Amal Movement, who largely lost his former influence, as once the Amal was the strongest representative of the Lebanese Shia, but since 2000 steadily became the junior ally of Ḥizb Allah. Current President Mīšāl ‘Awn, who had to flee the county after the war, only able to come home after 2005. And at last Walīd Ğumblāṭ, the leader of the biggest Druze party, who changed sides more than anyone else. Ğa‘ğa‘, however, is by far the most extreme amongst them.

None of these names have a clear reputation, but none is so embroidered with blood and violence, as the Ğa‘ğa‘. After all, he was the only protagonist of the civil war, who was but into jail for long years after the civil war, despite the general amnesty at the end.

Ğa‘ğa‘, who was born in Beirut to a middle class Maronite Christian family was once the right-hand man of the al-Ğamayyil family, which until the civil war was the practical leader of the Lebanese Maronite. And thus Lebanon itself to a large extent. He became a useful and utterly brutal enforcer, a typical tough man. He managed to resourcefully organize the Christian militias and became a vital asset in hands of the much more tactical and socially acceptable al-Ğamayyil clan.

When the civil war broke out, he was one of the founding members Christian Maronite militias and their umbrella, the Lebanese Forces in which the infamous Phalange was the most dominant force. His most direct associate and practical boss was the young leader of the clan, Bašīr al-Ğamayyil, and thus Ğa‘ğa‘ became one of the most feared face of the war. In 1982, however, shortly after his election victory and turning his back on his former Israeli allies Bašīr al-Ğamayyil was assassinated and thus Ğa‘ğa‘ was left without a boss. Bašīr’s brother, Amīn took over all his posts and also became Lebanon’s President, but lacked any charisma. Soon all what was held together by Bašīr broke to separate parts. The Phalange – known in Arabic as Katā’ib – was weakened by groups splintering out, while the Lebanese Forces also slowly broke to separate units under the former commanders.

Ğa‘ğa‘ was just one of these commanders, not even the most prominent in 1982, but by 1986 with careful maneuvering he bested all his rivals and became the head of the Lebanese Forces. With meticulous work he managed to reform and significantly strengthen his forces making them possibly the most dominant Christian armed force. In his Christian heartland he created a semi-state with social services and local administration, very similar to that of Ḥizb Allah in the south.

Ğa‘ğa‘ remained an adamant opponent of the Syrian presence in Lebanon and the Palestinian groups and Ḥizb Allah, and for a while his fortunes were promising. For a brief period he supported Mīšāl ‘Awn’s attempt to outs the Syrian forces from Lebanon. In 1990, however, the Syrians forced ‘Awn out of the country and Ğa‘ğa‘ remained the strongest Christian player on the scene. The same year the civil war practically ended with the aṭ-Ṭā’if Agreement, which granted amnesty to all, who committed atrocities against in the struggle. Ğa‘ğa‘ benefitted from this, though he was an opponent of the agreement. The war itself, however, was far from over, as there was still Israeli occupation in much of the country and Syria was also still present. Thus Ğa‘ğa‘ was becoming more of an obstacle for a general settlement. His fortunes were running out, as by 1992 he would purged from the Phalage, and he formed his own political party. The still ongoing war, by this time against the Israeli occupation left Ḥizb Allah more on the winning side, and Ğa‘ğa‘ was pressured to leave the country, which he refused.

After a still unclear bomb attack in 1994 leaving 9 people dead a purge started against him and his followers. His party was banned, his direct lieutenants were arrested, and eventually that year he also got detained and trialed. In a highly politicized trial he was acquitted from the main bomb attack charge, but was found guilty in a number of assassination attempt made after 1990, thus not falling under the protection of the previous amnesty. He spent the next 11 years in solitary confinement, becoming the only protagonist of the civil war to end up prison. That’s how important and dangerous he still was.

His fortunes changed once again in 2005, when after a political assassination and major protests against the Syrian presence the Syrian forces left Lebanon and the political landscape was completely reformed. Ğa‘ğa‘ was released, his Lebanese Forces party became official once again, and it became the most dominant Christian force in the so called 14 March Alliance overwhelmingly winning the 2005 elections. Though at the time of the elections he was still in prison.

In the following years he managed to largely rebuild his former influence and formed close ties with France and the United States, though later documents proved that he also became a protégée of Saudi Arabia. He benefitted from the war in Syria since 2011 and in 2014 he was one of the possible candidates for Lebanese presidency, a post must be filled by Maronite Christians.

Yet with the election of Mīšāl ‘Awn as president in 2016, as ‘Awn predominantly Christian Free Patriotic Movement was gaining favor, and the balance once again shifted towards the pro-Syrian block started to end up in the losing side once again. Allied with al-Ḥarīrī and Ğumblāṭ had a big role in bringing down the coalition government on 2019 in a desperate attempt to change the equation.

As we saw this attempt eventually failed. Today the prospects of Ğa‘ğa‘ are grim. He became more of mercenary by now, with still considerable militant backing, but largely dependent on foregoing donors. But these donors have diminishing interest on prolonging the war on Syria and its allies in Lebanon any further. Saudi Arabia is on a rapprochement with Iran, France is losing its former influence and the US is repositioning itself in the region. All these developments are very bad news for Ğa‘ğa‘ and the Lebanese Forces. Unless a new civil war breaks out, in which he can be a dominant player once again.

On the brink of a new civil war

There is little doubt that the real intention behind the events of aṭ-Ṭayūna was to provoke civil unrest. The Lebanese Forces fit this role, but it should be noted that Ğa‘ğa‘ is still more of an enforcer than a shrewd tactician in such a level. Thus suggesting much bigger forces trying to reset the Lebanese equation. And in this attempt the Lebanese Forces is more of an asset than a real mastermind.

The situation is tense and there is a very real possibly for a new civil war. It should be kept in mind that overall frustration with the whole political establishment is high and living conditions are desperate.

Given the circumstances that last thing Ḥizb Allah wants is an internal war breaking out. Right now the developments are favorable for the Shia party and they don’t want to be bogged down in a bloody war, which will once again attract foreign meddling. That is why Ḥasan Nasr Allah’s last speech on 19 October was very restrained. He blamed the Lebanese Forces for the massacre, but called for moderation and said that the Christians are victims, in a way hostages of Ğa‘ğa‘. Knowing well that the alternative is Ḥizb Allah current ally, President ‘Awn’s party.

Overall an escalation only benefits certain now marginalizing political blocks, and would do great harm not only to the country, but the whole region. With Lebanon flaring up the Syrian crisis will be prolonged and the a general regional settlement becomes complicated. The following weeks will tell if further bloodshed can be prevented.