2024 has an unusually high number of elections around the world, including the American presidential elections, the European Parliament elections, or the Russian presidential elections, just to name a few.

Iran was originally not about to appear on this list specifically interesting with only a mildly existing parliamentary one – with a noticeably low turnout -, but after the tragic death of President Ebrāhīm Ra’īsī became a rare example of having not one, but two major elections. Yet even this, judging by the last presidential campaign only three years ago, seemed to attract little excitement, even in Iran. The race seemed to be set, with a old trusted conservative clerk of the establishment put in charge for the time being, until the next figure is found.

After the Guardian Council from among the dozens of applicants with some noticeably big names both from the Conservative and the Reformist camp approved only 6, and just one smaller weight reformist, the race seemed set. Even more so after days before the first round of the elections on 28 June two candidates stepped back for the Conservatives.

And so it happened that after the prognoses indicated an uninteresting elections, on 28 June it all suddenly turned very exciting. Because there were surprises on many ways. And right before the second round held on 5 July, it seems very possible that Iran would once again choose a reformist president, and after almost twenty years, once again a non-clerical one.

But is that really possible? And what would that bring?

The surprise of 28 June?

Judging by the usual trend of the Iranian political swing between Conservatives and Reformists while after the two terms of mildly reformist President Rōḥānī in 2021 Ra’īsī represented the conservative camp, it seemed almost for certain that whoever follows him, will be from the same block. That was further underlined by two telling signs.

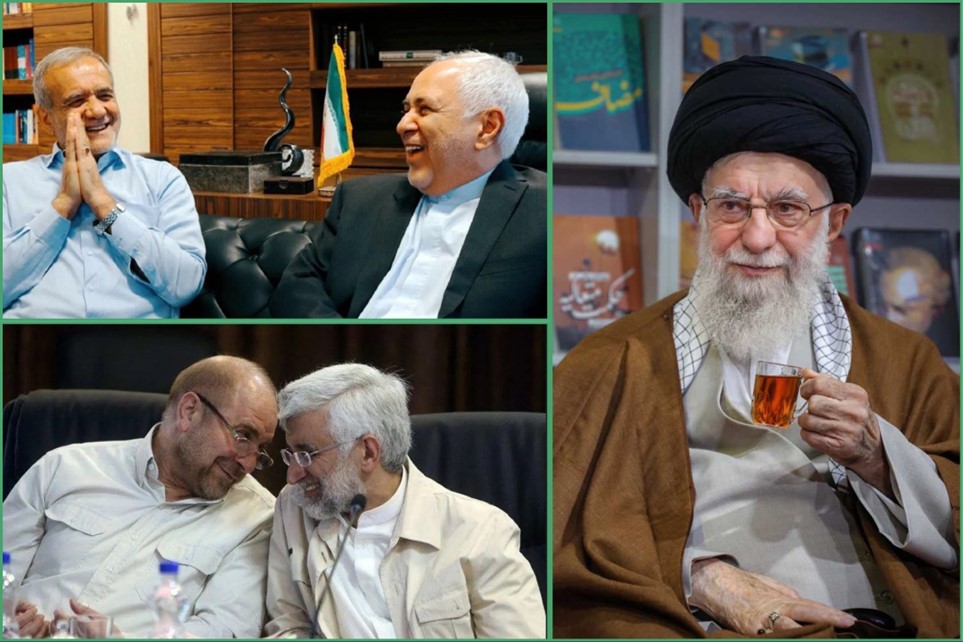

The legislative elections and those of the Council of Experts held shortly before the death of President Ra’īsī both showed a landslide victory for the conservatives, partially because the reformist groups started to boycott the process. The other sign was that the Guardian Council ruled out almost all significant members of the reformist camp from the presidential elections, names like Rōḥānī’s Vice President Ğahāngīrī, or even reformist candidate Hemmatī from only three years ago. Only one less significant reform candidate, hearth surgeon Mas‘ūd Pezeškiyān was left in the race in a gesture that seemed most like a weak gesture. Considering against him Speaker of the Parliament Qālībāf and former nuclear negotiator Sa‘īd Ğalīlī, both trusted and zealously loyal members of the establishment were running. So the real question was whether Qālībāf, or Ğalīlī would take the lead, and if one of the them could win in the first round with an absolute majority. This was further underlined after rumors that one will withdraw favoring the other, after two other conservatives withdrew. But that never came.

And on Friday 28 June results foiled all expectations. Pezeškiyān gained 10.4 million votes, while Ğalīlī 9.4 million, Qālībāf only 3.3 million, and fourth candidate Pūr-Moḥammadī, the only cleric this time just 200 thousand. And that came out at relatively low participation of around 40%, roughly the same as on this year’s legislative elections. And since on that conservatives triumphed and many reformist blocks called for boycotts it is safe to assume that the same electoral core favored Pezeškiyān that much, which is otherwise the establishment’s core support and rather leans towards the conservatives. Thus it is also safe to assume that the reformists now also feeling the chance have significant reserves.

Now what is surprising about the result is not that much the fact that Pezeškiyān could win, and that not even marginally. That has it’s reasons. Much more that it was allowed to happen. On 28 June voting was extended three times, even though the leadership must have sensed that balance is shifting. And despite that results on Saturday came very fast, meaning the establishment was not at all unnerved by this, no efforts were taken to change the image of the outcome.

The other surprising result is that even though Ğalīlī and Qālībāf represent practically the same thing, a very average figure of the nomenclature, the later is more experienced, held more positions is more in the limelight in general, still he performed much worse. They had also run against each other in the 2013 presidential campaign, when Ğalīlī was said to the most endorsed conservative candidate, the personal favorite of Supreme Leader Hāmeneī. Yet that year Ğalīlī not only did not win, President Rōḥānī in a rare achievement won the first round, but came in only third, far behind Qālībāf. And since than he held no major state position, withdrew to a secondary positions to the same party that after 2013 chose Ra’īsī and endorsed him. So it might be that Ğalīlī managed to attract Ra’īsī’s following running from the same party, but in Iran parties are always much less significant than personalities and interpersonal ties.

So it would seem that the one reformist candidate managed to win the first round, and was left in the second with the so far seemingly less popular conservative rival. How he managed to achieve this? Can he win? And what would that bring about?

The key of success

In short, the key of success for Pezeškiyān are two things. His humble stature, and the people around him, his staff.

It might surprise those not familiar with Iran but the elections were preceded by a series of debates, two rounds with all 6 candidates together debating a set of questions, and separately with two aides of their staff debating topics against three experts, almost in a fashion of exam.

During this Pezeškiyān concentrated on very basic messages to mend the basic daily problems of the people, more gestures to religious and ethnic minorities, more relaxed measures with women affairs and a more relaxed Internet control policy. Which hit fresh compared to most of the others focusing on complex ideas. But whenever he faced specific technical questions, especially on the field of foreign policy, he admitted he would let his experts deal with this. And he used the best possible aids, especially in the individual debate, when he appeared with, Rōḥānī’s iconic foreign minister Moḥammad Ğavād Ẓarīf, and also his ambassador to Moscow.

Thus, he perfectly balanced not being particularly known are significant himself, but associating his image with people who are popular, and have already gained achievements. And wishing this campaign images of his great friendship with former president Hātamī appeared more and more.

The popular side of it

Can Pezeškiyān win? That seemed very clear few weeks ago and the answer was no. He was not expected to be in the second round, let alone winning the first. But now that he got through, there are several factors favoring him.

First is that he is somewhat of an outsider. Though he was a Minister of Health, that was twenty years ago, under President Hātamī. And he has been an MP, he held no significant political positions in recent years, largely kept up his medical profession. Meaning that unlike Ğalīlī, he is not specifically a politician, he is a believable professional.

The other factor is that after years of steps against the reform camp there is finally a reform candidate, who could in a very plain language during the debates raise the problems of the ordinary people and gain attention. There were probably less people believing in him before the first round, but now that he got through especially that electoral group that has disappeared since 2013, which chose not to participate, can rally under his banner.

Also there is the lesson of the 2005 elections, when the thus relatively unknown Aḥmadīnežād ran against former president Rafsanğānī in the second round. And though Aḥmadīnežād was not a specifically likely candidate – only gained 20% in the first round – in the second round achieved a landslide victory of 63%. Many voted for him as a sign of mockery, but huge numbers voted specifically against Rafsanğānī, who was that unpopular, while Aḥmadīnežād had his own charm with his sharp criticism and simplistic rhetoric.

The similar factors can very much favor Pezeškiyān now, as the reform camp found a candidate that got into the final round of the race, who could hit a cord with the ordinary people and runs against Ğalīlī, a clear embodiment of state bureaucracy. Which is on historic low popularity now.

Between two hard choices

The Iranian establishment has the tendency to bend the rules, or even the results, though far from that level that is alleged in the West, but now it faces a dilemma what to wish for this Friday, and if it chooses to intervene, which way should do it.

That was very obvious that on the first direct debate between now only Pezeškiyān and Ğalīlī on Monday 1 July the first question was how the two candidates would entice the public to vote and have a higher participation, as both the parliamentary elections and the presidential first round showed only around 40%. Which is record low for Iran. Despite the answers what is important here is that the debates are held in the state channels, so this first concern is much more the question of the leadership, as anything else. And here comes the dilemma.

Letting a reformist candidate with many of the most significant faces of the last four decades of the reform movement – at least those that haven’t become public enemies – on his side, and one very candid about his criticism of the establishment run and win will surely boost participation in the elections. And this helps to heal the inner friction within the state after a series of protests and economic downturns in the last few years. But this will be on the cost discontinuing the track of the Ra’īsī government, inherently admitting its shortcomings, and causing once again a humiliating defeat to one of the “stars” of the establishment. A very uncomfortable scenario for the conservatives, who otherwise now rule the parliament.

The other choice is to do everything possible the make Ğalīlī win and thus Ra’īsī’s work would be continued by a strong member of the late President’s party, a personal protege of the Supreme Leader and Conservative camp would have a solid rule over the state. However, this would further alienate the population from the elections, meaning fours years from now even more embarrassing turnout could be expected undermining the legitimacy of the political system. Which is a key matter now. Both choices have their rationale, yet the interests of the state seem more to favor one outcome more than the other.

And compared like this, yes, it is very likely that no matter how unlikely it seemed two weeks ago, heart surgeon Mas‘ūd Pezeškiyān might just win this election, cutting the conservative cycle unexpectedly short.

Is a great change in the air?

It was very likely that whoever wins this elections will keep most key members of the government in place until the next elections, when a truly new apparatus takes over. That was specifically probable with a conservative president simply continuing what Ra’īsī started. But with a reformist president that will probably change.

In that case many of the key positions will be given to new members. That is why the campaign of Pezeškiyān was effective and telling. On the one hand he kept distance from matters he did not excel, openly saying that these should be left to experts, while on the other hand placated himself with emblematic and successful former cabinet members, like previous foreign minister Ğavād Ẓarīf. Thus indicating the staff that would take over after his victory. With this win turning likely now it is fair to say that most key members of the Rōḥānī government, with some successful staff members of Ra’īsī will take office.

Thus there would be a shift in the foreign policy trying to revive the nuclear deal once again, achieving the nullification, or the circumventing of the sanctions, while not abandoning the achievements of Ra’īsī in the region. Also, as indicated by Pezeškiyān, an internal appeasement campaign will be launched, at least trying to solve most of the social problems with welfare methods and less heavy handed measures.

What makes this scenario likely, and even completely acceptable by the conservative clergy as well, is that now the conservatives have absolute majority in the parliament. It is well acknowledged that the Rōḥānī government had its success, the criticism against were some of the initiatives it took. Which at that time, just like the nuclear deal, was made possible, by support the government had in the parliament that time. That is not the case right now. With the full control of conservatives over the legislation, the government cannot go too far with its policies. And thus this government is acceptable, because it “can be kept under control”.

A victory for Ğalīlī would mean the continuation of the Ra’īsī government, just in a less charismatic manner. While Pezeškiyān’s election would mean a significant, most importantly spiritual change a boost of optimism, even if not overwhelming. Change would not be massive as the conservative parliament would block major, or controversial internal policy changes, and the economic conditions largely due to the sanctions are set. But the change would be good enough to gradually ease the internal pressure and give reforms a chance. Which way Iran goes, it will soon turn out.