Indeed the Arab world is surrounded by myths and generalization, both in the West and in the Middle East. In the West someone hears about the Arab world might remember a few stereotypical terms, like Islam, aggression, uncertainty, Arab Spring, disunity and even terrorism. That is the general negative image. There is also another, more positive, but somewhat romanticized image of dunes, camels, exotic buildings and culture, even a great level of modesty. The new image, thought only about the Gulf, intermixed with the romanticized idea, is a modern, oil built society, with an openness to the West with a strong connection to religion and tradition. Some of these images are very much alive in the Middle East, but in a light that most of these negative or stereotypical images exist because of foreign effects on the Arab world, which especially in the last two centuries suffered so much colonialism.

Some of these images are to a certain degree might even be through, but in fact the Arab world has as many faces as countries, if no more. There is one country, which fit many of these ideas, still it is a country like none other. Little does the world know that one day there was an Arabic colonial power, which was one day rivaled the Portuguese Empire. Which was in fact so powerful that managed to hold on to much of its colonial possessions even in the twentieth century. That is Oman, which has very intense connections with all its neighbors, not just the Arabs, yet takes almost no role in the eternal regional fights. A country, which became immensely rich by the oil, but that did not change it so fundamentally as it is so characteristic in the Gulf. A country, which is Muslim, yet has a long fraternal tradition with other religions and represent a form of Islam, most books regard disappeared for centuries. That country is Oman, which in the height of its power had so great influence on East Africa and the Indian Ocean that many modern country became attached to the Arab world by it. Oman is a unique, yet in many ways so typical Arab country, it worths the attention. These peculiar notions shall be our topic this week, so we shall see how colorful can the Arab world be in some occasions.

Between land and sea. A unique approach.

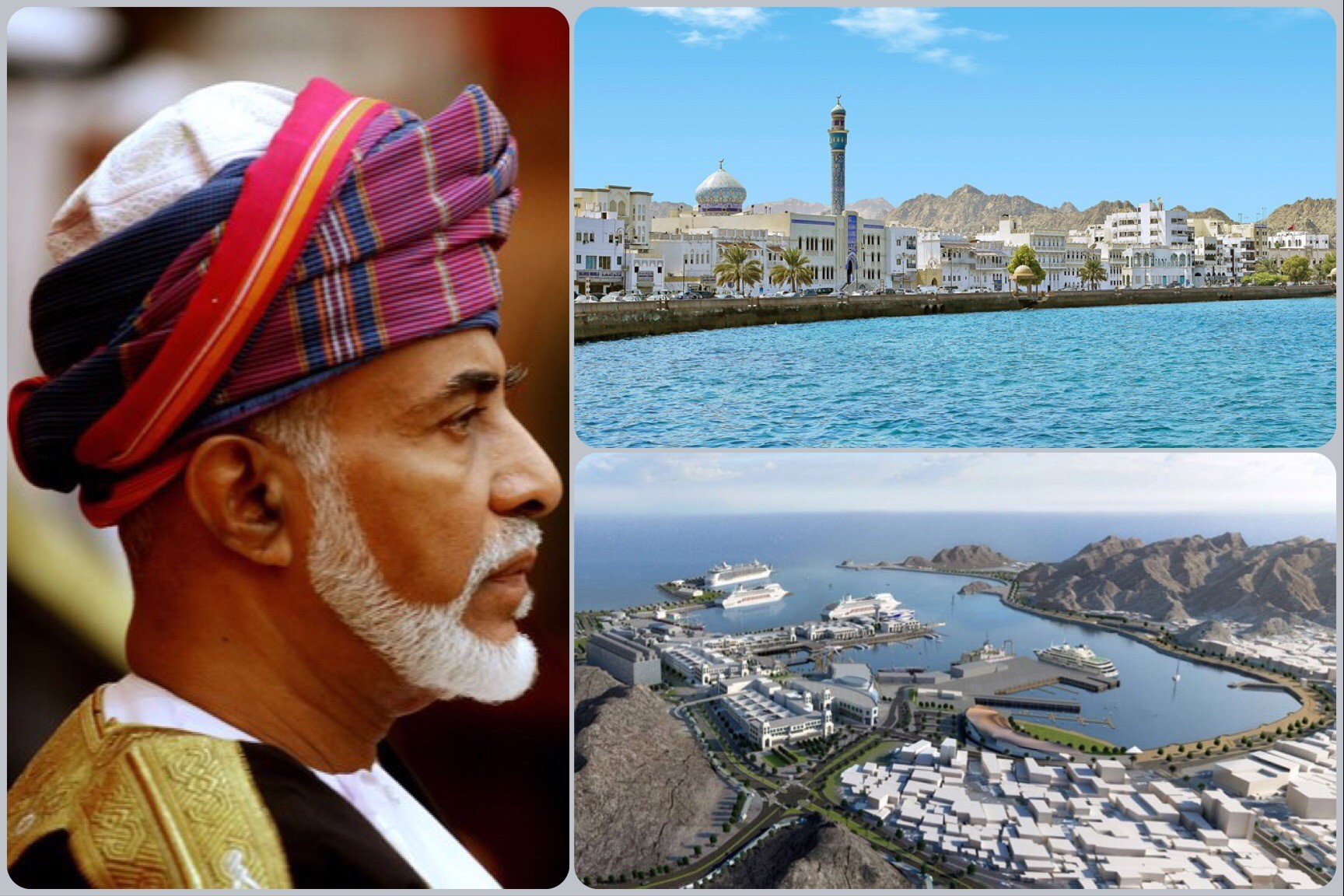

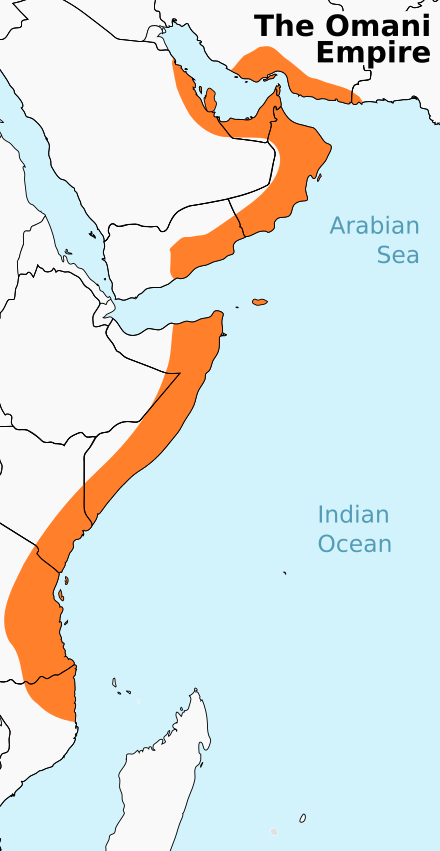

The modern Oman sits of the shores of the Indian Ocean, in the southern tip of the Arabian Peninsula, just like Yemen. It also has a little exclave on the tip of the Musandam Peninsula, not only connecting it to the Persian Gulf, but also making it part of the Strait of Hormuz, having a control over one of the most important oil trade routes of the world. Unlike Yemen, however, Oman was always less attached to the events of the Arabian Peninsula, but much more to the Indian Ocean. Therefore since the beginnings of time it had intense connections to India and East Africa. Sea trade, which is usually less connected to the Arabs, was always an integral part of the Omani life, so it is less surprising that by the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries it had possessions both in modern India and Pakistan, while also in East Africa.

Partially by these experiences Omanis were always more opened to the outer world than most Gulf Arabs, though almost had no connections to the West up to our modern age, therefore there is a view about Oman that it is an isolated part of the Arab world. What image lives in the Arab mind as well, since Oman was always much less interested by the currents of the Middle Eastern events. But there are two other aspects to this cultural richness. One comes from abroad, as Oman was many times part of major empires, which wrested their control over this land, both from the West and the East. The other is that indigenous inhabitants of this land are not entirely Arabs themselves. The old Southern Arab culture, a distant relative of the Arabs, once predominant in Yemen and Oman, thrived in this land and formed the first cultures even in the Sumerian and Akkadian times. Most of the Southern Arab languages and the cultural presence dissolved in the Arab masses, but some of it, like the Mehrī language, stayed alive here, contributing to a cultural distinctness. Though by the fourth or fifth century Arab tribes moved in and inhabited the inner parts of Oman, this heterogeneity, together with the seafaring tradition, is something unique to Oman. This passed on the Arab language and culture to many places around the Indian Ocean, and Islam even beyond that. Which should be remembered, because unlike the most remembered Islamic conquests, this was a peaceful transmission of the religion. And that emanates from Oman’s religious life.

Sunni or Shia? None of them.

One thinks about the Middle East, Islam, or the Arab world, it is inescapable to mention religion and put up stereotypes from Sunnis, Shiis and the great divide between them. However, Oman is a country, which for long stayed out of this dispute. Because they are in fact not really any of these big categories.

Most introductory books about Islam only mention the two main branches of Islam, the majority Sunna, and the minority Shia. More detailed books describe the numerous branches of the Shia, or might even the so many Sufi orders. Only history works talk about a third branch, which once existed, the Hāriğī group, which is usually viewed all, but extinct. But not in Oman, where in the form of ‘Ibādī Islam, it not only survived, but became the predominant denomination.

The story all goes back to the first century of Islam. After the death of Prophet Muḥammad the followers, the halīfas came to lead the new Muslim community and state. The first four were elected and they are called collectively as ar-Rāšidūn, the “Rightly guided ones”. Though at first the most likely candidate after the Prophet was his cousin, ‘Alī ibn Abī Ṭālib, he was only the fourth one to be elected, some twenty four years after the death of Muḥammad. Yet by his time the initially small Muslim community and state became a vast empire, and his rise to power caused the first internal war in Islam. Those, who were staunch supporters of ‘Alī became his party, šī‘at ‘Alī, in tine formed the Shia, while those stood against him in time became the mainstream, the Sunna. The two most prominent members of the party fighting against ‘Alī were the Syrian governor at the time, Mu‘āwiya ibn Abī Sufyān, and the Egyptian governor, ‘Amīr ibn al-‘Āṣ. As ‘Alī rallied the troops to squash these rebellious local governors, the first battle took place at Ṣiffīn, in modern day Syria at 657. Though the battle was indecisive, ‘Alī accepted mediation to prevent further bloodshed. That, however, caused major slip in his own ranks, as many viewed that it was impermissible for the chosen of God to negotiate his rule, and if he did, he is no longer worthy of support. That group left his camp, moved out, which gave them the collective name Hāriğiyyūn, meaning those, who moved out. They soon came to renounce both major camps and develop their own doctrine of collective rule and the election of ruler by collective decision. They were so keen to stop the internal split and return to the days of the Prophet that they planned to assassinate all three major leaders of the time, ‘Alī, Mu‘āwiya and ‘Amr, yet only managed to kill ‘Alī. Their utopian dream, however, prevented their unity and soon scattered to distant domains of the Islamic world, which was also the result that most viewed them as nonconformists and heretics even.

In small pockets, like in the middle of Algeria, they survived to this very day, but in the large scale they indeed soon disappeared. But not in Oman, where they found sanctuary, and soon caused this country to depart on a unique Arab-Muslim history, largely detached from the main currents. Because in 751 the local ‘Ibāḍī imams rose up against the Abbasid caliphs and formed a rule of their own.

Modern day ‘Ibāḍīs strongly denounce that they would belong to the Hāriğī branch, nowadays rather classifying themselves as either conservative Muslims, or unique Sunnis. Yet they admit that their movement rose from the troublesome days of the third and the fourth caliphs, when the Hāriğī doctrine were formed, which longed for a return to the egalitarian days of the Prophet. While the more radical elements fought hard against almost any central rules and renounced all other Muslims as infidels, the more moderate groups, like the ‘Ibāḍīs refrained from this and lived in smaller pocket communes in the southern parts of the Arabian Peninsula in relative peace. In the last years of the Umayya Caliphate (660-750) the ‘Ibāḍīs attempted a revolt in the Ḥiğāz and Yemen, which was dealt with, but by the time it would have been put down the central authority was so weak that a for a short time an agreement was reached between the Umayya forces and the ‘Ibāḍīs in expense of the more radical local groups. That, however, soon ended and the ‘Ibāḍīs were expelled to Oman. That is the same time in 750, when the Umayya dynasty fell, and the Abbasids took over. A year later the ‘Ibāḍī community, renouncing not only the major dynasties, but both the Sunni and Shii approach to leadership, elected its first own imam. Though in time state rulership was formulated, the elective and conciliatory nature of the ‘Ibāḍīs stayed to this very day, which is noticeable even in the Oman state. From this humble, and largely isolated situation the ‘Ibāḍīs soon spread out in the Indian Ocean, but also held smaller communes in the Sahel and the relatively isolated domaines of North Africa.

Living in their relative isolation from the main currents of the Middle East, and being broken away before the Sunni-Shia strife gained a real depth, they read both branches’ works, but developed their own doctrine. But they also soon broke away from the main currents of the Hāriğī movement as well, which made them a highly conservative and puritanical group, adopting ideas from both main branches, but having a unique flavor of their own. This puritanical approach made them highly receptive and tolerant to other religions, which was further aided in Oman by the frequent experiences of other people due to regular sea trade.

Pawn of empires becoming an empire

Though being an important trade junction between different sea faring cultures and having been influenced by Ethiopia and the ancient South Arabian cultures, the two most important cultural impacts came from the inner lands of the Arabian Peninsula and Iran. From the desert region Arab tribes migrated in, a phenomenon going on until the nineteenth century, and settled in the inner lands of the modern Oman. The Iranian influence was strong both in the Achaemenid and Sassanian periods on the coast, and these Empires kept a strong presence until the Islamic conquest. That dichotomy is not a unique feature of in the Persian Gulf, where the inner parts are more tribal, while the coastal territories are more outward for the sea. The same can be noticed in the history of Kuwait, Qatar or the modern UAE, but in the case of Oman it was more significant, given its size. And this duality had far bigger consequences.

The Islamic conquest happened relatively smoothly and a decade after the death of the Prophet became final. As we saw Oman soon broke away from the Abbasid Empire, but with its gradual demise Oman suffered from the uncertainties in the Gulf. The last of these influences came by the Seljuk Empire, which though Oman even briefly gained some presence in southern India and the Pakistani coastline. A dual system ruled Oman, which stayed a peculiar characteristic until our present day. While the coastal area came under the rule of neighboring empires, the inner lands were lead by the imams elected by ‘Ibāḍī scholars. In 1154 the Banū Nabhān (1154-1624) managed to push out foreign presence and secure their own rule as kings. That was the state rulership, under which the the moral leadership of the imams stayed on. The Nabānī kings, whose capital was in the mountainous inner lands became rich from the frankincense trade and by trade secured possessions in East Africa and in the islands of the Indian Ocean, creating a strong Omani state. That was ended by the Portuguese conquest, which first took control of Muscat in 1507 and gradually expanded its presence in the whole coastal area, even in Iran. That was further complicated by Ottoman incursions, which twice took control, though only temporary, Muscat and much of the coast. In the early seventeenth century the Nabhān dynasty rose once again, but was put down by the a new dynasty, the Ya‘rub imams (1624-1742). Under their time the imams once again became the prominent rulers of Oman. Taking back the coast from the Portuguese, they created the strong maritime empire from their capital,

Muscat, which saw the main adversary in the Portuguese. With gradual fights they took control most of the East African coastline. That is the time they came to strongly secure their hold on Mozambique and Zanzibar, which became the centerpieces of the Omani Empire. That is also the time they held control over the Comoros, which has its strong cultural effect there up to our days, as the Comoros view themselves Arabs and now they are members of the Arab League. That was the beginning of the lucrative slave trade from Africa, for which the center was Zanzibar and the Zanğ coast. Since that time the African became known in Arabic as zinğī, mostly meaning African slave.

The Ya‘rubī state fell apart in the middle of the eighteenths century due infightings between the inner lands and the coast and by Persian Ṣafawī interventions to these troubles. From these struggles at the end the Bū Sa‘īdī, or simply Sa‘īdī dynasty came to power, both as imams and sultans until our present days. The Sa‘īdī state kept on being rich by the slave trade, due to its possession in Zanzibar. But it was also marked by regular infightings due to the elective nature of the Omani leadership. Many times sultans were put down by contenders supported by the tribes of the inner lands, sometimes gaining power back built on the power of the dominions. In one of these fights Omanis by chance gained control over the port of Ġwādar in the Pakistani coast, which they held until 1958, though the Omani rulers had a limited sovereignty over the port for even longer.

By the middle of the nineteenth century Great Britain became the strongest power in the region, and when it abolished the slave trade the formerly rich Omani Empire started to diminish. In 1861, after intervening in a succession struggle the British divided the Oman to the Sultanate of Zanzibar (1861-1896), a British protectorate, and the Sultanate of Muscat and Oman, which in 1970 became the modern Sultanate of Oman. Interestingly the former relation did not break for long, and Zanzibar payed an annual tribute to Oman until 1967.

Oman became an effective British protectorate, an informal British colony, which was crystallized in the Treaty of Sīb in 1920. That granted large authority to the Imamate in the interior and gave power over the the coast to the Sultanate. All that guaranteed by the British. The treats fell apart in 1954, when oil was discovered in the inner domains, which the British wished to exploit, and for which a more direct control was needed for the Sultan. In the five years war for authority Muscat was aided by the British and Iran, resulting a direct central control. This was shaken once again in the ‘60s, when in an uprising started in the province of Ẓufār, the formerly richest Omani territory due to its frankincense richness. The movement, supported by leftist parties and governments in the Arab world – mostly North-Yemen – wished to overthrow all monarchies connected to colonial powers. In 1970 in a bloodless cue the son of the Sultan, Sultan Qābūs took over, who rules Oman up to its present day. With help from Britain, Iran and Jordan he put down the rebellion by 1975, and he rapidly changed the state.

A rapid modernization was started with British help, in many ways similar to what happened in the Gulf, mostly based on the oil income. However, unlike the monarchies of the Gulf, and in large part due to the ‘Ibāḍī tradition of puritanical approach, Oman was not transformed culturally and did not became a slave market of foreign laborers. The other peculiar feature of Sultan Qābūs’ state was that Oman, again, unlike the other Gulf states, kept a strong connection with Britain, and never really switched to the American dominance. Which allowed Oman to stay away from most of the modern Middle Eastern struggles, even though it built strong relations with the Gulf states.

Friends for all, foe for none. Omani foreign relations.

Under Sultan Qābūs Oman sacrificed a lot for modernization and soon opened up for tourism. But at the same time the puritanical nature of the Omanis never changed, thanks to the limited and well controlled tourism and quality education. By IMF estimates in 2018, Oman was to be expected the fastest developing state is the GCC in 2019, meaning ahead of the UAE, or Qatar.

Nonetheless, Qābūs viewed it imperative to engage in an active, but peaceful foreign policy. Oman supported the independence of the small gulf monarchies in 1971 and became a founding member of the GCC in 1981, being the second strongest pillar in the alliance after Saudi Arabia. For Oman the rational was economic and political cooperation, but not to the expense of a free hand in foreign policy and not for involvement in larger struggles in the Arab world. As the GCC started to gain a more forward foreign policy Oman started to slowly distance itself, though never leaving, which manifested in many ways. During the Iraq-Iran war in the ‘80s Oman refrained from direct confrontation with Iran, which later payed off as an honest broker of later peace initiatives. Oman always stayed away from the Saudi-Emirati quests against Iran, or for larger influence in the Arab world during the so called Arab Spring. For instance, Muscat never severed relations with Damascus during the Syrian war, and its Minister for Foreign Affairs[1], Yusaf ibn ‘Alawī visited Syria three times during the war.

Oman was also the secret intermediary between Iran and the West, and the formal negotiator in the final stages up to the JCPOA in the 2015. That soon payed off well for Muscat, as soon after the Iranian nuclear deal, when the Iranian market was only just opening up and the restoration of official financial channels were still only in sight Oman gained a gas deal with Tehran. The initial agreement was reached in 2013,

so even before the JCPOA and was finalized in 2018. By this deal Oman would build an underwater pipeline and would import daily 15 billion cubic feet of Iranian gas. The project is reported to be in its final phases and would launch sometime in 2020. Oman is in fact not in desperate need of Iranian gas, as it is well supplied by Qatar already, but by creating a gate to Iranian trade, would gain a serious leverage over Tehran,

, which might as well serve as a security guarantee in case of larger regional conflict. It is hardly a coincidence that in the July 2019, when the tension rose high in the Gulf between Iran and the West, by mutually confiscating trade freighters from the other side and war seemed only inches away, it was Yusaf ibn ‘Alawī, who rushed to meet the Iranians. So right when the most prominent members of the GCC did their best to provoke a fight with Iran, Oman did exactly the opposite, and thought not asked for it by Tehran, mediated for its sake.

Oman is also noticeably worried of the Saudi policies in the region. When the Saudi-Emirate blockade started against Qatar in 2017 Oman not only chose to be neutral, as the initial Kuwaiti conciliation failed, but even strengthened its economic ties with Doha. In March 2019 Yusaf ibn ‘Alawī caused a smaller shock as he openly took the side of Qatar, saying the blockade is not a solution and Oman will try to salvage as much from the GCC as possible.

That was not the first time, however, when Oman openly defied Riyadh. When Saudi Arabia started its war in Yemen, Oman was the only GCC member, which did not join the campaign, regardless the common defence pact. Both in 2015 and in 2018 Oman hosted talks between the different Yemeni factions, and there were even reports that in certain times, as gesture of good will for further negotiations, Muscat allowed al-Ḥūtī fighters to be treated in Oman.

This conciliatory policy, however, many times caused uproars in the Arab world, mostly by Oman’s similar mild policy towards Israel. When the “deal of the century” was a top priority in the region, the same Yusaf ibn ‘Alawī caused a smaller scandal in April 2019 in the World Economic Forum, saying: “I believe that we Arabs must be able to look into this issue and try to ease those fears that Israel has through initiatives and real deals between us and Israel.” Though he strongly refused that this should mean recognition to Israel by the Arab states, and he pointed out that no solution can be achieved without the Palestinians, and without withdrawal from the occupied territories. A typical symptom of Arab inner politics that while Oman does not formerly recognizes Israel, it has strong and open connections with it, those Arab states attacked Muscat the strongest, which does the same, but secretly. But while Oman has connections, even sometimes suspiciously close ones, like having meetings between Sultan Qābūs and Netanyahu in Muscat, it always refrained from deeper cooperation. Not like the Saudis, who were just recently caught conspiring with the Israel to assassinate Iran’s most legendary general, Qāsem Soleymānī.

This ambiguity in Omani foreign policy can be understood both by Omani history and a strict rationality. Oman lays relatively far from the most problematic parts of the Arab world, except Yemen, and has little influence. Its traditional isolation from the Middle East lead it to be conciliatory for its own benefit. Which proved to be fruitful in many ways. Oman has no traditional enemies in the region, and gained the best out of most intermediary attempts. Doing the opposite, what Qatar did, which strongly misjudged its capabilities, and that can have severe consequences in this turbulent region.

Tradition and transition.

Sultan Qābūs, being in power since 1970, making him the longest serving Arab leader, has no heir. Thought the Basic Law – serving as a constitution – does not even allow him to name one, built on the elective ‘Ibāḍī tradition, in a royal degree in 2017 he appointed As‘ad ibn Ṭāriq, his cousin as deputy PM, practically making him his successor. That would put power in the hands of another branch of the dynasty, given the clergy will approve it.

This limitation seem to be strange, or even unbelievable, since Oman is an absolute monarchy. The power of the religious elite indeed rests upon the tradition and the customs, not as much on the written laws. The sultan is the head of all three powers, as he appointed the judges and presided over the whole legal system, he is the head of government, Minister of Finance and Foreign Affairs and even head of the National Bank. When Qābūs took control there was no representative body, and even slavery was only abolished in 1970. Then gradually a bicameral National Assembly was created. In 1981 current lower house, the Consultative Assembly, and in 1997 the current upper house, the Council of the State. The later was the result of the Basic Law in 1996, which thought serves as a constitution it only regulates some aspects of the political life, and in no way limits the sultan’s powers as absolute monarch. The sultan can issue royal degree by wish, and has huge power over the National Assembly. Parties are banned, and in the lower house representatives are elected directly. But the results can be altered by the sultan, he chooses the speaker, and the the elections have no direct connection with the government. The upper house is made up entirely by the sultan, and has to pass any law coming from the lower house. Above all this, however, the sultan is in constant contact with the elite and governance is carefully negotiated. The whole system, even with the occasional economic problems, like in the last few years by the sudden drop of oil prices, seem to operate smoothly and was only put through one major stress test.

In 2011 the so called Arab Spring had its overspill here as well, but the main reasons were mostly economic. The main demands were more jobs and higher wages, and as these were reached, the tension started to cool. The Basic Law was changed to give more power to the Consultative Assembly, but the penal code was also altered to better curb protests. Though with its reported 2-6 deaths and a few injuries it seems to be minor, the 2011 and 2015 election were major concerns for the leadership. Only after 2015 a gradual change started to take effect, as the sultan, though unofficially but finally elected his heir, and gave more freedom to the elected bodies. With the new rules the first parliamentary elections will be held in 27 October 2019, with an expected huge turnout.

Oman is indeed a unique Arab state. Harnessing the deepest Arab and ancient Southern Arab traditions. It has a rich thalassocratic and colonial history, many times being in equal terms with the Western powers of the age, but in time became consumed by the British. It has a highly collective, somewhat even democratic Islamic tradition as far as rulership, for which it many times played a huge price, still the only absolute monarchy in the Middle East apart from Saudi Arabia. It has a history like none other, an Islam like none other, a such peaceful and profitable foreign policy, again, like none other. It managed to survive the loss of its colonies, being a colony itself, though officially always stayed independent, and the great transformation by the oil wealth. All that with staying still one of the most isolated and conservative, yet least criticized Arab country.

All that hopefully stays much the same after Sultan Qābūs passes on power. That is yet to be seen, but for the new times the new elections in this very month, might be the entry.

[1] Though the effective Foreign Minister is Yusaf ibn ‘Alawī, his title is State Minister for Foreign Affairs, as the Foreign Minister is the Sultan himself.