Since December 2018 Sudan was boiling. That is unfortunately nothing special for the decades since independence in 1965 have often been volatile in this vast country, which is a peculiar middle ground between Sub-Saharan Africa and the Arab World. Even the last three decades often witnessed instability from coups to inter wars in the south and in Dārfūr, even though the same leadership managed to hold on to power since 1989. Thus the government of ‘Umar al-Bašīr seemed to be unshakable despite all calamities. This illustrious former general, who once served in the Egyptian Army in the 1973 war with Israel survived links with Usāma bin Lādin, the Dārfūr war, decades of civil war in the south, which lead to the partition of the country, warlike feuds with neighboring Chad and Libya, several coup attempts and the arrest of almost all of his former aids even managed to set a world record by being the first ever active head of state being under arrest warrant by the International Criminal Court (ICC). He so far managed to dance his way out of all troubles, as was his hobby at the end of every rally, but despite his truly amazing tactical skills, cunning and the undeniable general economic progress in his tenure, the last few years witnessed such economic and social crisis that people took to the streets in December. Which lead to his deposal and arrest on 11 April by the army. He left as he came, but the people did not leave the streets and the meltdown of his leadership still continues to this day. We were hesitant to cover this story for two main reasons. Firstly, because the events seem to go on and we don’t see nor the end, nor the real major reasons behind al-Bašīr’s fall. And the Arab press seems so far seems quite apathetic to the news, as if nothing extraordinarily happened. Secondly, because Sudan is such a vast and multiethnic country, in many ways relatively detached from the general Arab events, that it can be quite a puzzle sometimes.

So in this week we look into Sudan. How this world recorder president left? What is his legacy? What are the secrets behind his downfall? Who are the people taking charge now? And what are the possible scenarios for the future with all the possible impacts to region?

Once largest Arabic country

Until the partition and the birth of South Sudan in 2011 with its 2,5 million km2 territory Sudan was the biggest Arab country, and with the roughly 52 million people the second most populous after Egypt. However, this still vast country is a complex jigsaw of some 70 languages and ethnic groups from Arabs, Berbers and various African peoples. While it is true that the Arabic language and culture play the dominant part, all other components of the society added to its flavor creating something unique. But that explains why Sudan, though closest tied to its Arab neighbors still somewhat detached from the major Arab currents.

The country only gained its independence in 1956, greatly by the result of the Egyptian revolution in 1952, but the previous 150 years were marked by Egyptian and British rule. Between 1899 and the independence it was formally ruled jointly by Egypt and the UK, which explains the why so many Sudanese leaders – like al-Bašīr himself – studied and started their careers in Egypt. The terribly impoverished country was swinging back and forth between Islamic revivalism and leftist ideologies from one coup to the other, and falling to one extreme of Marxism to the other with Islamist social experiments. The mainly agricultural country only started to see significant development in the ‘70s with more export oriented agricultural production, which often added to the clashes between the south and the center and between city and the countryside. That was the same time when oil was first found in Sudan in big quantities and the export begin, mostly in the hands of Western interests, like Chevron. Which created a constellation not peculiar to Sudan, where economic interests tie the country to the West, while its political class is trying to distance itself from it. The development brought social progress as well, often disregarded or downplayed, yet remarkable. By the late 2000s, however, a new supporter turned up, China, which invested heavily. This resulted a Chinese economic presence in Sudan, often described as one of the worst possible forms of Chines economic exploitation. This growing rivalry of influence in Sudan, along with the sanctions due to ties to Usāma bin Lādin and the internal wars increased the pressure and in 2011 the south broke away. Against which Khartoum had not much to do. In recent years, however, the regional value of Sudan grew rapidly due to its strategic position and formidable army.

Sudan sits in a truly strategic point. First of all has control over a large section of the Nile, which is a vital interest for Egypt. It is halfway between Egypt, the southern exit of the Red Sea, and Saudi Arabia, right next to Yemen, and Libya. Therefore both the events in Libya and Egypt since 2011 were of special interest for Khartoum, and the Saudi aggression in Yemen, for which it lended troops. But as the struggle between the Qatar-Turkey axis and the Saudi-Emirati-Egyptian block spiraled out the price of Sudan increased. That is why many are eager to see which way Khartoum shifts, if that to happen at all. Therefore Sudan is at the crossroads of struggles both between global and regional actors.

The ideological and social composition is also peculiar in Sudan, and has huge weight in any evaluation. Ethnically the population is a delicate mixture of Arab, Berber and African populations, where the tribal relations – often intermarried – play significant role. These, just like the regional components of the country have to be respected, and any government has to keep a fragile balance. Islamic thinking is dominant in the country, which is hardly a surprise, since the Sudan in the eighteenth century was the home of the Mahdī[1] movement, which by ousting the British for some time created a religious state. That might fell, but had a huge legacy in a country, where both jihadist feelings – against neighboring Christian Ethiopia – and Sufism was for long deep rooted. Later on, due to the proximity to Saudi Arabia and Egypt both Wahhābī doctrines and those of the Islamic Brotherhood gained significant footholds. So Islamic thinking in one way or another runs deep in the Sudan and is well imbedded in a largely tribal society. Despite that, due to British influence cosmopolitan mentality was not unknown in the big trading cities along the Nile. Therefore leftists ideas were popular, and that explains why the Sudanese Communist Party in its heyday in the ‘70s – though still limited in social support – was the biggest in the Arab world.

This pattern gives a case where any government has to be a careful mixture respecting tribal, ethnic and regional sensitivities, or has to rely on the army to keep the country under firm control.

The last three decades

When the army took control in 1989 in a bloodless coup the new administration was an interesting marriage between the army and the Brotherhood. It is generally true that in the post-colonial Arab world Leftist progressive ideologies and Islamic movements were entangled in a struggle for the future, which was marked by military coups in hand and Islamist uprisings or governments on the other. Therefore either Islamic movements took hold based on the masses, or the army build on – sometimes quite artificial – progressive doctrines. Only in rare cases we see marriage between the two. Sudan is one of these rare cases, since the coup in 1989 was by and large planned and organized by the National Islamic Front (NIF) – the local branch of the Brotherhood -, only executed by a handful of army sympathizers. The real leader behind the move was the head of NIF, Ḥasan at-Turābī. In his 2016 interviews to the Qatari state channel al-Jazeera – known for its links to the Brotherhood – accounted that they themselves cherrypicked the leaders of the coup, and he even got to know the

eventual leader, ‘Umar al-Bašīr a day prior. Since at that time he was nothing extraordinarily. Based on his views the steps taken resembled the closest to the Iranian Islamic Revolution. But unlike in Iran, where the whole new state was build around the religious institutions, in Sudan the leading religious movement utilized the already existing army with al-Bašīr at the helm. The newly set up Revolutionary Command Council for National Salvation (RCC) introduced an Islamic civil and penal code, banned political parties, placed all power formally into the hands of al-Bašīr as head of state, government and the armed forces, yet withheld real decision making to a small consultative assembly formed by NIF members. So, the army took power, but at the head of a massive popular movement and formally under Islamist logo.

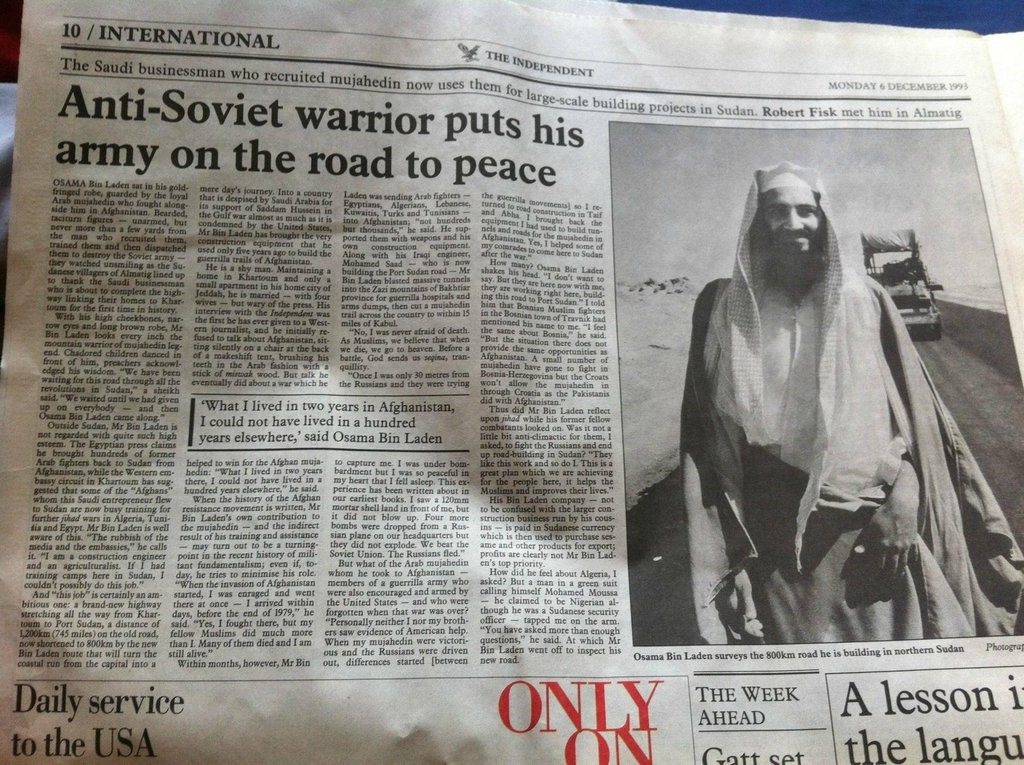

Al-Bašīr, however, proved to be much more resourceful as anticipated and in 1993 by disbanding the RCC he appointed himself to be President, than started to sideline most NIF members. The main source of conflict between the two arose from the difference that while al-Bašīr was alway a practical and skillful man, at-Turābī was an idealist. And while a theoretician can afford to experiment on the implementation of principals, a real head of state has to make compromises. Like it happened with the ill-fated monetary reform, where the Sudanese pound was dropped for the creation of the Sudanese dinar, only to be dropped a few years later and to reintroduce the pound, but in a much inflated rate. At-Turābī also pushed state support for a number of armed movements usually at odds with the West, and created a collective called Popular Arab and Islamic Congress, where a large number of armed organizations were invited. Though some of them, like Carlos the Jackal was nor an Arab nor a Muslim. Most prominent among these was Usāma bin Lādin, who even moved to Sudan around 1991. That sounds bad today, but at the time he was far from the dreaded character the world came to know after 2011. Quite the contrary, even by the Western press at the time he was a “Saudi businessman” and “anti-Soviet warrior” for his deeds in Afghanistan with Saudi money and American support. Therefor such moves were, at least until a point, acceptable for both sides. But after the first World Trade Center terror attack in 1993 Sudan was put under sanctions for supporting and hosting terrorist groups. That antagonized the already bad relations with neighboring Libya and Egypt, which were hard supporters of the previous Sudanese governments.

From 1996 on, probably due to the general elections held that year, in which al-Bašīr finally became elected president, Sudan started to oust most of the radical elements invited before. Also started to ease relations in most directions and started to invite foreign – mostly Chinese by that time – investments again. The fallout between the two leaders was inevitable as in 1999 at-Turābī got arrested and put into prison for the first time, because he tried to forbid the president to run in the next elections. Al-Bašīr finally took the hold firmly into his own hand, and got re-elected in 2000, but he had little time to rest. Only a few years after sanctions for sheltering radical groups, and the destruction of the aš-Šifā’ pharmaceutical factory by the Americans in 1998, believing it falsely to be a chemical weapons factory al-Bašīr only got rid of his partners heritage, when tensions started rose up rapidly in Dārfūr.

The Dārfūr war from 2003 was a prime example of broken ethnic balance in a region, where foreign hands intervened. The land already home of a dozen ethnic groups was divided between sedentary – mostly non-Arab – and pastoral – mostly Arab – communities. When in worse climatic years the usual tension heated up, the quarrel soon got an ethnic edge, and soon enough with the help and money of the Libyan state that time – though Tripoli was not alone in this – an armed rebellion was on the way. Khartoum responded with force, though mostly in fear of international criticism and internal sensitivities, it relied mostly on local Arab armed groups and volunteers. The war was brutal and prolonged, estimates range from 10-20,000 to 200,000, by the time an initial peace plan was signed in 2006. The area got regional autonomy, but in the 2016 spring referendum Dārfūr chose to stay part of Sudan and somewhat rebuild central control. Dārfūr is indeed the scene of al-Bašīr’s biggest losses and victories as well. The chaos and the war caused such international attention that brought Sudan even worse reputation than the ‘90 with at-Turābī, and because of that on charges of genocide the ICC issued arrest warrant against him in 2008. Which is still standing. It was a worrisome issue than, but eventually got forgotten and by 2009 al-Bašīr visited international forums. The real success lies here, that managed to survive the conflict and only after five years the south broke away – after decades of much worse civil war – Dārfūr chose to stay. Thought this had much to do with the fact that after 2011 the biggest, though far not the only supporter of the rebels, al-Qaddāfī’s Libya was no more. For that, as act of sweet revenge, al-Bašīr even took credit claiming he armed the rebels.

The big return

After Dārfūr was calming down and the south broke away, Sudan was hit surprisingly little by the so called “Arab Spring”, and by that time Khartoum was gaining position, at least in the Arab world. Which is remarkable, since from the

start the al-Bašīr–at-Turābī tandem was betting on very wrong horses. Sudan was the only Arab country to openly support Iraq in 1991 as it invaded Kuwait. For decades Khartoum was at odds with Libya, Egypt and the Gulf, with very few supporters as Sudan was backing very radical elements. By 2011, however, al-Bašīr very tactically supported the Gulf executed operation, otherwise know as Arab Spring. First as a revenge on Libya, than as a realignment with Egypt. As Khartoum welcomed both the Brotherhood government lead by Mursī, both the coup deposing him lead by as-Sīsī. By his words in the 2015 Egypt Economic Development Conference it was obvious Khartoum is on the Egypt-Gulf block’s side in regional disputes. Despite the remarkable economic growth, especially in the ‘90s and 2000’s[2], which regularly makes Sudan one of the fastest growing economy in Africa, it was still relatively isolated country by the US sanctions. The Gulf support practically broke that blockade. The price was Sudan’s involvement in the Saudi aggression against Yemen in exchange of $2,2 billion, since Riyadh desperately needed forces on the ground with real fighting capabilities. Soon after the two sides signed four economic agreements, which opened the door for massive Saudi-Emirati financial support. It seemed al-Bašīr outwitted all obstacles. He came back to the Middle Eastern scene after long isolation, survived decades of outer interference and the so called Arab Spring, managed to produce remarkable economic growth with some tangible social impact, circumvented both ICC arrest warrants and American sanctions and even managed to put an end to two separatist conflicts. At the same time he got ever firmer grip on the government based on the military by ousting the Brotherhood, still holding on to an Islamic appeal, at least formally and in stile. Truly remarkable tactical skills.

Unfortunately for al-Bašīr, what managed to bring him back to scene hastened his downfall. The operation in Yemen was always meant to be a low-profile matter as it was hugely unpopular and the troops by 2018 openly demanded withdrawal. Though the number of the active forces involved is still

relatively unknown, by 2017 it was admitted that they lost 412 troops including a number of officers, which puts them to the second biggest casualty rate after Saudi Arabia. While that was a push factor in its own, the outer reason, which made al-Bašīr to think about Yemen twice was the inter-Gulf conflict since the summer of 2017. Sudan carefully evaded to join the blockade against Qatar, only tacitly expressed support, and never really took a side. It seemed the ties between Khartoum and Riyadh are unshakable, but in 2017 al-Bašīr accepted a significant offer from Turkey. For a period of 30 years Turkey leases the island of Suwākin on the Red Sea, a once formidable, but by now largely abandoned trade port in a strategic position, for the remarkably cheap price of $650 million. For that money, which was largely assumed to come from Qatar, Turkey was given sovereignty over the island and the right to build a military base there. This move made both the Egyptian and Saudis nervous, but regardless all pressuring attempts Khartoum stayed adamant. Thought it is interesting that 2016, so not much before the agreement, is the time when sudden Brotherhood interests renewed in Sudan. That is time of the lengthy interviews by al-Jazeera and many other stations with at-Turābī.

The downfall

Suwākin was, especially now looking back, was probably the first wrong step. Then on 16 December 2018 al-Bašīr travelled to Damascus to meet with Syrian President Baššār al-Asad. He was the first major Arab head of state to visit Damascus since 2011. Since both the historical and the current economic-diplomatic relations are weak between the sides, al-Bašīr was clearly delivering a message to the Syrian government that Riyadh is ready to negotiate. It is only more probable, since it came only more than a week before the Emirates reopened their embassy in Damascus. Though that quite well demonstrates the status al-Bašīr held in the eyes of the Saudis, he was still a relatively neutral middleman to deliver the massage. Yet as soon he returned, massive demonstrations started in practically all major cities. While the official reason was the increase in the fuel as alimentary prices it was hard to evade the connection between the trip and protests. Which even though gained momentum, seemed to be manageable as al-Bašīr in 9 January called for his last major rally. In that he still managed to point the finger on foreign interests to destabilize the country – which was probably not unfounded – and played well on the Islamist strings, since that was officially still an Islamic oriented government. But that came to be the last time he could dance in front of the public, as the protests started to grow. In these women played a significant role, which really got the attention of the Western press. That might immediately sound suspicious as yet another Western cheesy operation to cause unrest, and indeed the protests were much bloodier then assumed, women in Sudan are actually well integrated into the public life. And as many example show, the level of their appreciation is admirable even by Western standards.

On 11 April 2019 the armed forces took over, arrested al-Bašīr, who was put under house arrest, and a Transitional Military Council (TMC) was formed headed by Aḥmad ‘Awḍ bin ‘Awf. ‘Awf was only made first Vice President late February in an attempt to consolidate support from the army, as he was Minister of Defence since 2015. Largely responsible for the Yemen operations he was one of al-Bašīr’s strongest allies. Only three days before the coup ‘Awf in an public announcement took al-Bašīr’s stance as foreign interests were trying to exploit the situation and warned that the army will protect the government. And before anyone worried what house arrest meant for al-Bašīr, he should take confront that he was to live in the 2015 built new presidential palace, which puts most five star hotels to shame. Whatever made ‘Awf turn sides clearly did not last long, since he resigned only a day later. On 16 April the Military Council replaced the Vice President and his Deputy and by 20 the coup against against the coup was complete. The new leadership announced to start negotiations with the leaders of the protesters and on 13 May agreed on a settlement, to have a two years transitional period and return the power to a civilian government after elections, but it is noteworthy that TMC already announced the source of legal power is already and has to be the Islamic law.

The change in faces and approaches

The the coup within the coup had to take place, since the first move on 11 was only a replacement by the same ruling elite. The new head of the TMC is ‘Abd al-Fattāḥ al-Burhān, a relatively low profile, but respected general. Real power, however, clearly wrests at his deputy, Muḥammad Ḥamdān Daqalū, only known by his nickname Ḥamīdtī. What is known about him is that he was dropped out of school by the age 15 and than became a caravan escort and camel trader – a practical bandit -, who never held any civil or military post until 2014, when he became a army officer. That is due to his services in Dārfūr, where he organized a 40 thousand strong militia on the side of the government and his services were handy ever since. As probably even now, he controls a large force both within the army and outside of it. Though he was never particularly close to al-Bašīr, who was actually moved on 17 April to the infamous Kobar prison. Ḥamīdtī’s real power and supporters are well apparent as only this week, on the 24 May arrived to Jeddah to hold talks with Saudi Crown Prince Muḥammad ibn Salmān. The two sides reaffirmed each other from continued support, which was clear even during the second phase of the coup, as on 21 April Riyadh and Abū Zabī promised to loan $3 billion to Sudan and transfer some $500 as a “friendly gesture” to the Sudanese Central Bank. Out of that some $250 million already arrived from Saudi. That would suggest that Riyadh and Abū Zabī supported the ouster of the long time president, who was their ally and only recently made them a service.

There can be two possible scenarios and both are connected to the inter-Gulf war, which is going on for two years now. In that the Suwākin Island and the Yemeni war mission has significant role. Either the Turkish-Qatari axis supported the push in retaliation of al-Bašīr’s mission and to prevent a Saudi-Syrian rapprochement, or the Saudis started the move to replace him with a closer ally as he failed in his mission. But either way, during the transition the Saudis invested more, which in understandable given the weight of these matters. The first achievement was revealed on 26 April, when the Turkish foreign ministry denied rumors that the Sudanese TMC revoked the Suwākin agreement. Which is more likely a face saving attempt to salvage at least the prestige, since that means a very significant strategic plan ends up in the bin with all the money invested in it lost. Which is only a matter of time to turn out to be true, and will for the great satisfaction of Riyadh. But now Muḥammad ibn Salmān needs support for his Yemeni war, maybe more than ever, since it was his mission from the very beginning and by now a rupture appeared with his father over the matter, who is rumored to might replace him. That was even confirmed by the Emirates. Only in the last moth three major secret delegations went to Sudan – one Emirati, one joint Saudi-Emirati, and one Saudi -, which might even indicate a new chapter in the growing rivalry between Riyadh and Abū Zabī. The last of these was on 19 May, so less than a week before Ḥamīdtī’s trip to Saudi, lead by Hālid ibn Salmān, Deputy Defense Minister and brother of the Crown Prince, ahead of a large security delegation.

Either way it happened two things seem to be certain. Al-Bašīr’s long tenure might be over, but he will likely escape extradition to the ICC, since the new government wouldn’t like embarrassment and the Gulf sponsors simply don’t care. The other is that by now Sudan seems to be firmly under Saudi-Emirati control and even if there would be a quarrel between them the Turkish-Qatari attempt to a military base is thwarted.

What is quite significant, however, is the relative silence upon the news by the regional, and the almost total disregard by the Western media. After all, where are the 24/7 coverages like in Egypt 2011? That such a figure like ‘Umar al-Bašīr would fall is clearly not ruling the headlines. And there is a reason for it. Whatever happens, Chinese economic presence in Sudan is indisputable and regardless the events they will make the economy going by all expectations. The people might protest today, but the new military junta already chose the next president, who has his foreign sponsors, his own militia and by the Islamist moves of the TMC, his own at-Turābī, who is yet to be seen. So realistic change is father than it seems.

[1] The term in Islam means the savior, who would return at the end of times. Though many instances are known, when people claimed to be such, Islamic history only remembers two occasions, when this gained massive popular support. Both, the al-Muwaḥiddūn in thirteen century Morocco, and in this case in the Sudan resulted in formidable states.

[2] Both the growing potential and the fact that it is mostly due to foreign investments shows, by the fact that by current expectations Sudan even in 2019 will experience a 5,1% GDP growth. Despite the current turmoil.