If the tragedy and the gradual disintegration in the Arab world discussed last week can be demonstrated in a case of just one country sadly we could mention many ideal examples. Libya, Yemen, Palestine are all in a state where we can surely talk about a distinct geographical and sociocultural entity, but it became very doubtful if there is, or would ever be in the soon foreseeable future a functioning state. Yet, once again sadly, we should not forget these states did not play pivotal role in the inter-Arab politics, and could never aspire to be the leading force behind a supposed common Arabic trajectory. That is why Iraq’s tragedy is much more telling about the history of the last two decades of the Middle East.

Iraq was once one of the strongest Arab states and when Egypt was dismissed from the Arab League it could aspire to fill the vacuum it left behind. In the Iraq-Irani war, though gradually that image faded, it could pose as the supreme Arab power and a uniting one, enjoying the unquestionable support from the Gulf. And though in a very bad way, but undeniably Ṣaddām Ḥussayn became the face of the Middle East for the West. From that once menacing, feared, but respected image Iraq by now became a practical pawn in the neighbors hands. The human toll of this chain of terrible failures in unmeasurable. Since Baghdad started the war in 1980 against Iran, the Iraqi people barely saw peace and anything but progress. This terrible chain of tragedies seem to have come to and end – or a temporal halt – since Dā‘iš was officially defeated in the 9 December 2017, but in the process the Iraqi state almost evaporated. After all, parts of the country has Western – mostly, but not solely – troops on it, while others are under Iranian influence, Kurdistan almost broke away and acquired a large level of autonomy, and Baghdad in the meantime seems to be sunk in a political quagmire. Where is the Iraqi state of Ṣaddām by now?

Since the elections in May 2018, however, it seems a new chapter was started, at least in the Iraqi history after the American aggression in 2003. Since for the first time not only the rulership of those figures whom the Americans put in place in 2003, but the practical monopoly of the once formidable Islamic Da‘wa Party also came to an end. But from that point on, which way Iraq would continue?

The signs are indeed confusing. Shia parties, most of them are outright sectarian triumphed in the last elections and they represent the core of the ruling leadership now, which would indicate a clear Iranian orientation. And there can be no doubt about the Iranian influence. The good cooperation with Damascus, and the strong opposition to further American presence also point to this direction. Yet almost all major Shia coalition leaders, even the famed cleric Muqtadā aṣ-Ṣadr visited Saudi Arabia in the election campaign and Riyadh just recently reopened its consulates in Iraq. A move not fitting at all with a pro-Iranian stance. And while Iraq is visited by the Iranian and the American presidents as well, both of them causing a level of outrage as they where viewed interfering in Iraqi affairs with total disregard for the government, the new Iraqi leadership held high level meetings with Egypt and Jordan recently. So this week we shall take a fair guess where Baghdad is heading, at least where it can. And for that, we have to assess a little what has befallen to Iraq since 2003.

That sad path of deterioration

Truly the Iraq of today bares little resemblance to the once so fearsome Iraq of the ‘80s, which before the war started against Iran was one of the most prosperous states of the region. Rightly so, being such an oil-rich and agriculturally blessed country. But the long war against the revolutionary neighbor not only left behind huge losses in life and infrastructure, but in many other ways as well devastated Iraq. The foreign exchange reserves were depleted completely for the sake of the war effort, which brought no gain, and became hugely indebted. The debt was caused mostly by the heavy borrowing from the small Persian Gulf countries, which were happy to keep the raising revolutionary Iran at bay, but at the end of the war the economic support ended and some, like Kuwait most of all, wanted their money back. Which the economy still in ruins and so dependent on oil revenues plummeted after the oil crises in the ‘70s could not handle, especially with the needs of the huge army built up. Which was one of the prime reasons why Baghdad invaded Kuwait in 1990, to eliminate this debt and gain cash reserves. The adventure, however, failed miserably as the country became even more devastated, and the economic sanctions crippled the state in ‘90s.

Politicly as well, Iraq had a supreme position before the war on Iran, as the strongest member of the Arab League thus far, Egypt was expelled in 1979. Baghdad could have an eye to fill this vacuum and certainly had the ambition for it. Had it managed to score an easy victory against Iran and reassuring a protector position for the Gulf states could have enabled Iraq to really become the leading Arab state and dictate policy in the region. By the end of the war, however, Egypt steadily regained its positions and that lead to its readmission in 1989 to the Arab League. The war on Kuwait further alienated its Arab neighbors and made it a pariah not only in the international stage, but even in the Middle East.

The internal cohesion of the state also suffered greatly by that two failed wars. The ‘60s and the ‘70s were full of Kurdish separatists activity, but the creation on a Kurdish autonomy in 1970 – with no real local power, serving more as a symbolic step – and the cut for foreign – mostly Iranian – support for the separatists made Baghdad more in control of its northern regions. The Ba‘at policy with all its shortcomings had indeed managed to provide a distinct Iraqi national identity above sectarian fault lines. The war on Iran, however, partially due the revolutionary policies of the Islamic Republic broke that somewhat superficial Iraqi national cohesion. First in sectarian lines as big parts of the southern Shia population had clear sympathy for the new Islamic Republic, and later on ethnic grounds as Iranians once again supported Kurdish separatists. The chain of Kurdish uprisings lead to the infamous Operation al-Anfāl by the Iraqi Army at the later stages of the war and was marked by the infamous Ḥalabğa massacre in 1988 by chemical weapons. The war on Kuwait and the American invasion in 1991 also had a great affect on the Kurdish case. The UNSC resolution 688 reaffirmed the Kurdish autonomy, for which the US gave protection by imposing a no-fly zone. The Iraqi Army pulled out of the area in 1991, leaving it practically in the hands of the two grand Kurdish parties. Economic conditions and infighting, however, left that part of Iraq not in any better state, only in a deep animosity for Baghdad.

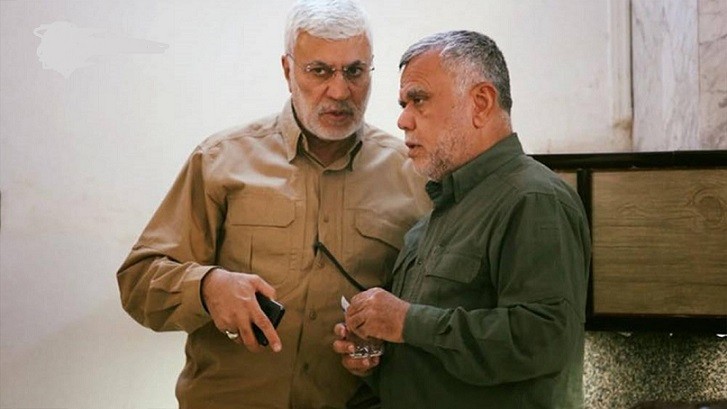

The Shia question was, however, not any less pressing. The main Shia political movement was the Islamic Da‘wa Party, founded in 1958, which was for a long time lead by one of its founding members, Grand Ayatollah Muḥammad Baqir aṣ-Ṣadr. His nephew, Muqtadā is now one of the most influential Iraqi politicians. The Da‘wa Party was vocal in its opposition to the Ba‘at government, but the real problem came with the Islamic Revolution in Iran, for which and for its leader the party expressed sympathy and open support. The execution of Baqir aṣ-Ṣadr in 1980 and the abolition of the party pushed its supporters to harsher policy and a number of them forming the Badr Brigades. These joined the Iranian Army in the war along many other smaller groups. These were known collectively as Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq (SCIRI), in which the remnants of the Da‘wa Party and the Badr Brigades played the most significant role and were armed and trained by the Iranian Revolutionary Guards (Pāsdārān). Two of its leading field commanders, Hādī al-‘Āmirī and Abū Mahdī al-Muhandis also became leading political figures in Iraq in the recent years.

Leaders of the Popular Mobilization: Hādī al-‘Āmirī and Abū Mahdī al-Muhandis

The years after 1991 were even more catastrophic for the Iraqis as the war years before as for the economic sanctions the GDP fell drastically and living conditions became almost unbearable. Even worse, Iraq became surrounded by hostile states all around. Syria was regarded as an enemy ever since Ṣaddām officially took over, after almost successful negotiations of union between the two Ba‘at governments. And Damascus indeed openly helped Iran in the war. Iran was naturally hostile, and even managed to recover from the war faster than Iraq. Turkey, as a natural enemy and a NATO member was not any friendlier. The Gulf states, so friendly in the war were scared of Ṣaddām after 1991 and hated his state. The southern and northern parts were under American air supervision and the Kurdistan region fell out of control. In this state Iraq was just lingering on. Economic recovery and political rapprochement with Syria – offering to buy Iraqi oil and sell in in the global markets – only stated after 2000, when American invasion came in 2003. The Americans and their allies not only caused huge destruction, but the occupation and the interim government, the Coalition Provisional Authority lead by Paul Bremer completely dismantled the former state, and privatized the economy.

Soon enough insurgency started against the invasion, which gave way to internal fightings as well, plunging Iraq to unseen instability and lack of safety. As Islamist terrorists were pouring into the country, those Shia groups came home as well, which were persecuted by the previous government and thirsted for revenge. This opened the darkest chapter in Iraqi history so far, which was marked by a constant insurgency against the occupation, but also by sectarian infighting. Which the occupying Western forces let loose viewed as an opportunity to ease the burden upon themselves as militants were busy finishing each other off. The situation only started to improve somewhat by 2009-2010, when the new Iraqi government managed to reach American pullout in 2011, at least officially. But Baghdad had little time to enjoy this free hand, as late that year the so called Arab Spring kicked in and soon enough reached neighboring Syria. Iraq, contrary to the expectations did not join the proxy war on Syria, waged by the Western and the Gulf governments, and along with its own interests tried to provide as much support as it could. That policy upset many supporters of the war on Syria and they raised the pressure on Iraq as well. As documents prove by now[1], the same forces laid down plans for the disintegration of Iraq, and in 2014 Dā‘iš started its bloody march. By January they took control of al-Fallūğa and ar-Ramādī, practically most of al-Anbār province along the Syrian border, and at that time Washington rushed to make it clear it will not provide any assistance against this menacing threat. In May the country saw the first relatively free and fair elections, the first one after the Americans officially pulled out, and as the results were still fresh Dā‘iš stormed and took over Mosul, the country’s second biggest city. The Iraqi Army at that point practically fell apart and as Dā‘iš started to push towards south the Iraqis desperately needed help. That came from Iran, which helped to organize the Popular Mobilization (al-Ḥašd aš-Ša‘abī), in which the same al-‘Āmirī and Muhandis played the major role, who were once fighting on the side of Iran, and who now took good use of their relations with the Pāsdārān. That mobilizations helped to turn the tie and eventually liberate the country. The American lead coalition came only after the Popular Mobilization stopped Dā‘iš and had a more negative affect by that time, than it claims or what it could have provided in the beginning of 2014, when Dā‘iš was still in embryonic stage. When the war ended in 2017 the country literally became in ruins, though that being over with and the situation significantly improved in neighboring Syria Baghdad can finally have an eye for the future. But which way to go from here?

The political baggage

The biggest problem of a fresh start is the still heavy political burden from the previous eras. Both before and after the American invasion in 2003. Also the political fault lines even within the Shia power groups, which collectively came to dominate the political landscape.

One of the old problems is the heritage of the Ba‘at Party, which was once seen as could be solved with a single blow to the former structure. This party, however, was much more that a political movement before 2003. As Iraq was a one-party state, practically the whole state apparatus and the army belonged to the party. Not as much for conviction, but for opportunities and livelihood. The Paul Bremer lead Coalition Provisional Authority initiated a de-Ba‘atification process, which meant that anyone who belonged to the party was discharged and barred from ever joining state service. And that happened even before the new state structure was properly set up. That meant the total dismantlement of the state and the army. In the state level that meant that all administrative positions had to be filled with people without previous experience. More destructive was the dismemberment of the army as not only thousands of professional soldiers were poured to the streets, but hundreds of well trained high ranking officers were left without a job. While they had to witness the return of the same Shia groups, which they were fighting in the ‘80s, and as sectarian infighting got unleashed. Some of them joined the ranks of the forming Sunni rebel groups, which were fighting the American invaders, but also the Shia militias, and their lines were swelled by the thousands of jihadis also pouring into the country. That was the hotbed for Dā‘iš later on, for which one the main components were former Ba‘at officers, like ‘Izzat Ibrāhīm ad-Dūrī, Vice Chairman of the Iraqi Revolutionary Command Council lead by Ṣaddām Ḥussayn, and one of his most trusted advisors, who came to lead the Naqšbandī Army based on a Sufi order. Since many of he former Ba‘āt members themselves Sunnis took shelter in a religious identity. That alone proves the total collapse of the former Iraqi national identity since those building it and struggling the hardest for a secular state dropped this mentality and adopted a religious identity, which they despised before.

The influence of this Sunni circle was formidable despite all attempts. In the North around Mosul and al-Anbār they were in practical control even before the Dā‘iš onslaught and they openly scorned the government in Baghdad. Some prominent Sunni families, like the an-Nuğayfī, however, also supported this current. The head of the family, Usāma an-Nuğayfī became a minister in the Transitional Government in 2005, then after the 2010 elections became Speaker of the Council of Representatives until mid-2014. His younger brother Atīl was the governor of Nineveh Province between 2009 and 2015. He was not only mainly responsible for the fall of Mosul to Dā‘iš, but it is likely that he cut a deal even before with Turkey and Saudi Arabia to carve out a Sunni state in the north for themselves. Right after the fall of Mosul he formed his own militia, for which he got the biggest support from Turkey and vowed to liberate the province himself. Yet, right at that time, when the Iraqi government issued an arrest warrant against him he held excellent ties with reappearing American troops as well. He was only acquitted from treason charges by the parliamentary commission thanks to his brother being a member of it. The fact that he is still not in prison despite all attempts, and his brother was elected to Vice President in 2016 proves well that even though Iraqi politics became ruled by Shia parties the major Sunni components of the society could not have been nor eliminated nor satisfied. If these factors and the thousands of former Iraqi armed officers are not appeased Dā‘iš in one form or another can easily resurface. This fear only grows in Iraq as for almost a year now the US is transporting arrested Dā‘iš members from Syria to Iraq, and their faith over there is rather obscure. And these grievances, just like it happened with the al-Nuğayfīs, can be a part of outer attempts for the partition of Iraq.

The Kurdistan region also poses a serious threat to the integrity of the state, regardless of the failed attempt to gain independence by a referendum. The Iraqi state barely exists in Iraqi Kurdistan, which is already operating almost as an independent state. But the biggest concern is the huge Israeli lobby, which now supports Kurdistan and its bid for independence. That, added to the fact the politics in Baghdad and the reshaped Iraqi armed forces based on the National Mobilization Units are very close to Tehran might result in a proxy war within Iraq. But even if that is not to happen, it surely poses a liability for Iranian strategic thinking towards Iraq and the future of the region.

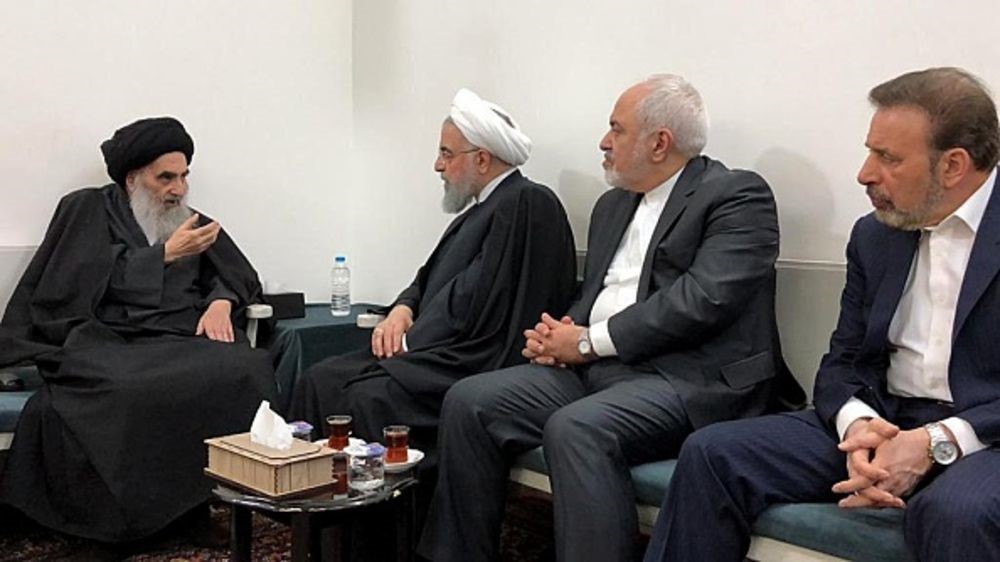

These, however, are “just” regional, provincial problems, which a strong political will in Baghdad could overcome, or could form a way to live with. The real question is, however, where Baghdad is heading. And here comes the problem of the disunity within the Shia. While it is true that there are hundreds of parties in Iraq since 2003 even within the Shia, that is why most of the parties don’t run individually but collectively in joint lists, there are three distinct power centers among them, all with their peculiarities. Unlike the Sunna, the Shia Islam is somewhat structured in a hierarchical basis with Grand Ayatollahs at the top. Iraq currently has only one Grand Ayatollah, ‘Alī as-Sīstānī, who resides in the holy city of an-Nağaf and outranks all other senior Shia scholar.

With a huge amount of religious endowments and schools under his guidance he is immensely influential. He, just like his predecessor and former master Grand Ayatollah Abū l-Qāsim al-Hū’ī, who even the wartime years against Iran set down with Ṣaddām Ḥussayn for a tv interview are known for his moderation. This approach did not support the Shia uprisings in the ‘80s, nor those against the Americans and as-Sīstānī himself regularly urged Iraqis to take part in politics and elections. Even though he himself usually refrains from taking part directly in political decisions. He, however, just like his master, is from Iranian decent and only moved to Iraq. That being seen by many as a weak stop on his resume and he is known to have good relations with Iran, he never promoted an Iranian style state structure in Iraq. He tries to distance himself from the image of being a man of Tehran, as even last time Iranian President visited an-Nağaf in March 2019, he avoided a lengthy meeting. By most he is viewed as a conciliatory force, who regularly urged calm and restraint from violence.

The other major religious authority is Ayatollah Muqtadā aṣ-Ṣadr, nephew of late Grand Ayatollah Muḥammad Baqir aṣ-Ṣadr, who was one of the founders of the Da‘wa Party. His father was also an influential Grand Ayatollah. He is Iraqi from an-Nağaf itself and has control over a huge force known as the Mahdī Army made of supporters of his clan. Muqtadā himself much younger than as-Sīstānī had a much sharper attitude both towards the Americans and the Sunni jihadis as he lead a revolt against the American invasion in 2004. His views are much closer to a conservative religious state, much like Iran, but he never favored a strong Iranian patronage. Since 2003 Muqtadā eagerly tried to gain prominence both by fighting the Americans and politically through his Ṣadrī Movement (at-Tayyār aṣ-Ṣadrī). His party is party is the biggest within a larger coalition, the as-Sā’irūn (Forward)[2]. His family has a huge reputation just like he himself as both his father and uncle were Grand Ayatollahs, though he himself is not. There is a natural competition between the two major scholars in a number of matters, which is fueled by Muqatadā’s annoyance with as-Sīstānī not only over ranking but also by denying him the role of a holy warrior like his uncle was. As for Iran, he is considered as the Shia force farthest apart from Tehran as he usually resented Iranian influence in his country. He recently aired his concerns that the recent feud between Tehran and Washington might bring Iraq into the conflict, which he viewed not permissible.

The third biggest Shia power center, however, is not based on the religious authorities, but on the Popular Mobilization lead by Hādī al-‘Āmirī and Abū Mahdī al-Muhandis. They enjoy the biggest support from Iran as they themselves fought with the Iranian army back at the day, and the Iranians trained and armed the Popular Mobilization against Dā‘iš. Therefore they have immense popularity for achieving victory, but at the same time feared by many as being just extended arms of Tehran, and viciously violent themselves.

Since the Americans officially handed over politics to the Iraqis in 2004 the Da‘wa Party ruled in one form or the other, longest served by Nūrī al-Mālikī at the helm. That era, however, is not only marked by violence from sectarian infighting and uprisings against the Americans to the war with Dā‘iš, but also by massive mismanagement of state funds and impossible levels of corrupt inefficiency. Which was perfectly symbolized by the rapid collapse of the army and state after the fall of Mosul, only to be saved by competing outer forces. That state management was only saved by Ḥaydar al-‘Abādī, an other Da‘wa member, who served briefly as Minister of Communication in 2003, but largely withdrew from daily politics until he became the replacement for al-Mālikī in the summer of 2014. He was indeed a much more efficient and capable, also much more modest leader, than his predecessor. But as the huge mistakes before 2015 practically destroyed the Da‘wa Party, he himself departed and building on his government’s relative successes formed his own movement, the Victory Coalition. The main questions in the 2018 parliamentary elections was who would benefit from the disappearance of the Da‘wa, who could claim the benefit of victory over Dā‘iš, and just how close the new government would end up to Tehran.

Elections and choices

The elections, relatively peaceful and clean to the local standards was won by the as-Sā’rūn, though only 54 seats out of the 329. The next two, only slightly behind were the Fatḥ Coalition – practically the Popular Mobilization – and the Victory Coalition lead by al-‘Abādī, who still had hopes for continuation. Muqatadā was swift to announce his victory and his will to form a government. The long coalition negotiations were mostly fruitless as neither of the two major block – those lead by aṣ-Ṣadr and al-‘Abādī respectively – could claim majority. The result came in October as ‘Ādil ‘Abd al-Mahdī, a former Da‘wa member and Vice President between 2006 and 2011 was chose by the president to form a government, who is by now is viewed as independent as there is no major party directly behind him. This move was the best possible compromise to create an efficient technical government mostly free of the blame of the former ones.

With such a constellation, where neither aṣ-Ṣadr nor the Hādī al-‘Āmirī lead Popular Mobilization units are completely happy comes the question which trajectory will such a compromise government take? As we saw in the recent months Baghdad both had gestures to Riyadh, Amman and Cairo, while holding on to the strong bond with Damascus and Tehran. In his recent visit to Tehran ‘Abd al-Mahdī made it clear that Iranian support is pivotal. So he is in a very difficult position.

Internally, he has to rebuild the country and maintain a balance both between the regions and the capital, and between the feuding Shia parties formally behind him. Which is strictly connected to regional equation as the militias behind Hādī al-‘Āmirī are eager to pick a fight with the Americans and to take full control of the areas along the Syrian border. Both to prevent Dā‘iš from reappearing, and to further consolidate the Syrian-Iraqi-Iranian block. Their fears from are not unfounded, since while the HRW talks about arrested terrorist being transported by the Americans from Syria, other sources suggest planed relocation of armed fighters. Which would fit with a strategy by Washington to prevent such regional block such way, since Dā‘iš is largely viewed in the region as an American proxy army. Whether such plan exists or not, it is imperative for the new Iraqi government to stop the American presence since that can trigger an infighting and might indeed sink the country in yet another war if conflict breaks out between Tehran and Washington. The relations with Riyadh are just as important, since as we saw in the election campaign the Saudis are now once again wresting their influence and talk about rapprochement. That might not be desirable for many, but as Mosul proved it in 2014, leaving Riyadh unhappy can have catastrophic consequences. There is little doubt that Baghdad, at least for the time being, will stay close to Tehran. That cannot be evaded nor economically, nor politically. But if this tenure will indeed witness the total disappearance of the Da‘wa and those who dominated the last 14 years, with the grow of new parties there might be new realities in the political spectrum. Which is, at least internally much needed, if partition is to be avoided and some form independent Iraqi decision making is to be restored.

[1] Asrār suqūt al-Mawṣil [Secrets of the Fall of Mosul, Twenty pieces documentary series by dr. Muḥammad Al-Kāẓim], Afāq, Aired from 11 November 2015 to 24 April 2016

[2] Which is ironically made up by a number of secular and smaller Shia parties, and even the Iraqi Communist Party.